A pre-COVID education study with big implications for remote learning during the pandemic: When parents take over, children give up easier

Asher Lehrer-Small | March 1, 2021

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

* One lace loops to make the trunk. A squirrel runs around the tree, jumps into a hole at the bottom, and comes out the other side. Pull it though and… huzzah! *

* One lace loops to make the trunk. A squirrel runs around the tree, jumps into a hole at the bottom, and comes out the other side. Pull it though and… huzzah! *

Teaching a child to tie their shoes isn’t always easy. If you’ve embarked on this painstaking task, watching as little fingers fumble with floppy laces, chances are you’ve fought the urge to jump in and finish the job.

However, new research out of the University of Pennsylvania suggests that parents may want to think twice before taking over — advice that likely comes as no surprise to mothers and fathers, but goes far beyond shoe-tying.

The study, published in the journal Child Development, finds that jumping in and completing a task that a child is working on can stifle perseverance and cause them to persist less in the future.

“If your kid is working on something and you step in and do it for them,” Allyson Mackey, a study co-author and professor of psychology at UPenn, explained to The 74, “then they will learn that you didn’t think they could do it. And they might try less hard in the future.”

WATCH — Mackey talks about the new research showing kids give up easier if parents step in:

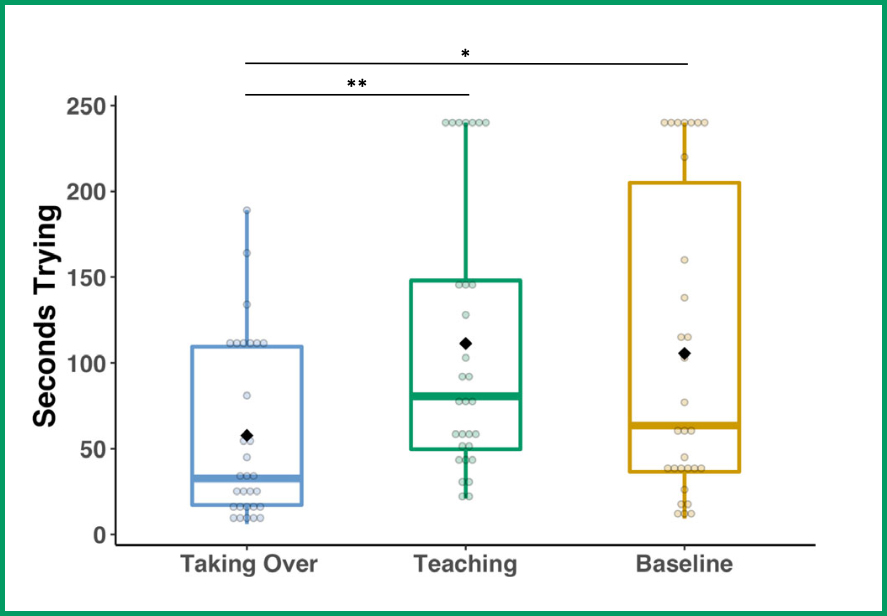

The experiment, carried out pre-pandemic at a children’s museum in Philadelphia, randomly assigned 90 4- and 5-year olds to one of three groups. One group received patient teaching from a lab technician on how to solve a preliminary puzzle. Another group struggled for just a short time with the puzzle before the experimenter jumped in to solve it. The third was the control group, which received no pre-experiment assignment or instruction.

All children were then given an impossible task: open a box, secretly glued shut, that had an object rattling inside. If they succeeded, the experimenters told the children, they would be able to play with an exciting toy. The researchers measured how long the kids worked at the task, and compared across groups.

The results were stark. Kids whose lab technicians took over and solved their puzzles persisted at the box task for an average of 50 seconds — about half as long as children who had received the teaching treatment or no treatment at all.

Kids whose lab technicians took over and solved their puzzles persisted at the box task for about half as long as children who had received the teaching treatment or no treatment at all. (Child Development)

The behavior of “trying,” it turns out, is a learned skill. When parents make a habit of jumping in and completing the tasks that their children are working on, it can discourage kids from persisting.

“If [children] learn from their parents that they shouldn’t try, either because they’re likely to fail, or because someone else will do it for them, then they won’t practice trying,” said Mackey. “That will have long-term implications for reward and motivation circuitry in the brain.”

During a pandemic, the lessons from child psychology take on a whole new level of significance. Many parents — including Mackey — increasingly find themselves under the same roof as their kids as they struggle to complete school assignments. And in such cases, resisting the urge to take over becomes all the more important.

In remote learning, the psychologist mother-of-two tries to help make school work fun. She runs races through the house with her kids and uses games to learn spelling.

“What brings joy into our house?” Mackey asks. “Because when [my daughter] is feeling happier, she gets less frustrated. Persisting through reading is easier, persisting through math is more fun.”

The Pennsylvania professor says that she now constantly ponders the messages she might be sending.

“I think about it all the time,” Mackey said, admitting that sometimes it can be difficult not to jump in. “I try to do it less, but it is just really hard. It is really hard to watch a child struggle.”

Though it can be a test of patience, giving young children the time to learn new tasks on their own can yield strong benefits, the researcher says. In her own home, budgeting more time for tasks has been key.

“Building more time into our schedule for practicing, sort of low-stakes tasks, I think has helped quite a lot,” Mackey said.

She cautioned against taking this tactic too far, however. Parents should avoid the example of “bean dad,” who went viral on Twitter in January for refusing to feed his hungry daughter. The stubborn parent opted instead to let the 9-year-old learn to use a can opener through hours of fruitless experimentation.

“That is not the right way to motivate kids,” Mackey said. “As soon as children, especially young children, are frustrated, you really can’t bring them back.”

In case you missed Bean Dad aka john roderick before he deleted his Twitter account, this is what started it all. pic.twitter.com/KCKRP3099c

— ColinT has Maniacal Ventures (@ManiacalV) January 3, 2021

Her rule of thumb? “Do not step in until your child asks for help,” she advises parents.

If her daughter is working on a task, say a puzzle or her homework, Mackey will often visibly busy herself with something she knows her daughter will understand — reading a book or washing dishes, for instance. It can make her daughter be less quick to interrupt by asking for help, and can encourage her to persist longer.

Cultivating persistence, however, is just one piece of healthy childhood development, Mackey explained. Her UPenn colleague Angela Duckworth, a much-lauded researcher, has championed the concept of “grit,” which Mackey said includes not only perseverance, but also a spark of “passionate interest” that compels youth to work toward their goals.

Parents can support their children in many ways: By modeling effort themselves, by cheering on their kids through difficult tasks, by documenting their kids’ progress, and by praising effort instead of ability. One out-of-the-box tactic, tested by research, suggests parents can even encourage healthy decision-making by dressing their kids up as a favorite superhero, Batman for example, and then asking, “What would Batman do in this situation?”

But beyond any one “do” or “don’t” for parenting, balance is key. Raising happy kids, Mackey says, is the first step to raising kids who persevere.

“I really believe that general brain health, general well-being is essential for any kind of learning, for any kind of motivation or persistence,” she said.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.