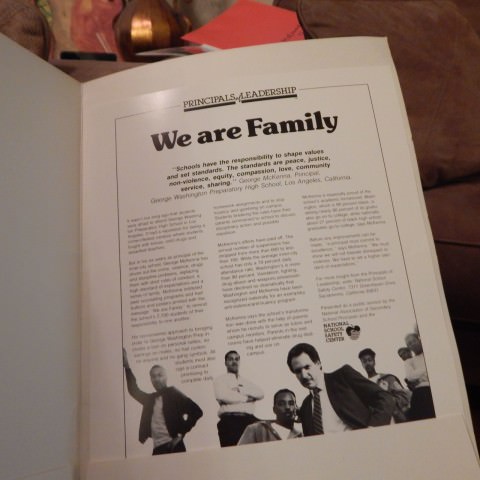

A movie, a principal and a turnaround school: 30 years since ‘The George McKenna Story’

Mike Szymanski | March 7, 2016

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

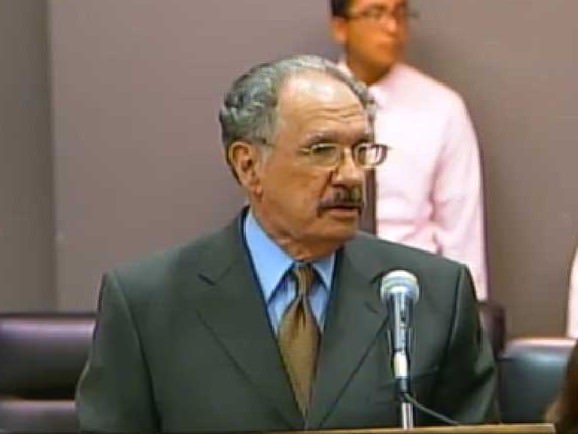

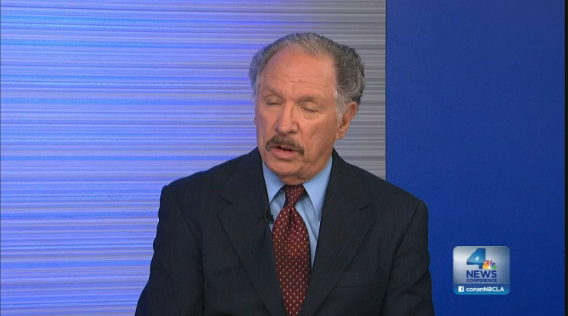

George McKenna doesn’t talk about it much, but Denzel Washington played him in a TV movie called “The George McKenna Story.”

Fellow LA Unified school board members may occasionally rib him about it, and on a recent tour of an elementary school, Superintendent Michelle King pointed it out to impress the students. “This man had a movie made about him, and Denzel Washington played him,” King said as the students exclaimed, “Ooooh!”

McKenna gave his characteristically self-deprecating “aw-shucks” response and said about the two-time Academy Award winner, “You kids probably don’t even know who that is anymore.”

This year marks the 30th anniversary of that CBS-TV movie, about a principal who transformed a gang-infested South LA high school filled with graffiti and fear into a place students wanted to attend, and where they thrived. A great deal has changed in the three decades since the movie was made about this success in the LA educational system, but some things remain the same — and still need fixing.

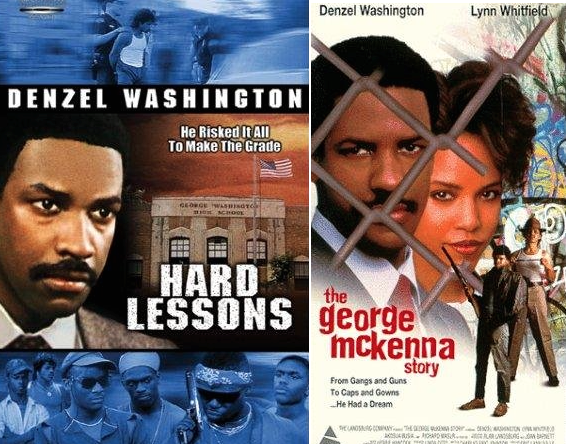

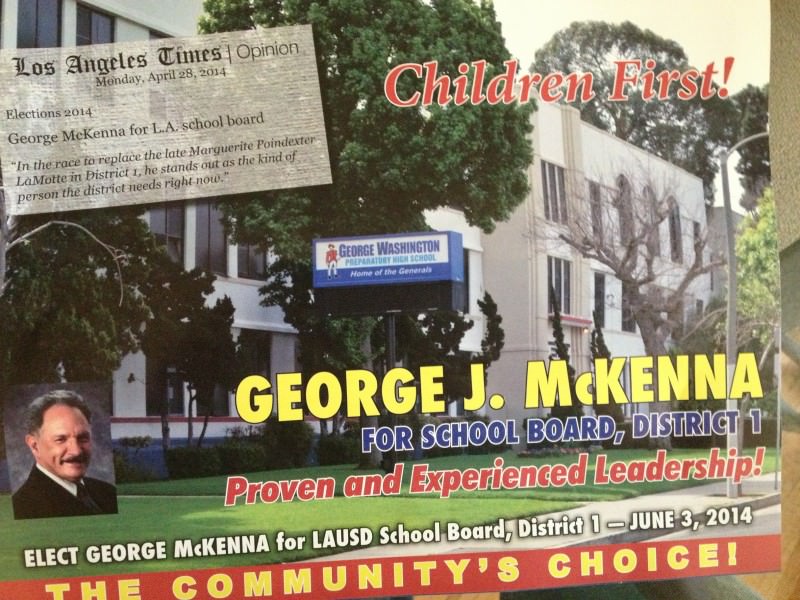

Posters for the movie based on George McKenna’s school success in South LA.

McKenna was at first surprised when told by LA School Report that it had been so long since the movie’s release. “Time really goes by fast,” said the 75-year-old as he looked at the DVD version of the film, which has been re-titled “Hard Lessons.” (The movie is free online.) He didn’t have a copy of the movie until recently when he received it as a birthday present. McKenna, notorious for not talking to the media, agreed to discuss the anniversary and the issues the movie raised.

“I was a little embarrassed when the movie first came out,” McKenna admitted. “My ego is not that big, I never tried to seek that out, I was just doing my job.”

Sign up for newsletters from LA School Report

The movie opens in 1979 with McKenna arriving at Washington High School in South Los Angeles on his first day as principal. He meets resistance, particularly from a teacher who reports him to the district on trumped-up charges. Students are skeptical, and a parent activist, Margaret Wright, warns him, “I got you hired, I can get you fired.”

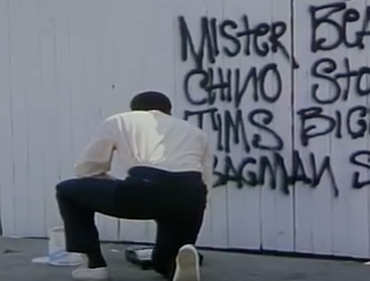

Then a promising young athlete is shot just off campus in a gang fight and dies in the principal’s arms. That incident, like the rest of the movie, was true, McKenna said, adding about the death, “It was one of the toughest moments of my life.” The gang fight motivates the principal to step up changes both on campus — which he does with the help of an idealistic white teacher — and off campus, including painting over graffiti on a wall across the street and recruiting the football team to help. In the end, the graffiti is eradicated, students thrive and the principal is a hero. (Get a full synopsis and other facts about the movie here.)

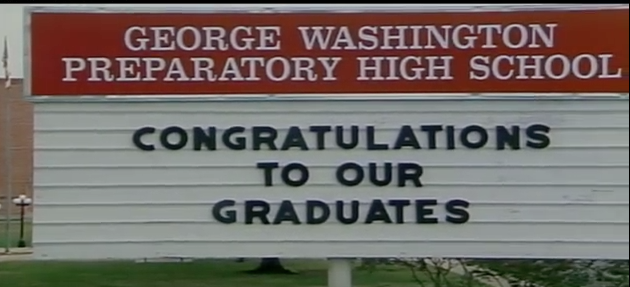

Above, Denzel Washington walking into Washington High for the first time, and below, the actual logo at the school.

McKenna’s own voice is heard at the end of the movie, as he credits the changes to the group efforts of parents, students, staff, community and teachers. He says: “Some of the dreams at Washington Preparatory High School have come true. Attendance is now at 90 percent, and 70 percent of the graduates have gone on to college in each of the past four years. We now have a waiting list to enter our school. The school stands as a role model for what can be done at all public schools when responsibility is taken by the professionals and the entire community. The triumph of Washington Prep can be shared by all of us.”

Changes good and bad

Thirty years later, much has changed, including names: The movie has been retitled. McKenna is now Dr. George McKenna, after earning a doctorate in education from Xavier University. Washington High is now Washington Preparatory High School.

After the film, the school received many grants and motivation by the district to create Performing Arts, Math/Science and Communication Arts magnets. The school now has championship sports teams that have earned dozens of students full college scholarships. In 2006, it became part of LA Unified’s Small Learning Communities program in which the school was divided into more specific areas of interest including Engineering and Technology, Business, Health and Fitness and more.

“The school used to have 3,000 students, and when I got there, there were 1,700 and enough spaces for a whole other school,” McKenna said. Today, about 2,400 attend the school.

The school’s demographics have shifted. African-Americans, who then made up 90 percent of the student population, are now 48 percent; 49 percent are Latino. About 71 percent are socioeconomically disadvantaged, 54 percent are English learners and 52 percent have disabilities.

Progress has slid from the height of the McKenna era. Today, only about 70 percent of the students have high or near perfect attendance, while 27 percent are chronically absent. The graduation rate has fallen below the state average to 71 percent, and only 27 percent are college ready. In a district that strives to have zero suspensions, 26 students were suspended last year.

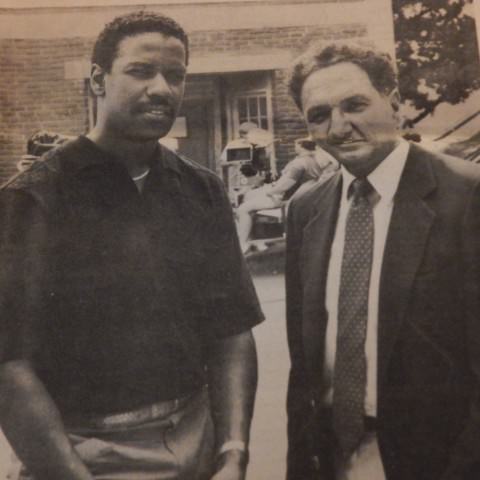

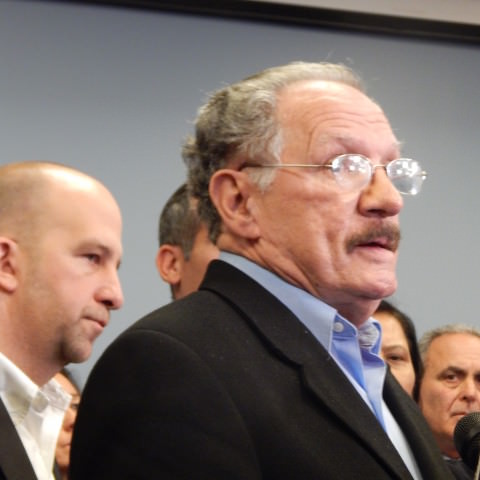

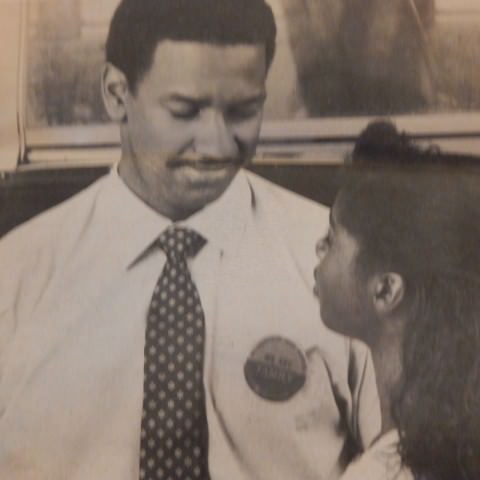

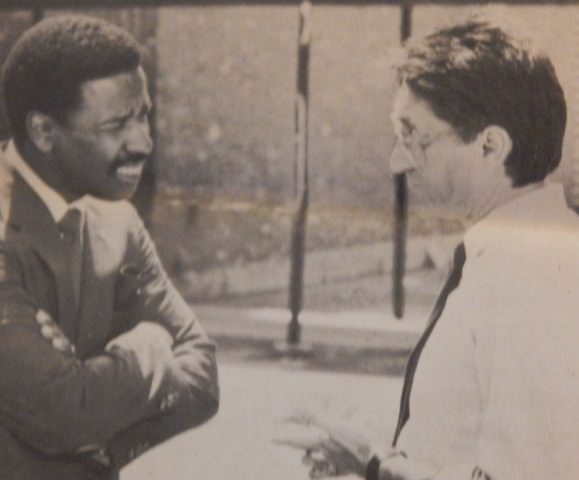

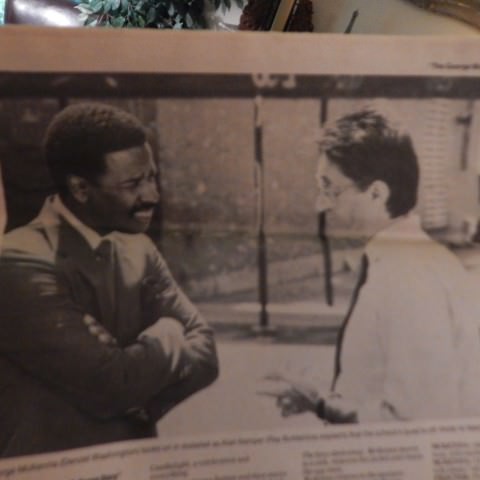

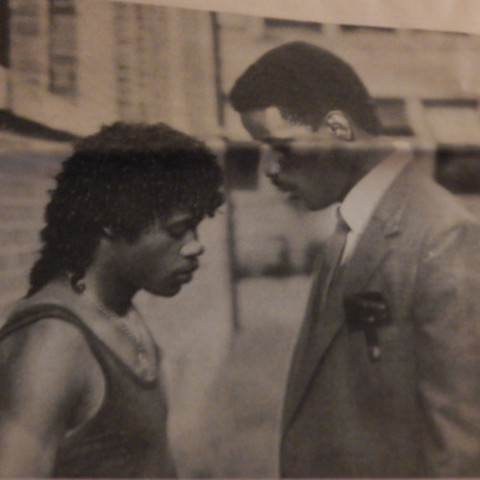

The real George McKenna, and Denzel Washington portraying him.

Only 14 percent of the students are enrolled in at least one Advanced Placement course, compared to the state average of 22 percent. In the McKenna era, 80 percent of the school’s graduates went to college; only 69 percent now say in a recent survey that they even aspire to get a college degree.

“Some things have gone backwards, it’s out of my control, but ultimately that school and all the schools in the district are much, much safer,” McKenna said. No school has metal detectors anymore, although random wanding is still done. Graffiti is gone, they have a dress code, and Washington Prep won’t let students participate in after-school activities unless they have a high attendance record.

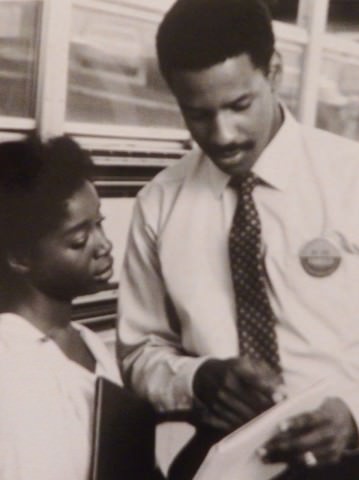

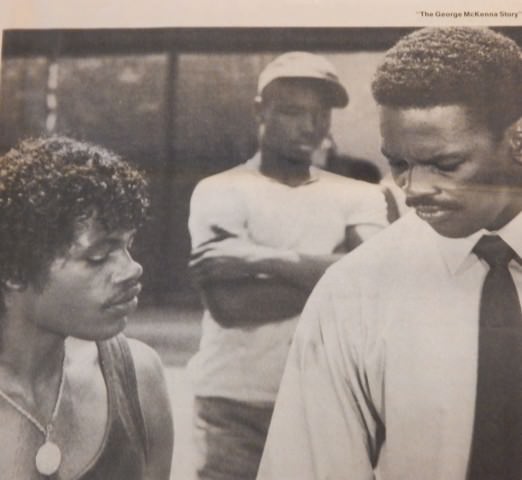

A student dies in McKenna’s arms in the movie.

A half-dozen principals have come and gone since McKenna left in 1986, including his friend Marguerite LaMotte, who went on to be elected to the school board. McKenna succeeded her to the school board after her death in 2013.

“The key to the success of a school is the principal, and the worst thing a school can have is a mediocre principal, not just lousy, but mediocre,” explained McKenna, who then launched one of his famous McKenna-isms that made his classroom teachings so entertaining and long school board meetings less boring. “It’s like a square circle. You can say it, but you can’t draw it.”

McKenna insisted, “The principal is the single most powerful position in public education. A principal is more important than a superintendent, board members, mayors, anything. That principal’s work ethic, skill set and value system will affect everybody in the school, adults particularly, and the children and families that send their kids to that school. They all look to the principal.”

McKenna doesn’t blame recent principals for failing to keep up some of the successes he achieved at Washington High. He said the community and district have to continue to support those successes, and that takes a lot of extra work. “There’s a big difference between blame and responsibility,” he said. “It’s not your fault that they came this way, but now they’re in front of you. They’re yours, and the principal is responsible whether the grass grows. You don’t have to be a gardener, but you can’t just let the grass die. You have to figure it out and find somebody to help you keep the grass growing.”

Principal supporter

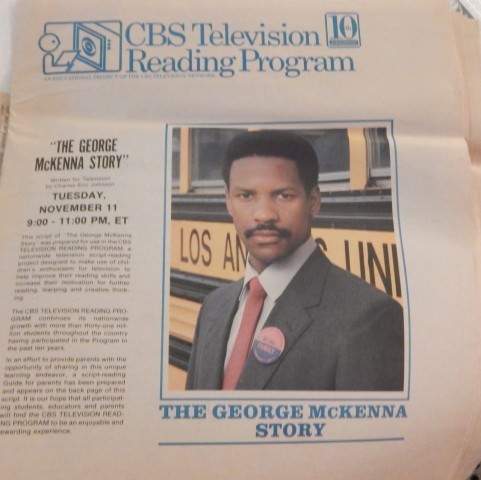

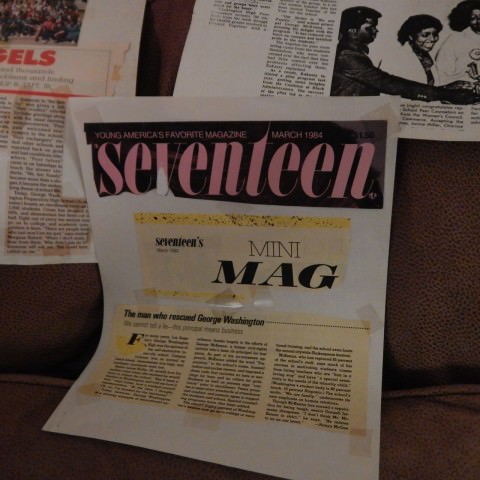

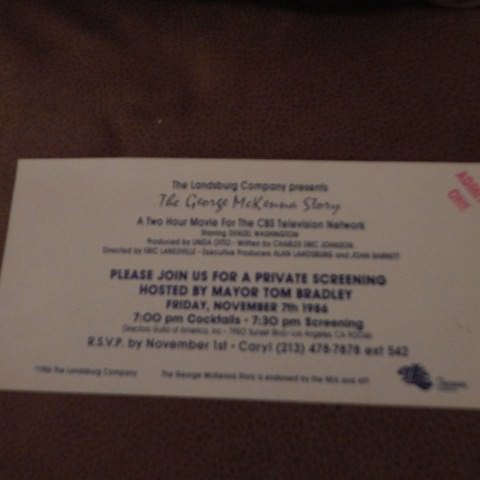

That somebody in the movie, and in real life, is McKenna supporter Allan Kakassy, who retired in 2005 after 37 years in LA Unified and 17 years at Washington Prep. Now 70, Kakassy fondly remembers the McKenna years at the school and has kept two large bins of archives, articles, videos and pamphlets about the movie in his home in the San Fernando Valley. He claims to have the largest collection of McKenna archives, including his ticket to the movie premiere as well as teaching guides that CBS sent out to instructors throughout the country when the movie aired. He also was one of the real-life characters portrayed in the film who met with the writers and filmmakers during the making of the movie.

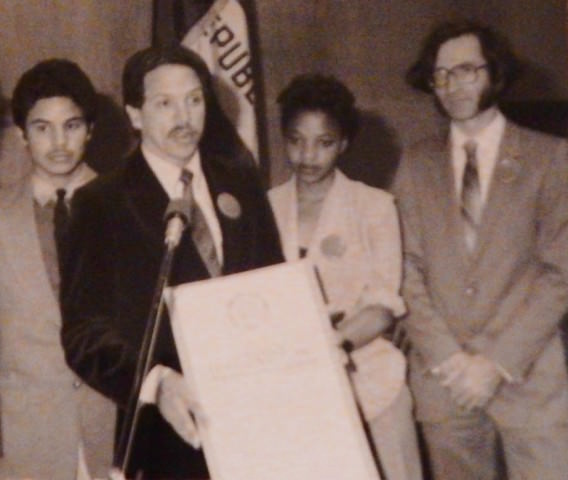

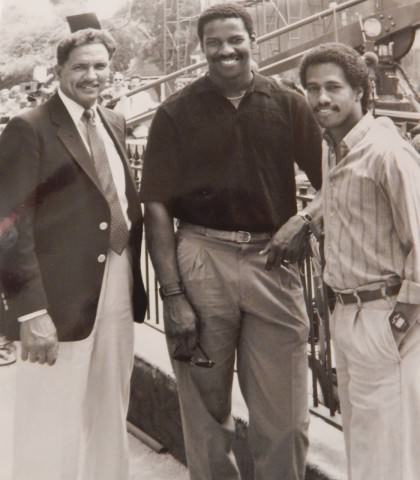

McKenna and Allan Kakassy as they are portrayed in the film.

“I remember the first time he appeared at Washington High with the teachers in the cafeteria and spoke about hope and collaboration and how he was determined to make the changes, it was just like in the film,” Kakassy reminisced. “He had a sense of determination, never believing something can’t be done.”

Kakassy recalled the unrelenting resistance by many of the teachers. In the first three years under McKenna, 122 of the 142 teachers transferred to another school or resigned. But many other teachers wanted to come to the school under McKenna, Kakassy said, and the school had a waiting list of 350 students by the time McKenna left.

“Quite a few teachers did leave, they just gave up,” said Kakassy, who has also collected some of the educator’s favorite quotes. “McKenna wanted us to fill out extra paperwork, make phone calls to students’ homes, stay a bit later to tutor. It wasn’t really too much, but it was enough to cause resistance. He had a precise way of identifying what needed to be done and how to do it.”

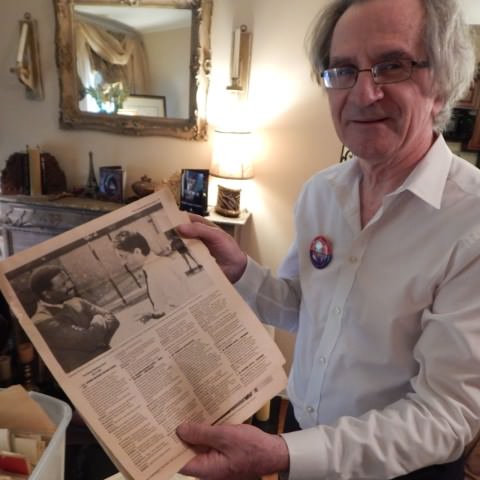

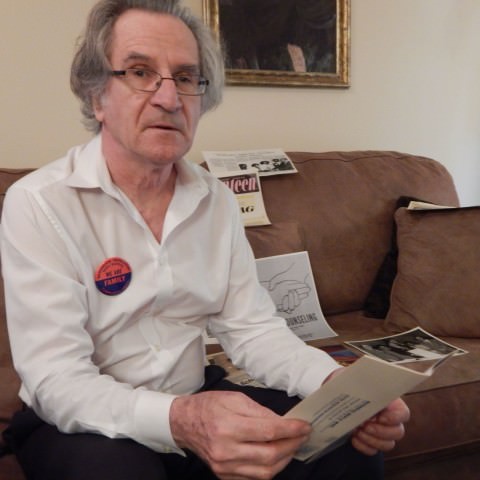

Allan Kakassy with his McKenna archives.

Kakassy said the movie didn’t show the whole story. “In the movie, I was the white young liberal who came to the principal’s defense, but it doesn’t show how the union at the time and even the district made it so very hard for him,” Kakassy recalled. “Now the unions support him, but at first they were all resistant to change. And the district told him to stand down.”

The original script depicted more of an overall struggle to change the education system as a whole. But it was rewritten to become a more traditional story of a heroic principal fighting gang violence.

“George McKenna wanted to change the system, he is a pioneer,” Kakassy said, welling up with tears as he recalled his days at Washington Prep. “People thought he was autocratic or dictatorial, but he was just the opposite. He loves the kids. He hates the system. He’s still trying to change it.”

Kakassy added, “It is a significant part of the aftermath of the movie that George McKenna is now on the school board, and maybe he can change things from there.”

McKenna said a significant way of changing the system is to repeat best practices and share what is working among teachers and schools. Some of the changes he made at Washington Prep were implemented at hundreds of schools throughout the nation. Many schools adopted his parent-student-teacher contracts that spell out specific responsibilities for each regarding a student’s education. With the help of the TV studio, McKenna’s school reforms were shared with districts throughout the nation and adopted in professional development trainings.

He received more than 400 citations and awards recognizing his work in education, including the Congressional Black Caucus’ Chairman’s Award in 1989, and was named to the National Alliance of Black School Educators’ Hall of Fame in 1997. President Ronald Reagan invited him to the White House to honor his work a year after the movie aired, and he was mentioned in Michael Dukakis’s Democratic nomination speech in 1988.

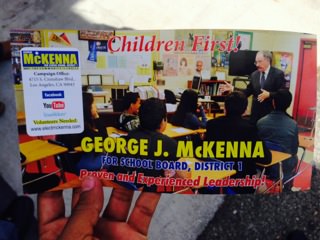

McKenna left Washington Prep to serve as superintendent of Inglewood Unified School District until 1992, and then worked as deputy superintendent of Compton Unified until 2001 and then as assistant superintendent of Pasadena Unified until 2008. Ultimately, he would return to LA Unified, where he began as a math teacher in 1962, as a school board member. He ran unopposed in the last election and will serve until 2020.

Denzel Washington with McKenna on the set.

“My challenge, my struggle, has been to get the system to change,” McKenna explained. “I don’t ask principals to change the world, just change that part of the world where you have some control and some responsibility.”

How the movie got made

The idea of the movie ignited when the husband-and-wife producing team of Alan Landsburg and Linda Otto came to McKenna after reading some of the dramatic accounts of what was happening at the school in the local newspapers.

“They said they were looking for something like a sequel of ‘To Sir, With Love’ and tell a story of what would happen to the Sidney Poitier character in this situation,” McKenna recalled. “I was flattered. The school was showing progress in ways that were unexpected, so it became news. But a movie should not be about a school that works. It should work. Why should it be celebratory when it does work rather than invoking outrage when it doesn’t?”

At the time, movies about inner city schools were novel. The movie “Stand and Deliver” about tough LA Unified teacher Jaime Escalante (which earned Edward James Olmos an Academy Award nomination) came out two years later. The Poitier movie was made in 1967.

Young actor/director Eric Laneuville, whose mother was a Washington High counselor and worked with McKenna, was tapped to direct the film. Laneuville co-starred in the medical TV drama “St. Elsewhere” and directed some episodes. He suggested the up-and-coming actor playing Dr. Chandler for the lead role.

Washington Prep now.

“I met Denzel on location, it was made at a school in Houston,” McKenna remembered. (The actual school couldn’t accommodate such a large film shoot, so the production moved out of state.) “I was able to get kids from the local high school to get bit parts in the movie. They enjoyed that.”

McKenna laughed about the choice of Washington playing him. McKenna was born in New Orleans as a very light-skinned Creole black man. He grew up in an area where certain social privileges or club memberships were allowed if your skin passed “the paper bag test.” If your skin was darker than a brown paper bag, you couldn’t belong. McKenna is much lighter. And so, a darker actor playing the African-American principal was about the only part of the film that wasn’t quite accurate.

“I was very impressed with Denzel, and he talked to me about the part,” McKenna related. “He followed me around a couple of days at school, but kids didn’t mob him because he wasn’t so famous at that time. He tried to do my accent. Of course, he went on to do a lot of other great roles after that.”

The year the movie came out, the actor spoke at the graduation ceremonies, and of course the kids were thrilled, McKenna said.

“All the parts in the movie were real, everything happened, it was factual,” said McKenna, who read all versions of the script. “It happened in a much shorter time in the movie, though, when in reality it took a period of two or three years.”

McKenna’s love interest in the movie was a composite character of women long gone. He points out that high school principals have the second highest divorce rate, beaten only by undercover cops.

“I have never been married, no wife, no kids,” McKenna mused. “I don’t blame it on the job, but I accept the fact that that’s the way it’s supposed to be. I raised all kinds of other children in the schools.”

It wasn’t shown in the movie, but he kept a toothbrush and tie in his office when he slept over at school. He often worked weekends, checking teachers’ plans and tutoring students. He attended all the athletic events and held regular assemblies with male and female students separately where they could ask him any question that was concerning them — about life, family, love, drugs, sex, homework, college, anything.

The antagonist in the movie — the teacher who had it out for McKenna — was also a composite. “There were people who pushed back,” McKenna said. “Change was not on their agenda. A lot of people believed that all you needed to do was contain children rather than emancipate them. Education is the primary vehicle for the underrepresented community to be emancipated through the educational process.

“The movie was being made almost for the wrong reason, it was celebrating a school that works, and how that’s unusual,” McKenna pointed out. “And I would ask teachers why things were so wrong and why their students were getting D’s and they talked about the gangs, the violence, the poverty, the drugs, all kinds of factors that wasn’t looking at themselves. But they didn’t ask for help. It’s we shall overcome, not I.”

“The movie was being made almost for the wrong reason, it was celebrating a school that works, and how that’s unusual,” McKenna pointed out. “And I would ask teachers why things were so wrong and why their students were getting D’s and they talked about the gangs, the violence, the poverty, the drugs, all kinds of factors that wasn’t looking at themselves. But they didn’t ask for help. It’s we shall overcome, not I.”

If they need help, they should go paint that proverbial fence across the street, McKenna insists. He had to paint that fence over and over again in the movie (and in reality), and finally asked the football team for help.

“I had to bully the kids,” he said. “I had to say, ‘You are on my football team, you have responsibility. You come over here and help me paint the fence. Guess who decides who the coach is, and who plays on this team? I got your helmets, I got your shoulder pads, I got your jockstrap, and you are not going to go on my field with my uniform on and not help me get this graffiti off.’ And we had to paint that graffiti off a number of times.”

McKenna continued, “What really changed was the people in those houses, the mamas and grandpas, who came out and gave them lemonade and some cookies and thanked the kids. That was personal, and that’s when the graffiti stopped.”

Washington High School with building named for Margaret Wright, depicted in the film.

School notoriety, the famous and infamous

Washington High was built in 1926 in the Westmont section of unincorporated Los Angeles County. Famous alumni include swimmer and actress Esther Williams, former LA County district attorney Gil Garcetti, surf guitarist Dick Dale and pro football player Hugh McElhenny. Later, actor/rapper Ice Cube, actress and singer Teresa Graves and many pro football and basketball stars would graduate from the school.

McKenna explained that the Watts Riots in 1965 scared many of the white families out of the area. Gangs formed and drugs were sold openly. McKenna said he witnessed the birth of the Bloods and Crips in his school neighborhood. Some of the most infamous gang leaders were in Kakassy’s classes.

“McKenna made students feel safe to come back where some of the country’s most notorious gangs began,” Kakassy said. “He pointed out that neglect was detrimental to the community and the students. It was important to be hard on the system, because there was an environment of uncaring. And yet, people resisted. How can George McKenna’s message be controversial? He is expecting a high level of behavior of the staff and the community for the best of the children!”

Kakassy added: “And how many high school principals are invited by the president to the White House?”

McKenna downplays the fanfare surrounding him, like when high-profile black politicians Maxine Waters and Jesse Jackson came to his school board inauguration ceremony. “I don’t know Jesse personally, but it was an honor to have him there,” McKenna said. “That was a bit embarrassing too.”

McKenna said, “The reality is that it’s not about a celebrity, or a movie, or a book, it’s about what we do and how we try very hard in the classroom. My soul is with the classroom teacher.”

McKenna notes that there are still schools nationwide like Washington High in the movie, but he is sure that there aren’t any that bad in LA Unified anymore.

“If the adults around don’t have sufficient commitment to let no child escape, then the situation in the schools will just get worse,” McKenna warned. “The classroom can be a place of salvation or a place of condemnation.”

Even now as a school board member, McKenna said changing the system is still a challenge. But he said he hopes his position will facilitate those changes, and quickly.

“Patience is not a virtue, it runs out on all of us, and there will still be things I need to get done when my time runs out,” McKenna said, smiling. Then, pulling out another McKenna-ism, he added, “Someday is not on the calendar. It is not a day of the week. For me, it’s now.”

- Invitation to the screening of the film

- Denzel with McKenna on the set

- McKenna, Kakassy and two students depicted in the film

- The new and improved Washington Prep.

- McKenna, Washington and director

- Allan Kakassy with his McKenna Archives

- Margaret Wright has a building named after her at the school.

- Washington High depicted in the movie.

- Washington Prep now.

- Washington Prep now.

- Principal holding youth as he dies

- From the movie

- The movie was shot at a school resembling Washington but in Houston

- Washington Prep now

- George McKenna at inauguration with Scott Schmerelson

- George McKenna

- George McKenna being honored

- George McKenna, flanked by Bernard Parks and Jan Perry

- George McKenna’s Campaign Launch

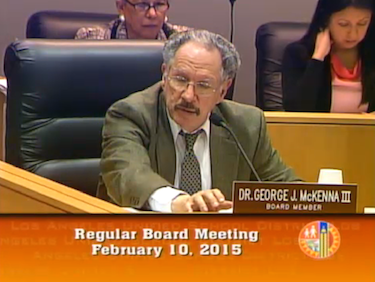

- McKenna at the school board

- George McKenna’s Campaign Launch

- Allan Kakassy today

- Characters of McKenna and Kakassy in the film

- McKenna talks to gang leader

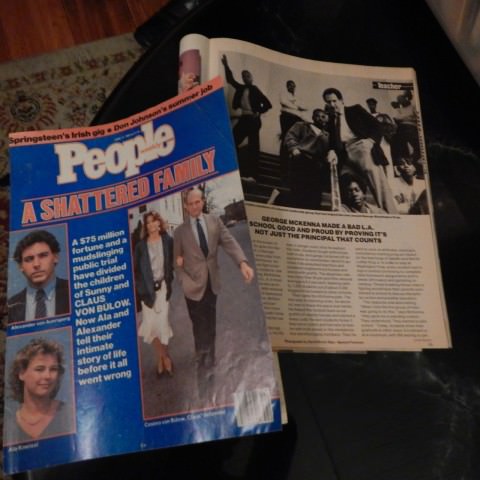

- A feature in People Magazine

- Articles about McKenna

- Back of the invitation