Arts education on the ballot: Inside Prop 28 and the campaign to boost K-12 spending by $800 million

Linda Jacobson | October 31, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Students from San Pedro High School marched with former Los Angeles schools chief Austin Beutner on Oct. 2 to campaign for the Arts and Music in Schools ballot proposition. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

Parading down a busy street in San Pedro, a Los Angeles neighborhood, students waved signs over their heads and urged passing cars to support their cause. “Honk for 28!” they yelled. “Say yes on 28.”

The shouting referred to California’s Proposition 28, a ballot initiative that aims to pump at least $800 million into K-12 arts and music programs.

It comes with a pleasing selling point: It won’t increase taxes. That’s one reason no one is raising money to defeat the measure — a relief to former Los Angeles schools chief Austin Beutner, who led the effort to get the question on the ballot and donated over $4 million to the cause.

As superintendent, he and the unions often butted heads. But on that early October day, union members joined him in asking managers of a sandwich shop and a crowded breakfast joint to hang campaign signs in their windows.

“We just want to make sure people know what Prop 28 is,” said Beutner, adding he’s encouraged by the positive reception the measure has received. “It’s been a long time since we’ve had the community of California in support of public education.”

From New Mexico to Massachusetts, voters will decide on several education-related ballot initiatives when they head to the polls Nov. 8. Most propose to raise taxes for additional school funding, but others could decide if all students should get free meals or whether lawmakers can override state board policy.

The California arts measure, however, is decidedly more high profile, attracting support from some big names in the entertainment industry. To promote the initiative, Beutner shared the stage with rappers Dr. Dre and Lil Baby. In San Pedro, “Lord of the Rings” actor Sean Astin pitched in.

“Our members absolutely champion arts and music education in schools. It’s what we’ve built our life and our career on,” said Astin, representing the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. “We think every child, every student deserves [to be] exposed to the arts and music in their public school.”

Actor Sean Astin, far right, joined Austin Beutner and students to campaign for Proposition 28. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

‘The most impact’

Twenty-three states currently provide grant funding for arts education or have a school for the arts, according to the Arts Education Partnership, a project of the Education Commission of the States. But generally, states aren’t required to fund them, said Mary Dell’Erba, the Partnership’s assistant director. Some states fund arts efforts through license plate fees or lottery funding.

Proposition 28 is unique, she said, not just because of the large sums of money it would generate, but the priority it places on arts funding in the state budget.

Called Arts and Music in Schools, the measure would require that 1% above what the state is legally required to spend on education be directed toward the arts. In years when revenues decline, the funding wouldn’t be cut any more than the overall K-12 budget.

Eighty percent of the funds would go toward arts teachers. And while all schools would have access to the funding, 30% would target low-income schools.

To Malissa Shriver, chair of Turnaround Arts: California — a nonprofit that supports school improvement through the arts — that’s huge. When her program began, she said it was hard to find schools that met the organization’s requirement to employ credentialed art teachers.

She gave Beutner credit for “knowing how money bleeds out into administrative costs” and for designing the proposition “in such a way it can have the most impact.” Only 1% can be used for administration and the rest can go toward materials or teacher training.

She argues that along with students’ math and reading achievement, creative expression can help students regroup socially and emotionally after many months of pandemic isolation.

But even if the measure passes, it will face challenges. One is staffing.

“Just because there is a requirement that the funding support educators doesn’t mean there will be educators to hire,” Dell’Erba said.

Some editorial writers have criticized the measure as “ballot box budgeting” and said the state shouldn’t tell local school boards how to spend money.

‘Be who we want to be’

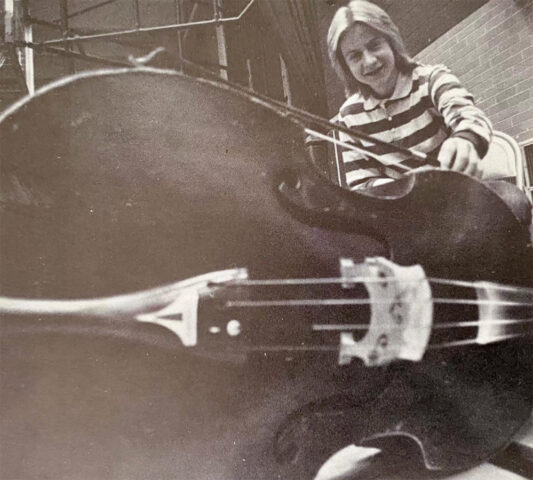

Beutner’s crusade stems partly from his own experience. A shy student in elementary school, he gained confidence after learning to play the cello in fifth grade.

“I could perform in front of thousands of people before I could speak in front of tens of people,” he said. “It all started with that sense of belonging.”

The San Pedro High 12th graders who campaigned with him that day — some dressed in cheerleading uniforms, others holding handmade signs — agreed.

Miki Vasquez, a senior, said art and music “lets us be who we want to be.”

Austin Beutner and Esther Hatch, who works at two Los Angeles Unified schools and has a son in 12th grade at San Pedro High, talked to the manager of the Omelette and Waffle Shop about putting a sign in the window. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

Chris Soto said he’d take a guitar class if one were available. And Isabella Menzel, a first-time campaigner, shouted, “This is the most excited I’ve ever been.”

One student brought “Lord of the Rings” volumes for Astin to sign. After chanting with the students for a few blocks, Astin left early. Currently a graduate student at American University in Washington, studying public administration and policy, he said he had homework to do. “I have an essay due in six hours.”