Analysis: How are kids with disabilities doing post-COVID? Shamefully, we still don’t know

Robin Lake | October 26, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Since the start of the pandemic, we at the Center on Reinventing Public Education have had our eyes locked on the experiences of and outcomes for students with disabilities.

Since the start of the pandemic, we at the Center on Reinventing Public Education have had our eyes locked on the experiences of and outcomes for students with disabilities.

As we noted in our inaugural State of the American Student report, students with disabilities lost out on critical therapies and foundational learning and socialization opportunities during the early days of the pandemic. Nearly half (44%) of parents of students with cognitive disabilities reported that schools abandoned their child’s legal right to access an equitable education when they moved to remote learning, according to Understood, a national nonprofit that supports those who think and learn differently.

To establish a baseline understanding of the impact on those students, and to begin to track progress toward helping them recover the knowledge, skills and supports they missed during the pandemic, CRPE commissioned the nonprofit Center for Learner Equity to convene a panel of experts to review the latest research. The goal was to summarize what we know, don’t know and need to know going forward to help students with disabilities.

The top line finding of our new report is — disturbingly — that we still know little about how such students are faring. Less than a third of most rigorous academic studies in the past year disaggregate outcomes for students with disabilities. Most of those few studies are limited to a specific state or locale, which means findings are hard to generalize. Nearly all the studies focus on grades 3 to 8, where state test scores are most readily available.

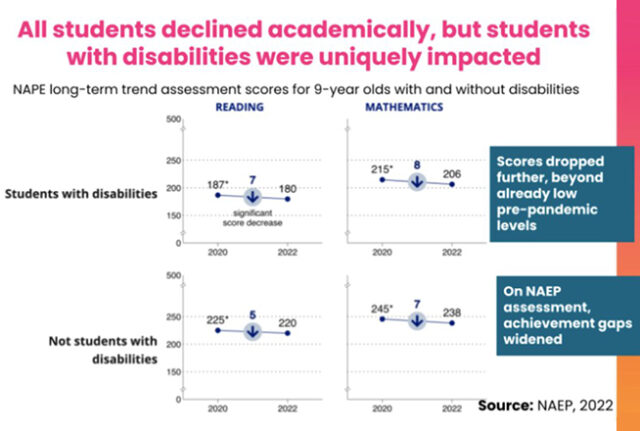

Scores on standardized math and English assessments declined for all students and the same is true for students with disabilities. Results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress showed somewhat sharper drops for students with disabilities than for other children. Different studies show similar or even fewer declines. But any drop in achievement for this group of students should be concerning, as they typically score below their traditionally developing peers to begin with.

We know next to nothing about post-high school outcomes like college enrollment or persistence or employment. High school graduation rates rose for students with disabilities during the pandemic, but it’s unclear if that was a good thing. Requirements were loosened for almost all students, and basic support services for the transition out of high school were fundamentally disrupted.

Another major barrier to parsing the research: Results for students with disabilities are usually reported as a monolithic block, rather than in categories that would note the variation and complexities of real children who have very different abilities and diagnoses, from emotional and behavioral disorders to physical disabilities. The research rarely divides the data to note students with disabilities who may also be facing other challenges, such as economic disadvantage, racial discrimination, or being an English learner or recent immigrant. Our State of the Student report stresses that the averages seen in these reports obscure critical variations in student needs.

The review found little, if any, research on mental health and behavioral outcomes disaggregated for students with disabilities. One exception: a study from a large urban district that shows suspension rates for children with disabilities, particularly Black boys, temporarily increased after a return to in-person learning.

Ameliorating these impacts for students with disabilities may be more difficult than for other students, our new report shows. The research indicates a spike in the number of underqualified special education teachers working in classrooms. In Pennsylvania, the number of emergency-certified special education teachers nearly doubled from 2018 to fall 2020. Nationally, 45% of schools reported at least one vacancy in special education teaching staff positions, according to new data from the National Center for Educational Statistics.

Federal special education law requires school districts to compensate students with disabilities for lost instructional or therapeutic time. But staffing challenges means many schools are likely stretched just trying to deliver regular instruction, much less compensatory services. Across the country, some districts have wrongly asserted that they are not required to compensate for pandemic-related lost instructional time. Only about one in four parents of children with disabilities have received information about compensatory services, and fewer than one in five parents said their child had received those services, according to a national survey conducted by a legal group that protects the rights of students with disabilities. Nearly nine out of 10 parents, however, reported their child experienced learning loss or regression during the pandemic.

Our panel of scholars recommended three steps policymakers can take to better help these students:

- Invest in data and research to track short- and long-term outcomes for students with disabilities and to disaggregate results to specify disability status as well as other factors like race.

- Provide technical assistance to districts struggling to meet such students’ needs.

- Identify and disseminate examples of innovative and effective strategies for educating students with disabilities.

For me, that last point is critical. New online learning tools, innovative staffing models and creative community partnerships can help schools address the immediate needs of students with disabilities. They might also help meet the needs of millions of other children who face unique learning obstacles or emotional challenges. American schools are facing wicked problems. But if educators and communities can explore and implement new approaches to help students with learning differences, the most effective changes might help build toward something better for all students, as well.