A problem for math teachers: Solving the dilemma of learning lost to a year of Zoom

Jo Napolitano | June 1, 2021

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

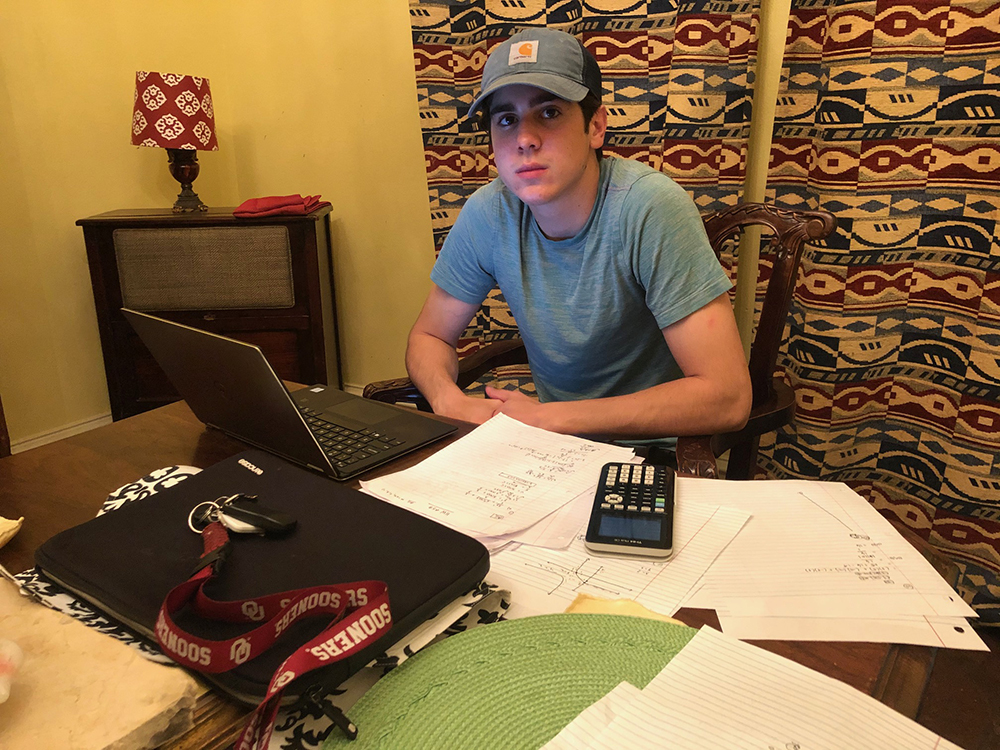

Christopher Ochoa of McAllen, Texas, has loved mathematics since he was a young child, his interest fueled by summer-time math camps and trips to Space Center Houston.

The high school senior’s strong work ethic helped him manage his ADHD, dyslexia, and sensory overload well enough to earn stellar marks and gain entry to Texas A&M University.

But during the pandemic, both his grades and his academic confidence plummeted.

“When you’re in the classroom, you can ask a question, go to the whiteboard with your teacher and he’ll work through it with you,” the 18-year-old said. “Now, when you ask a question, you have to unmute your mic and you can’t see the teacher face to face or make eye contact. It’s just not the same. There isn’t that physical interaction.”

Chris Ochoa sits at his family kitchen table on a recent evening. Ochoa, a solid math student already accepted to Texas A&M University, has struggled to keep high marks in the subject during the pandemic. (Carrie Manthey Ochoa)

Teachers say pandemic-related setbacks in mathematics will linger well into the coming school year, especially for students who suffered the most during shutdowns. Unable to peer over their students’ shoulders and correct their work, math teachers lost the ability to offer on-the-spot tutorials. The results showed: A November NWEA study of fall 2020 test scores for nearly 4.4 million children in grades 3 through 8 found they lagged 5 to 10 percentage points in math compared to students in the prior year.

Chase Nordengren, a senior research scientist at NWEA, said math-related learning loss in the upper elementary and middle school grades has been stark, mirroring what happened to students who suffered through Hurricane Katrina.

He’s unsurprised by the timing: It’s in the later elementary years that students tackle computational arithmetic and conceptual thinking — including fractions and ratios — for the first time. “It’s not hard to imagine those skills are more difficult to teach remotely,” he said.

(Jennifer Kennard/Getty Images)

Matthew Reames, a fifth grade math teacher at Daniel Morgan Intermediate School in Winchester, Virginia, said distance learning has hindered some students’ ability to build their skills.

“The way the standards are set up, the kids really need to master every single thing in that grade to be successful the next year,” Reames said. “Even if you are missing one little thing, it might amplify itself later on.”

Matthew Reames, is a fifth grade math teacher at Daniel Morgan Intermediate School in Winchester, Virginia, said a gap in students’ skills in mathematics will hinder their ability to learn new concepts. (John Westervelt)

Other subjects, including science, don’t face the same hurdles, he said.

“If you don’t understand the water cycle, that won’t put you at a disadvantage with magnets,” he said. “You might have gaps in what you know but it is not a specific skill. Math is a whole lot of skills and concepts that build on themselves from year to year. There is not really anything you can leave out. And that’s true whether you are in a pandemic or not. Each year, we look for these gaps.”

And there are other challenges, too, as the pandemic lingers and even worsens in some areas. Trevor Doyle, a middle school math teacher in Camino, California, remains on a hybrid schedule a year into the crisis. Students attend school in the mornings or afternoons for just three hours, four days a week, with Mondays reserved for planning and meetings. It’s simply not enough time to keep them on track, he said.

Doyle is not new to the profession. He’s taught mathematics for 18 years, including three at Folsom State Prison. But nothing could prepare him for the challenges brought on by distance learning.

He believes 80 percent of his students will have made up for what they lost during the next school year.

But he’s less optimistic about the remaining 20 percent. It could take that group twice as long because the school could not offer on-site remediation during shutdowns. Prior to the pandemic, struggling students were invited to school an hour early and for another 45 minutes after the last bell rang — in addition to working through lunch.

Now, a sizable portion of his students are floundering, including those who struggled in school prior to the shutdowns and whose parents are unable to hold them accountable for online coursework.

“It’s that middle-of-the-road kid who needs that extra push, who is the furthest behind,” he said.

Summer school might help, Doyle said. President Biden’s American Rescue Plan requires states to invest at least $1.2 billion in summer enrichment programs. Doyle’s own district saw a fourfold increase in such spending, and is planning an intensive summer program focused almost solely on academics.

But he does not expect it will make up for all that was lost.

“A lot of teachers are expecting to reteach material at the beginning of next year,” Doyle said.

Yvonne Calderon said it’s not only those children from disadvantaged backgrounds who are struggling during the pandemic. Even more well-off students have lost ground. Calderon teaches 7th grade mathematics at an affluent private school in Tempe, Arizona, one that has been in-person most of the school year.

All of her students have experienced at least some trauma related to the pandemic, she said. Several told her they suffer from anxiety and many are having difficulty retaining what they’ve been taught.

She’s found herself reteaching concepts these students should have mastered years ago.

“Despite wealth, these children still face challenges within their own families,” Calderon said. “I have years of experience in teaching math and I have never seen this before.”

Danilsa Fernandez teaches middle- and high school algebra at City College Academy of the Arts in New York City. Dubbed a master teacher by the non-profit Math for America, a New York City-based group that supports educators and improves retention, she stayed on task for much of the school year until a pandemic-related closure in mid-March.

But even after her students returned, she had reason to revisit concepts she’d taught before: The transition back to in-person learning allowed her to see more of her students’ work, which reflected their inability to master key concepts.

Danilsa Fernandez, who teaches middle- and high school algebra at City College Academy of the Arts in New York City, didn’t realize the extent to which her students failed to pick up key concepts in mathematics until they returned to school. (Danilsa Fernandez)

“Mistakes that were easily hidden behind a computer screen were now in full display,” she said. “I decided it would benefit the students to re-discover some topics without rushing through the material.”

Eighth grader Jaslyn Ovalles is one of Fernandez’ students. She struggled mightily with online learning: Her grades dropped sharply across every subject.

“It’s hard when you are at home because you are in your own environment,” said Jaslyn, 13, who spent part of each day looking after her four younger siblings. “Not all of your teachers require you to turn on your camera, so you can use your phone, watch TV while you’re sitting in your bed or on the couch. It’s easy to fall asleep.”

Once she returned to campus, Jaslyn’s grade shot up almost immediately.

“If I could just get my grades up in science, I’d be passing all my classes,” she said.

Nordengren, of NWEA, advises teachers to take the time to understand each child’s abilities and be sure not to waste precious time reteaching concepts they have already mastered or skipping ahead to topics for which they are unprepared.

He said parents can help, too, by incorporating math in their everyday life — grocery store check-out lines can provide a great opportunity to consider addition, subtraction, percentages and other, more complex topics — and by not speaking negatively about the subject in front of their children.

“If you have a parent that says, ‘I’m not a math person,’ or ‘We are not math people,’ that will put that deficit mindset into a kid’s brain,” Nordengren said.

Ochoa never had that problem, until now. He’ll spend his summer working with a tutor trying to undo it.

And while he was thrilled to gain entry to Texas A&M, he made a last-minute switch to the University of Oklahoma, a smaller school that would offer him far more academic support, something he values after such a difficult year.

“Whatever I missed in online learning, I can learn there and be better prepared,” he said. “I’d rather be ahead than behind.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.