Sidewalk School, born of Trump’s ‘Remain in Mexico’ policy, goes virtual amid pandemic

Jo Napolitano | June 30, 2020

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

In 2019, The Sidewalk School opened in a cramped tent city on the U.S.-Mexico border. Now its students, craving educational opportunities in the States, face their latest challenge: learning during a pandemic

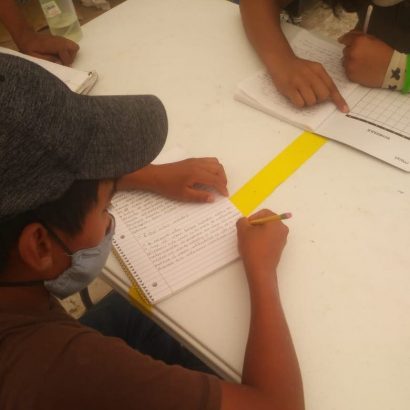

Eager to continue their education, asylum-seeking children waiting on the Mexican side of the border with their families study wherever and whenever they can. Many of those pictured here in Matamoros, Mexico, just a few miles south of Brownsville, Texas, attend The Sidewalk School, a nonprofit created in 2019 by two American volunteers who hope to prepare these children for the American public school system. But it is unclear if they will cross: The Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy and the pandemic have left families stranded. (Getty Images)

The Sidewalk School in Matamoros, Mexico, founded last summer by two American volunteers, defied convention from the start. Located just three miles from the border with the United States, it had no brick-and-mortar building, no buses, classrooms, blackboards or desks.

For months, its students, asylum seekers waiting with their families for permission to enter the country, met outdoors before moving to an abandoned tent — at least until the pandemic struck.

Then this school born of hardship, where children wrote while lying on the pavement before someone donated dozens of lapdesks, did something remarkable: It went virtual.

Teachers who for months delivered lessons in person adapted to distance learning, transmitting their instruction to students via 235 tablets bought by the school.

The switch is a major challenge for staff and students, but participating children are determined not to waste the opportunity. Each hopes to one day cross the border and enroll in an American public school.

The Sidewalk School’s co-founders, Felicia Rangel-Samponaro and Victor Cavazos, both of Brownsville, Texas, call their students’ dedication inspiring.

Victor Cavazos and Felicia Rangel-Samponaro stand outside a Matamoros encampment on a recent afternoon. The pair met in 2018, handing out food to those making their way north. They opened The Sidewalk School in August 2019. (Courtesy of Felicia Rangel-Samponaro)

“To go to school in that situation,” Rangel-Samponaro said, her voice breaking, “I couldn’t do it. And they keep turning in work and showing up day after day. That’s a strength a lot of people don’t have. Yesterday, when it was flooding, they still showed up. They are still thriving, wanting to learn.”

Rangel-Samponaro and Cavazos met in November 2018 while delivering food to a steady stream of newcomers making their way north. Back then, the faces changed daily and the pair were content with their roles, considering the turnover.

But that all changed when the Trump administration began requiring many asylum seekers to remain in Mexico until their cases are processed. The policy, implemented in late January 2019, has been hailed as a success by the White House as it’s kept some 60,000 people from entering the United States. It also has resulted in numerous encampments on the Mexican side of the border, including one in Matamoros that has swelled to 2,500.

“Suddenly,” Rangel-Samponaro said, “the faces stopped changing.”

Building a school

It was then that the former teacher, who lives just three miles north of the site in South Texas, was moved to do something more for the children, who often passed their days near the foot of the Gateway International Bridge playing with rocks and dirt or sitting idly through what should have been a day inside a classroom.

Rangel-Samponaro and Cavazos opened The Sidewalk School in August 2019. The nonprofit takes its name from its original location: With no real campus, children learned while sitting on the sidewalk near the encampment.

Its founders called on the asylum seekers themselves — there were teachers among them — to form its staff.

“I know there are a lot more opportunities there. Expectations are also greater, but I know I’m up for the challenge.” —Cesia Merary Mejia Bachez, 12, of El Salvador and a student at The Sidewalk School, on public schools in the United States

The school has grown in size and scope: The faculty has expanded from four to 11 teachers plus six teaching assistants and a librarian, all paid a modest salary of $12 a day. The Sidewalk School’s founders know it’s far less than they are worth, but it’s all the organization can afford while also buying books, pens, pencils, paper, art supplies and other items for its students.

The school has also employed five seamstresses since the pandemic who make hundreds of cloth face masks for $40 a week. The money, at first drawn from Rangel-Samponaro’s own savings, now comes from the school’s GoFundMe page.

Sidewalk School students, who study everything from math to science and English, range in age from 1 to 16. The organization used to offer day care services but discontinued the practice during the pandemic.

Its teachers’ work is not unlike that of their American counterparts. Instructors follow a curriculum, write lesson plans and select books they hope their students will find relevant and inspiring as they struggle to learn under the most challenging of circumstances.

“The school is really where our hearts are,” Cavazos said. “I know for my children to grow up in a world where they are seen as equal to their peers, I must stand up and fight for our people and do everything I can to give them a better future.”

View of a migrants’ camp on the Mexican border just south of the Rio Grande, in Matamoros, Tamaulipas state, Mexico, near the border with the United States, on Nov. 1, 2019. (Photo by Lexie Harrison-Cripps/AFP via Getty Images)

The Sidewalk School is not immune to the crime that has plagued the encampment from the start. Two staff members were kidnapped on the same day in October 2019, according to Rangel-Samponaro and Cavazos. Each was held for ransom and eventually returned after their tormentors squeezed money from their relatives abroad.

Such incidents are commonplace: Local crime syndicates are well aware that those who seek to make the journey north often have family in the United States. Some asylum seekers have been kidnapped more than once.

‘Let’s go virtual’

Prior to the pandemic, some 125 children met their teachers daily, crowding around several tables, with the school providing lunch, school supplies and other much-needed staples, including powdered milk, toiletries, vitamins and detergent.

Classes were supposed to have been canceled in mid-March when the virus was first detected in Matamoros. But Rangel-Samponaro and Cavazos didn’t want to just pack up and leave. Their students deserved better, they said: They deserved distance learning.

In addition to paying modest salaries to staff, The Sidewalk School also buys vitamins and other essentials, including toiletries, tents and detergent, for students and their families. (Felicia Rangel-Samponaro)

The organization had about $20,000 in its coffers, and Rangel-Samponaro knew exactly what to do with it.

“I said, ‘Let’s start buying tablets and let’s go virtual,’” she said.

Rangel-Samponaro and Cavazos hoped the children would adapt to remote instruction, but they refused to remain at home with their families. They wanted to be together, and nearly all of them showed up at the tent for class. They couldn’t understand why they were no longer permitted to meet in person: Despite the pandemic, the children played together all day long and lived just a few feet from one another, they reasoned.

Realizing they would not relent, Rangel-Samponaro canceled school for a week and devised a plan she hoped would keep them safe. She allowed a small number of students to study in the tent in shifts throughout the day — teachers’ aides, who live inside the encampment, were allowed on site — but only if they agreed to comply with strict guidelines.

All who entered were required to wear face masks, and their hands had to be sanitized by a staff member.

The school purchased 20 no-touch thermometers, two for each staffer assigned to monitor the students’ entrance, “so, if something happened to one, they had a backup,” Rangel-Samponaro said.

Staffers placed tape on the tables and benches so children knew where to sit in order to keep six feet apart. And they wiped down all surfaces with strong disinfectant multiple times a day.

Social distancing

In many ways, circumstance forced The Sidewalk School to implement a plan that others around the world are only just now developing. As those schools might soon learn, safety remains a constant concern despite strict protocols.

“I don’t think people understand what an encampment is, how small it is, how people live in the woods, one on top of the other,” Rangel-Samponaro said. “Social distancing cannot happen. We try, but it is impossible inside an encampment. They have over 2,000 people living in a small place.”

Mexican officials prohibited the school from using the tent in May. They have, however, allowed staff to set up three tables in the open air to allow schooling to continue while curbing the spread of the virus. So far, no one inside the encampment has become ill from the disease, Rangel-Samponaro said.

She’s also implemented rules for the staff. The Sidewalk School’s teachers live off-site in an apartment building closer to downtown Matamoros, a busy city visited by locals and tourists alike. The teachers frequently travel to area shops and have more exposure to a wider swath of people, Rangel-Samponaro said. As a result, they are not permitted to come face to face with students: They all teach remotely, even though they are just a short walk from the encampment.

Sidewalk School students, pictured here in April, continue to focus on their education despite numerous obstacles. Though they are unsure when they might be able to cross into the United States, each is eager to enroll in an American public school and plans to come prepared. (Felicia Rangel-Samponaro)

Ray Rodriguez, 36 and from Cuba, taught at The Sidewalk School for months before crossing over to the United States in January. A former college professor who left his home country in part because the government was trying to influence his curriculum, he now teaches remotely from Washington, D.C.

He credits The Sidewalk School for allowing students a break from the reality of sleeping on the floor, of watching their parents fret about their future, of recounting the horrors of home in preparation for critical meetings with U.S. immigration officials.

“Living in that environment is not healthy at all,” said Rodriguez, adding that the trauma the students have experienced has taken an enormous emotional toll.

He recalls, back when he was living inside the encampment, asking a little girl to tell him a story as a way to stir her imagination. He thought the child, about 7, might recount a beloved fairy tale.

Instead, she told him of how her aunt was raped and murdered by police.

“That was not the story I wanted, but it was the one she memorized,” he said. “They think that is normal.”

“I don’t think people understand what an encampment is, how small it is, how people live in the woods, one on top of the other. Social distancing cannot happen.” —Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, co-founder of The Sidewalk School

Rodriguez hopes his students win passage to America, but for now, the possibility is remote. Not only did the United States effectively close its border with Mexico and Canada as a result of the pandemic, but it has delayed immigration hearings and turned away thousands of asylum seekers with minimal processing.

Wherever they land, Rodriguez said, he hopes his students have a chance to be children once more. Until then, he’s glad to help fill in the gaps in their education and prepare them for what comes next.

‘Up for the challenge’

Rodney Prepo, 27 and from Venezuela, taught at The Sidewalk School for several months before crossing the border and moving near Monterey, California, in March. He loves teaching civics because it helps children understand the importance of being good neighbors and working to keep the encampment as clean as possible.

“I wanted the kids to have respect for other people, for the rules, to live better,” he said.

Young asylum seekers who might otherwise spend their days in Matamoros playing with rocks and dirt inside their encampment can instead focus on their education at The Sidewalk School as they wait for an opportunity to cross the border into the United States. (Felicia Rangel-Samponaro)

Living better is the entire reason Nora Reyes, 32, and her family left El Salvador.

Her husband and eldest son fled the country in April 2019 and have since made it to Boston. Reyes and her two youngest children departed a few months later, in August.

“We didn’t have the money to leave together,” she explained in a telephone interview from the camp.

The family hoped for a speedy reunion, but she and the two youngest have been stuck in Mexico for nearly a year.

Though she laments their 13-month separation, The Sidewalk School has been a tremendous help through the crisis. Reyes’s son, 7-year-old Salomon, struggled with reading when he first arrived in Matamoros, but his ability has since improved, she said. Her little boy agreed.

“I’m learning consonants and vowels,” he explained, standing by his mother’s side. “I like learning new things.”

Reyes’s 4-year-old daughter, Milagros, also a student at the school, has already learned her numbers and the alphabet.

“She looks forward to her schoolwork,” her mother said.

A mural stands near shelters known as macro tents, recently constructed by the Mexican government, in the border town of Matamoros, Mexico. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Twelve-year-old Cesia Merary Mejia Bachez of El Salvador is thrilled to have the opportunity to learn English. Cesia, also reached by phone inside the encampment, is a gifted student. Her family left home for several reasons — they were being threatened by local gangs — but also so that she could focus on her education.

“We know my daughter is very advanced,” said her mother, Claudia, 39. “She has a lot of potential. We will encourage her to live up to it when we get to the States.”

Cesia has not yet decided on a career path, but she feels well prepared for the rigors of the American school system.

“I know there are a lot more opportunities there,” she said. “Expectations are also greater, but I know I’m up for the challenge.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.