Analysis: School safety is about more than keeping guns out of the classroom

Roseanna Ander & Monica Bhatt | September 7, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

In June, after decades of inaction on gun violence, the federal government enacted the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. While limited in its scope compared to the magnitude of America’s gun violence crisis, the law still presents an enormous opportunity to save lives — particularly the lives of children. But that’s not guaranteed. As gun violence experts with decades of combined research and policy experience, we believe the law’s impact will depend on one thing: whether, in spending the billions of dollars in new school safety resources now available through the act, states and cities will follow the evidence about what actually keeps kids safe.

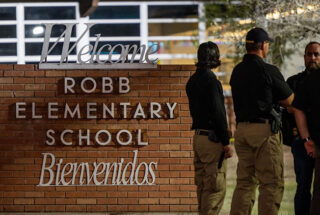

This starts with understanding the nature of America’s gun violence crisis. The tragedy in our backyard in Highland Park, Illinois, over the Fourth of July weekend, not long after the devastation in Uvalde, Texas, was yet another harsh reminder of the impact gun violence has on children and young people in this country. It’s a crisis that’s not confined to Highland Park, Uvalde, Sandy Hook or Parkland, but one that affects cities and rural areas across the country. Every year, approximately 3 million children are exposed to gun violence. Thousands are shot. In our home city of Chicago, roughly 30% of children under the age of 5 live in a community that experiences more than 10 homicides per year.

The ripple effect of gun violence goes far beyond the direct victims and even their immediate families. Research from University of Chicago Crime Lab-affiliated researcher Pat Sharkey shows that exposure to a local homicide disrupts young people’s sleep, interferes with their ability to concentrate and worsens their educational outcomes. Take one stark example: Children who take standardized exams following a homicide on their street test as though they have missed two years of schooling.

This is the “school safety” challenge we face. Yes, it is in part about preventing the 93 in-school shootings that occurred in the last school year alone. But it’s also about ensuring children can walk to class on safe streets without being shot or killed. It’s about keeping students engaged and enrolled in school, because that’s one of the best protective factors against involvement in crime and violence. And it’s about addressing the trauma students bring into the classroom after losing neighbors, friends and family members to this uniquely American epidemic.

The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act provides the opportunity to do all of that. In passing the law, Congress provided billions of dollars to help state, cities and districts reduce community violence and increase school safety. But how they spend this money will determine whether the law will have an impact. Traditionally, school safety funding has been used to harden buildings by purchasing things like metal detectors and employing armed security guards.

Truly keeping kids safe means making a different bet, one backed by data and evidence: advancing programs that help young people cope with trauma while developing tools to de-escalate arguments before they lead to violence. At our research organizations, the University of Chicago Crime Lab and University of Chicago Education Lab, we have conducted randomized controlled trials — the gold standard in scientific evidence — of several such programs that show enormous promise.

One of these programs, Choose to Change (C2C), connects students at risk of gun violence with trauma-informed therapy and supports. The therapy aims to help youth manage their emotions and understand how past traumatic experiences, such as witnessing gun violence in their community, can impact their thinking and behavior. Through exercises and conversation, participants learn to build problem-solving and communication skills. Our researchers found that participants in C2C had 48% fewer violent crime arrests and 32% fewer school misconduct incidents than their control group peers, and these changes persist: Preliminary results suggest C2C reduces violent crime arrests for over 2½ years after the program ends.

Results from another program, Becoming A Man (BAM), are equally encouraging. Like C2C, BAM uses role-playing and group exercises to help young people in grades 7 to 12 make more deliberate decisions and de-escalate arguments. One exercise practiced in the program, called the fist, is illustrative: Two teens are paired up; one is given a rubber ball, and the other has 30 seconds to get the ball out of his partner’s fist. Inevitably, the teens end up wrestling over the ball. After they switch roles and the same struggle occurs, the BAM counselor asks why they didn’t simply ask their partner for the ball. It’s a teachable moment: slowing down and thinking before reacting provides the opportunity to consider alternative ways to avoid confrontation. Our evaluation found that by utilizing exercises like this, BAM reduced the number of violent crime arrests among participants by approximately 50% and increased their high school graduation rate by almost 20%.In short, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act can be used to keep children safer in school, if — and only if — funding is directed toward evidence-based solutions that are proven to reduce violence. We’ve done our homework on what works and what doesn’t. Now, it’s time for policymakers to take action.