Q&A: USC’s Morgan Polikoff on new poll data & the ‘purple classroom’

Beth Hawkins | April 11, 2024

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

A recent poll from a pair of University of Southern California researchers found broad agreement among Americans about the value of public education but partisan divides regarding what schools should teach and at what grade levels. Respondents also favor parental rights as a concept but don’t appear to have considered the practical aspects of how schools should approach exempting individual students from particular lessons.

A recent poll from a pair of University of Southern California researchers found broad agreement among Americans about the value of public education but partisan divides regarding what schools should teach and at what grade levels. Respondents also favor parental rights as a concept but don’t appear to have considered the practical aspects of how schools should approach exempting individual students from particular lessons.

The top takeaways mirror what Anna Saavedra and Morgan Polikoff found in a 2022 survey that confirmed the ideological divide fueling the so-called culture wars — but also revealed widespread uncertainty about what students are exposed to in school. Wanting to better understand this seeming disconnect, in September and October 2023 the pair asked a nationally representative sample of 4,000 households to respond to dozens of hypothetical in-class scenarios involving race, LGBTQ topics and opt-out requests. They then correlated the answers with respondents’ more general beliefs about education.

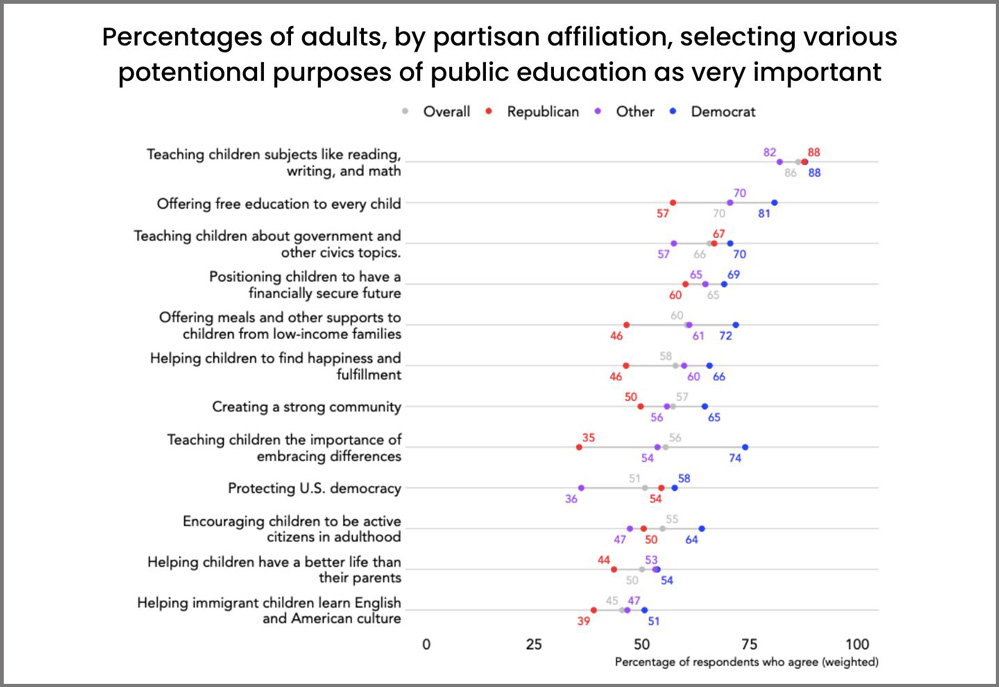

Nearly 9 in 10 of those surveyed say teaching basic academics is a very important purpose of public education, with smaller pluralities agreeing that protecting democracy, teaching about government and civics, and providing a free education are priorities for schools. Three-fourths prefer spending to improve the quality of public education over paying for low-income children to attend private schools.

From there, however, ideological gaps begin to appear. Teaching children the importance of embracing differences, for example, was very important to 74% of Democrats versus 35% of Republicans. And while 9 in 10 respondents want children taught to treat people equally regardless of skin color, just 14% of Republicans say it is all right to assign a lesson on U.S. policies benefiting white Americans, versus 46% of Democrats.

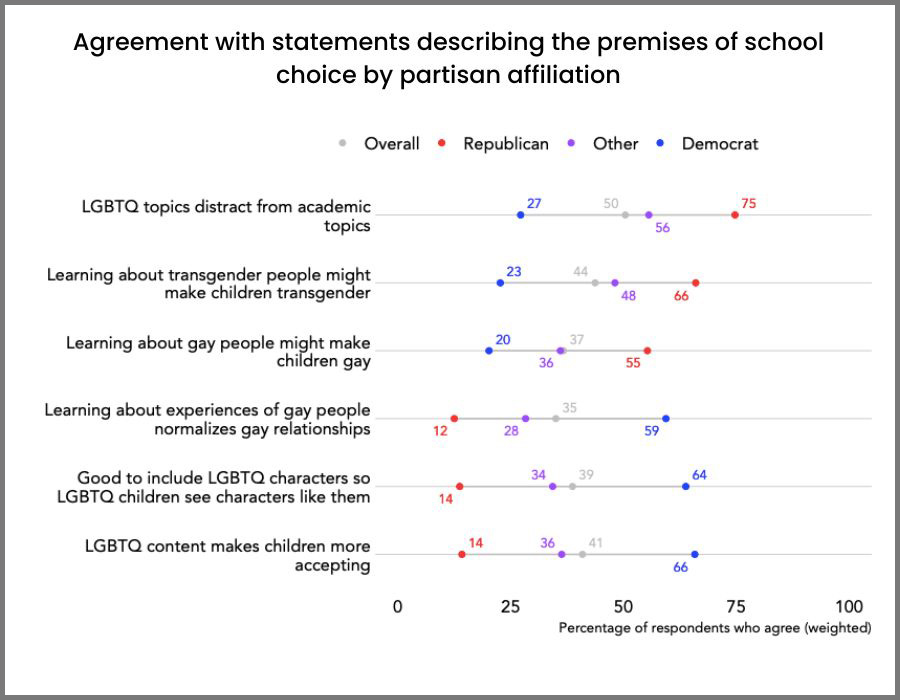

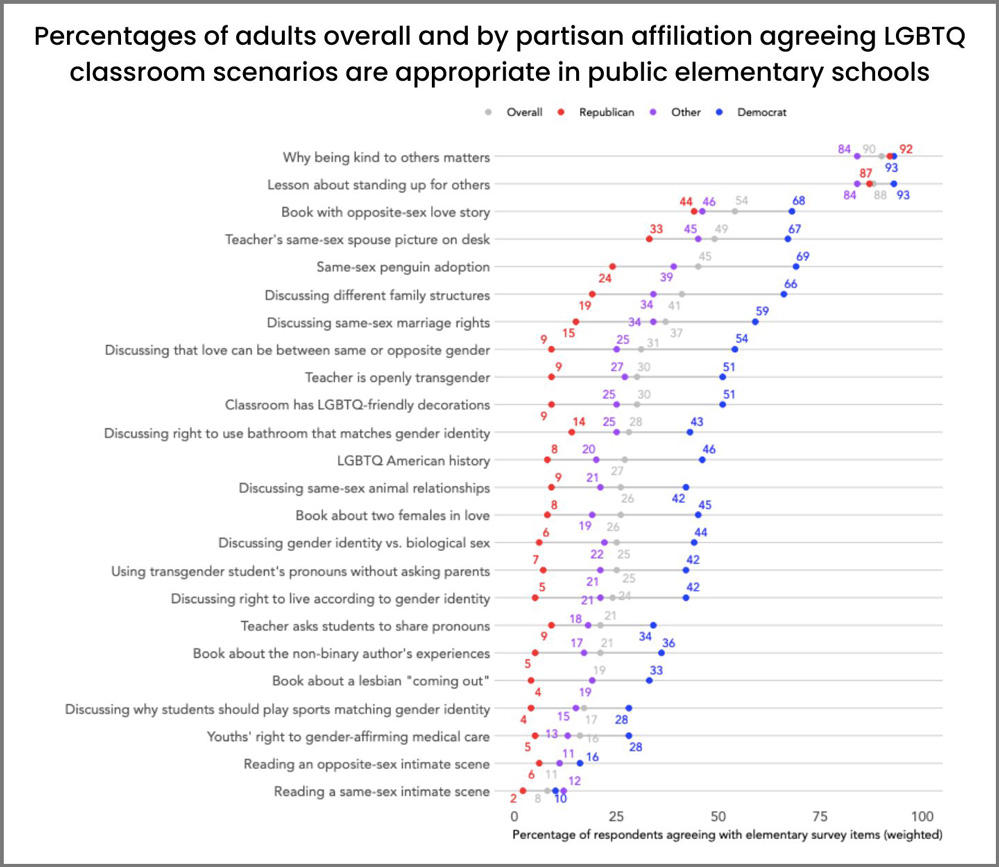

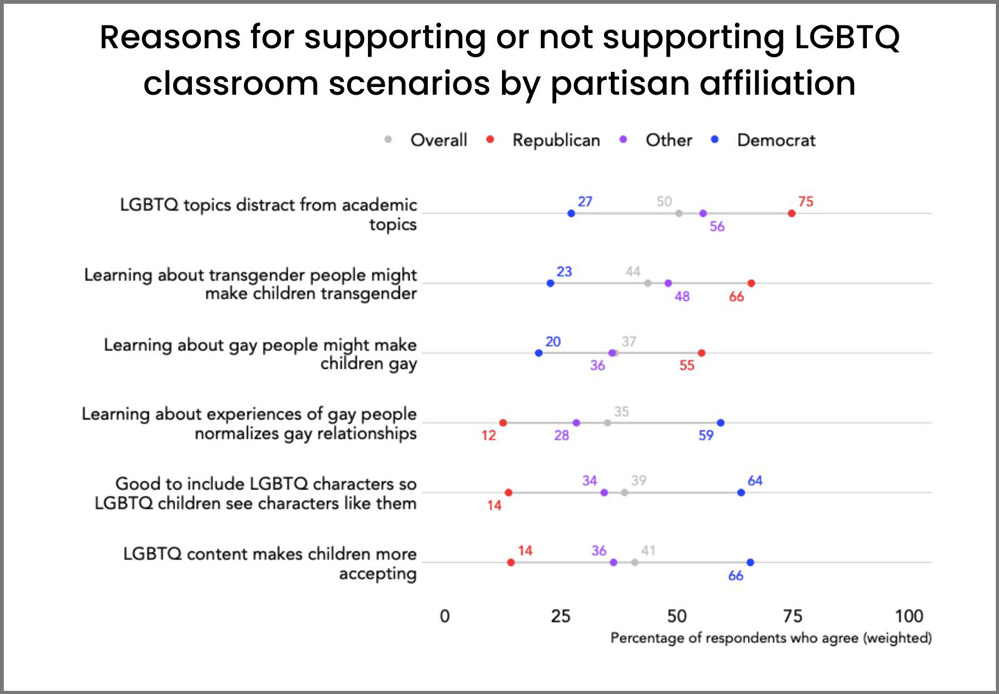

The biggest partisan differences involve LGBTQ topics. Most Democrats — 80% to 86%, depending on the scenario presented — support instruction in high school, a rate that falls to 40% to 50% in lower grades. Republicans, by contrast, are comfortable with LGBTQ topics less than 40% of the time at the high school level and less than 10% in elementary school.

The bottom line, Polikoff said in a recent interview, is that in order to find a path forward, Americans need to have more detailed conversations about what children should learn, why and when.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

I’m curious why you started your report with information about people’s support for education.

We really felt people’s views on the purposes of education do shape their answers to all the more detailed and specific policy questions. For instance, we asked a first broad question about the purposes of education, gave people a bunch of options for answering and asked them to rank their top three.

It’s obvious but not obvious. The top finding when you ask these kinds of questions is almost always something about the basics of teaching children reading, writing and math. Most people, when they think of school, that is what they think of first.

But by and large, we didn’t see lots of partisan differences, except on one item of teaching children the importance of embracing differences. When we looked at the relationships between the purposes and people’s ratings on other items, we saw that that question was the most predictive.

You found fewer divides on market forces and choice in education than one might expect, with widespread preferences for spending public money on public schools, 4 in 10 saying competition makes public schools better and a slim majority agreeing that it pushes them to make better use of resources. Why is the partisan gap less stark on these issues?

The average voter doesn’t know very much about education policy. For Republican politicians or people who are in the Republican ecosystem, school choice is their education issue. It has been for a long time, but it really is now. For the rank-and-file voter, it’s not all that salient.

On average, Republicans are somewhat more supportive of choice policies, but those gaps are not really that large because I think lots of Democrats support some of these principles, too. The idea that if your neighborhood public school is no good that you should be forced to stay there forever — it’s not a very appealing argument. And then there are lots of Republicans who like their local public schools and believe in public schools. It just doesn’t cleave very neatly, the way, you know, feelings about trans people do.

That’s a tidy segue. You used scenarios to tee up detailed questions about what, specifically, should be taught about race and LGBTQ people. Why?

In 2022, when we asked questions about LGBTQ topics in the curriculum, we asked very general questions: Should schools teach about sexual orientation? Should they teach about gender identity? But the real question on the table is, what should children be taught and when?

This time, we tried to craft scenarios that range from very easy — meaning we think most people would be fine with them — to very difficult, meaning we think few people would be fine with them. And to cover a full range of ways in which LGBTQ topics might come up. We have stuff about sex, which is a thing Republicans like to fixate on. And then things we think might be more banal, like a teacher being gay or trans or having a pride sticker on the wall.

There are enormous partisan differences, compared to race and sex. Gaps in support between Republicans and Democrats on these items are sometimes as large as 50 points. There’s not a single one of the 24 scenarios we asked about that include LGBTQ issues where Republicans support even high schoolers having access. Republicans are so opposed to virtually all these scenarios that something like 20 of the questions have 10% support or less.

Democrats are pretty mixed about elementary school. They support family-related items, like the teacher having a picture of their same-sex spouse on their desk or the book about same-sex penguin adoption, And Tango Makes Three. But on a lot of items, majorities of Democrats aren’t in support in elementary grades, whereas at the high school level they are definitely in support of all items.

Trans-related items are the ones with the largest partisan gaps at the high school level, with Democrats still not over the moon — 67% support — but Republicans very, very opposed.

Did you identify possibilities or opportunities for a path forward?

I would say we didn’t. But we can draw some conclusions that could inform a path forward. Respondents really seem to have read the items in our survey and thought about them because you see a big range in terms of what they support and what they oppose. That’s important information. We really do need to have a discussion about what’s age-appropriate, what parents want and kids need. And that’s probably not going to be one conversation. That’s probably going to be 50 conversations, one in each state. Or maybe 13,000 conversations, one in each district.

You can’t just say what’s right is the Republican approach, the [Florida Gov.] Ron DeSantis approach, which is to ban this stuff altogether, don’t talk about it at all, which is not really tenable. But the Democratic approach — which is not super clear but seems to be something like, “Let teachers do what they want and if you have concerns, you’re a bigot” — that strategy doesn’t seem to be particularly useful.

People need something to grab onto. We need some reasonable folks to propose different ways of including LGBTQ issues in the curriculum.

The other thing our results point to is this issue of how schools actually deal with parent concerns. We asked a series of questions about that, and the one-sentence takeaway is people haven’t really thought about this.

Parents’ right to opt their kids out is easy to support because of course parents should have that right. But the reality is, how are schools supposed to deal with the fact that, with very few exceptions, every classroom is a purple classroom, meaning it has Republican parents and Democratic parents? You could easily have people wanting to opt out on one side or people raising concerns on another and it quickly spirals into ridiculousness. How are schools supposed to deal with this?

I’m comfortable with some reasonably constrained opt-out provisions for material that parents don’t want their kids exposed to. I think that’s not a crazy relief valve for these particularly hot-button issues. But we need to come up with policies that are actually implementable, that aren’t going to be incredibly onerous on teachers, aren’t going to have kids missing half the days of the school year, that are reasonably constrained in terms of what they allow and don’t allow.

You tested two ways of asking about opting out. What did the results tell you?

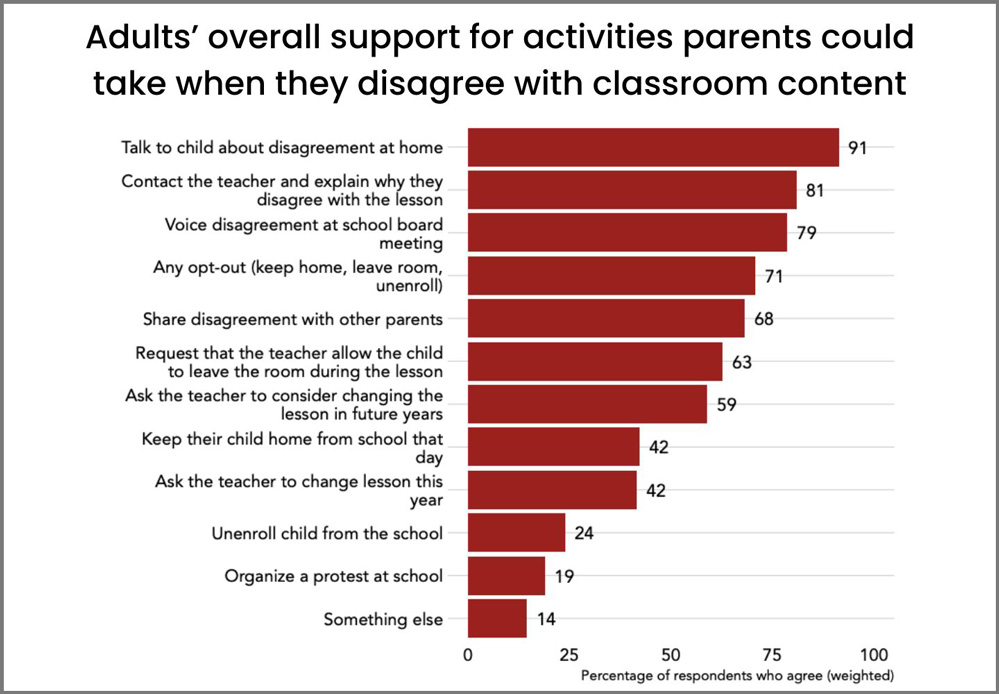

We looked at the opt-out question a few ways. We asked people what they thought were reasonable responses from parents who disagree with the content of a lesson and gave, like, 10 different options. Pretty much everyone thinks it’s reasonable to talk about these issues, to voice your disagreement either to your child or the teacher or even at a school board meeting.

There’s much more of a mix in terms of whether you think it’s appropriate to ask the teacher to change the lesson. Relatively few people think that more extreme examples, like un-enrolling your child from the school or organizing a protest, are reasonable responses.

We asked a question about how people think schools should react when parents express concern. Again, we found that people don’t really have a great answer, because once you start to get down to brass tacks about how you’re going to handle these, it gets really complicated really fast.

Democrats are more likely to say the school should teach the lesson as planned if a parent objects, but not even a majority of Democrats — only 48%. We asked how, if multiple parents disagree, should the school make a decision? Again, we got a lot of mixed answers. Mostly, though, people say educators or school boards should be the final deciders on these issues.

Then we did this cool little experiment. We wanted to see whether we could affect people’s views about opt-out by giving them some information about what the potential impact could be. So we randomly split the sample and gave half of them a paragraph with a little scenario that said the teacher believes all students should participate because learning about content they might not otherwise hear helps them see a new perspective, learn to be a critical thinker or simply learn a new important fact. And it can be hard for a teacher to accommodate every parent’s wishes for every lesson for every child.

And then we asked people who did and did not get that paragraph whether they supported opting out. We saw that exposure to an argument about the potential negative effects of opt-out actually pretty substantially reduced people’s support for opting out.

What I think this tells us is not about the specific language of that proposal, but that this is an issue where people’s minds aren’t 100% made up. Supposing a school had an opt-out policy and gave parents messages about why they think that, “Yes, you can opt your kids out, but we don’t think that’s a great idea for XYZ reasons” — that actually would affect people’s actions.

People’s views on this are pretty malleable. And people haven’t really thought through the practical consequences. So there is potential to shape attitudes and actions.

It reminds me of the retrenchment that LGBTQ advocates did after losing in Maine, where in 2009 voters overturned a law allowing gays and lesbians to marry. To prepare for the 2012 vote that re-legalized same-sex marriage, social scientists figured out that framing the issue as one of rights did not move the needle. But asking a prospective voter, “What does your marriage mean to you?” actually changed the conversation.

Republicans are really good at message discipline and Democrats are not. These are not like sure-thing issues — especially on trans issues. A lot of people don’t understand trans issues and are uncomfortable with them. A lot of people are uncomfortable with having to use different pronouns and things like that.

I’m a real believer that there are ways that you can change people’s attitudes based on how you talk about things. I think the strategy of, “if you don’t do things perfectly then we’re going to ostracize you and call you a bigot” — that’s not a winning strategy. You need to change hearts and minds.

We did it with same-sex marriage for the most part, though you know lots of Republicans are still opposed to that. But we won the policy battle, at least for now. And I think that we can do that on some of these LGBT- and race-related issues in schools. But again, it’s not clear.

There are arguments you can make on some of these topics where it’s not clear there’s a right answer. Another example would be schools getting information about a child and hiding that from the child’s parents. That’s an issue where I certainly can understand why schools might feel the need to do that. At the same time, I can understand why parents will be very upset If they learned that that was happening. There’s just lots to unpack here.

But to get back to your question, yes, the messaging clearly matters. You need to figure out what messages are resonating with people, what arguments will work to persuade them. I’m sure they exist.