Analysis: Schools try bonuses, stipends to attract & keep teachers in a tight labor market

Chad Aldeman and Katherine Silberstein | July 27, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

This article originally appeared in the April 2022 School Business Affairs magazine and is reprinted with permission of the Association of School Business Officials International (ASBO). The text herein does not necessarily represent the views or policies of ASBO International, and use of this imprint does not imply any endorsement or recognition by ASBO International and its officers or affiliates.

The competition for labor has never been more intense. In the private sector, the percentage of workers quitting their jobs recently hit an all-time high, as millions of employees searched for higher pay and better working conditions.

The turnover rates in public education are not as high, but schools have still faced staffing challenges that affected their ability to deliver high-quality services this school year. In the fall, there weren’t enough bus drivers to get students to school on time. By winter, the combination of quarantine protocols and a lack of substitute teachers forced schools to scramble to fill classrooms.

As the school year draws to an end, it would be nice to close that chapter and hope that things return to normal. Unfortunately, district labor challenges are unlikely to go away. Even before the pandemic, the U.S. Department of Education reported that the number of newly licensed teachers was down 20% to 30% from a decade ago. Those numbers are not likely to rebound quickly.

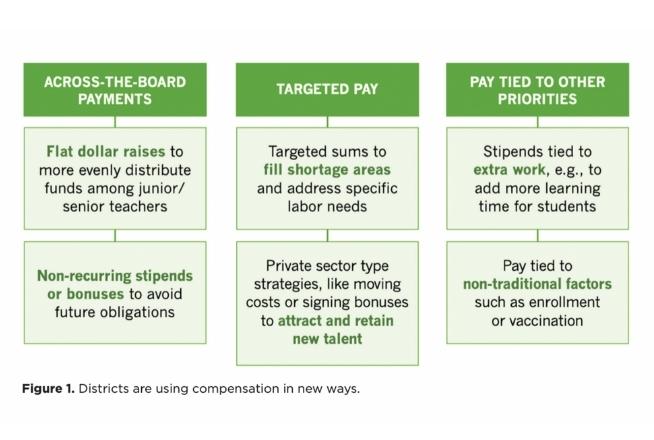

Although it might be tempting to lump all these issues together as a generic labor problem that could be solved with higher salaries across the board, districts will struggle to respond to discrete challenges with universal solutions. As districts work on staffing for the coming school year, they have an opportunity to be creative about how they attract and retain talent.

The exact nature of the challenges varies by community and by position, and the solutions should vary as well. Teacher turnover is consistently higher in some schools, such as those serving a large percentage of high-needs students. Certain subjects — especially special education, math, science, foreign language and English as a second language — suffer from more severe and persistent labor shortages than others. Other districts may be struggling to fill positions for nurses, counselors or aides, food service workers or custodians.

Given the differing market realities, it would make sense to recruit and compensate employees accordingly. Yet school districts historically have been less than eager to use targeted compensation as a tool to attract and retain workers. Most districts use salary schedules that treat all teachers interchangeably, offer the same pay regardless of special expertise and ignore the differences in labor markets for various types of skills.

The pandemic has prompted many districts to adopt new approaches to address their staffing needs. For example, Guilford County Schools in North Carolina offered up to $30,000 extra to newly hired teachers who can show at least three years of highly effective performance and who agree to work for two years in one of the district’s 25 lowest-performing schools. This incentive aimed to bring new employees to the district and tied the amount they received to their incoming performance record.

Dallas Independent School District in Texas offered bilingual teachers a signing incentive of $4,000. DeSoto Independent School District, also in Texas, offered several signing bonuses, including $4,000 for bilingual education and $5,000 for high-need areas, including science, special ed, and career and technical education. Such signing bonuses attract to specific areas qualified workers who might otherwise be inclined to work elsewhere.

Districts also created new, targeted retention bonuses to keep their existing workers. For instance, Detroit Public Schools in Michigan offered a recurring bonus of $15,000 for certified teachers to instruct students with special needs. Austin Independent School District in Texas offered a $2,500 stipend for bilingual support positions and $6,000 for bilingual teachers.

None of these districts completely abandoned their current salary schedules. Instead, they added new, targeted incentives to what they already offer. District employees appreciate predictability, so this layering approach might be a pragmatic way for districts to provide that stability while also targeting their biggest staffing challenges.

Offering financial incentives for hard-to-fill positions is not a new strategy; but as districts experience particular shortages, the targeted money may help. An analysis by the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research suggests that offering stipends in specific shortage areas can improve employee retention rates in those areas.

In addition to targeted incentives, some districts revised their salary scales in ways that bucked the trend of directing larger raises to the most senior employees. For example, rather than raising salaries by the same percentage, which would have given the largest increases to the highest-paid employees, Georgia’s Gwinnett County Public Schools doled out a $2,000 raise to each of its teachers regardless of seniority. A district in Indiana agreed to raise all teacher salaries by $5,000 in 2021 and another $2,000 in 2022. These “flat-dollar” raises treat all workers equally and narrow the discrepancy between lower-paid beginning teachers and their higher-paid veteran colleagues.

Providing larger incentives to junior teachers is also a more responsive approach to historical teacher turnover patterns. Early-career workers are much more likely to leave than their colleagues. Yet research from our colleagues at the Edunomics Lab has found that the average pay schedule tends to withhold the largest rewards for teachers who are already the most inclined to stay.

Before the pandemic, many district leaders might have refrained from these types of compensation changes based on the thinking that “our labor won’t go for that.” That perception appears increasingly outdated. After all, many of the initiatives highlighted here resulted from negotiations with unions. As districts go into their next labor negotiations, they may find an opportunity to think outside their traditional pay scales.

The 2021 school year was an exceptionally tight labor market, leaving employers in every sector struggling to find workers. Although some things may eventually return to normal, district leaders should not count on all of their labor issues to resolve themselves. The past two years have shown that districts can be nimble when they need to be. Beyond the current moment, these types of approaches could pave the way for smarter, more tailored compensation packages that are better for school districts, teachers and students.