Analysis: Educators’ poor morale matters, even if they don’t quit. Here’s why

Elizabeth D. Steiner, Heather Schwartz & Melissa Kay Diliber | September 14, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Schools have been trying to return to normal after three years of closures, disruption and setbacks, so it’s no surprise that the pandemic has taken a toll on educators’ morale.

Schools have been trying to return to normal after three years of closures, disruption and setbacks, so it’s no surprise that the pandemic has taken a toll on educators’ morale.

Yet, thus far, public school educators nationally have not left their jobs at notably higher rates than before the pandemic began. Even so, poor morale among educators is concerning. Given how many teachers enter the profession through social networks, poor morale among today’s educators might dissuade tomorrow’s from entering the field. This sets up possible future teacher shortages in an already thin market. Moreover, teachers who are stressed out are absent often, and educator burnout can harm student achievement. Together, these factors could hamper students’ efforts to recover from pandemic-related disruptions to schooling.

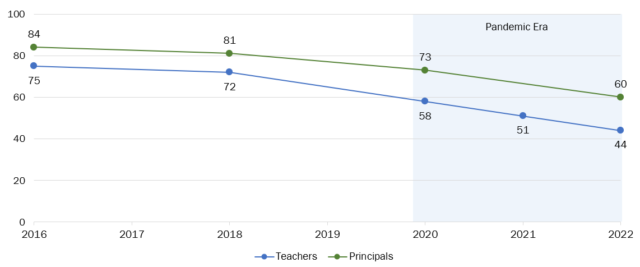

Percentage of teachers and principals who say the stress and disappointments of the job are worth it

All estimates come from nationally representative samples of teachers and principals. Data for teachers and principals in 2016 and 2018 come from the 2015-2016 and 2017-18 editions, respectively, of the National Teacher and Principal Survey conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics and were pulled from the NTPS data tool. Data for teachers and principals in 2020 come from RAND’s October 2020 COVID-19 surveys. Data for teachers in January 2021 come from RAND’s 2021 State of the Teacher survey. Data for teachers and principals in January 2022 come from RAND’s 2022 State of the Teacher and Principal surveys. In all cases, principals were asked to what extent they agree with the statement, “The stress and disappointments involved in being a principal at this school aren’t really worth it.” Teachers were asked to what extent they agree that “The stress and disappointments involved in teaching at this school aren’t really worth it,” although in 2021 and 2022 the survey item did not specify “at this school.”

But not all educators’ morale has been equally affected by the pandemic. In our nationally representative American Educator Panel surveys, morale has significantly declined among principals and teachers throughout the pandemic — but not among superintendents. As of spring 2022, 85% of superintendents said that, considering everything, they are satisfied with their jobs. Eighty-seven percent feel valued, despite most saying their job is getting harder. In contrast, only 44% of teachers and 60% of principals feel the stress and disappointments of their job are worth it—satisfaction levels far below what they were before the pandemic began.

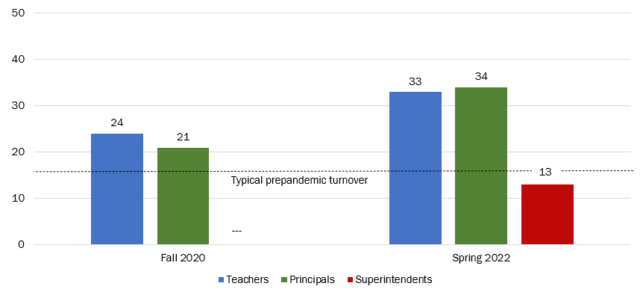

Likewise, only 13% of superintendents said they plan to leave their positions by the end of the 2021-22 school year, compared to 33% of teachers and 34% of principals. Importantly, the proportion of superintendents who said they plan to leave is on par with pre-pandemic annual turnover estimates, while the proportion of teachers and principals who said they intend to leave has grown throughout the pandemic and is now significantly higher than the percentage of teachers and principals who typically leave in a single school year. Of course, survey responses about intention to leave often overstate actual turnover. But the disparity between superintendents on the one hand and the teachers and principals on the other provide a potentially important clue about the reasons for the divergence in educators’ morale.

Percentage of educators who reported intentions to leave their jobs by the end of the current school year

All estimates come from nationally representative samples of teachers and principals. Data on teachers’ and principals’ intentions to leave their jobs come from RAND’s October 2020 COVID-19 surveys and RAND’s 2022 State of the Teacher and Principal surveys. In both surveys, teachers and principals were asked “What is the likelihood that you will leave your job by the end of the current school year, compared with the likelihood you would have left your job before COVID-19?”, although the spring 2022 survey item specified “at your school.” Data for superintendents come from RAND’s fifth American School District Panel survey, in which superintendents were asked “In what month and year do you estimate you will leave your current position?” Data on typical pre-pandemic turnover for teachers and principals come from NCES’s Schools and Staffing Teacher and Principal Follow Up Surveys. Data for superintendents come from a study by The School Superintendent Association. Turnover estimates include both those who leave to take positions in other schools and those who leave the profession entirely.

Why are superintendents more satisfied with their jobs right now than teachers and principals? Historically, this has always been the case. We believe the most plausible reason is that superintendents have a greater distance from the classroom. While superintendents might take the heat at public school board meetings, principals and teachers are more often in the position of addressing parent concerns or, in extreme cases, harassment. During the last few years, superintendents were likely not the ones implementing COVID-19 safety protocols in schools, figuring out how to adjust in-person instruction to an online medium on the fly, cope with heightened student misbehavior or combine classrooms to keep schools open amid staffing shortages. These are all things that created additional stress for teachers and principals. Unsurprisingly, 73% of teachers and 85% of principals said they experienced acute job-related stress this past spring — levels that are twice as high as the slightly more 35% of all working adults.

In this light, state and district education leaders can take steps now to reduce teacher principal stress this fall in two ways:

- Recognize that job-related stress is systemic and that educators closer to the classroom may experience more of it. Given how widespread stress is among educators, superintendents should also avoid the appearance of treating teachers’ and principals’ lack of well-being as a superficial or short-term problem.

- Talk with teachers and principals about the sources of stress in their job, and what could alleviate them. The answers may be different in different schools. But local remedies could include creating student tutoring programs, communicating norms for parents about expressing concerns with teachers, making efforts to build collegial adult relationships, and hiring more counselors, teaching assistants, paraprofessionals and other support staff. These are all remedies that can serve as powerful mental health supports and retention tools.