As California’s new charter law takes effect, schools bracing for shutdowns could win a reprieve from pandemic

Linda Jacobson | November 24, 2020

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

A mural at Lodestar, part of Lighthouse Community Public Schools in Oakland, California (Lighthouse Community Public Schools)

Last year, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a new charter school law intended to settle a longstanding feud between charter operators and those calling for tighter restrictions on their growth.

Known as Assembly Bill 1505, the compromise between charters and the teachers union gave local districts the authority to consider whether the opening of a new charter would negatively impact their own schools, and it gave charters a new process to appeal rejected applications.

But with the law going into effect in the middle of a pandemic, districts lack key information needed to decide whether existing charters should continue operating — assessment data from 2020.

As a result, some schools that otherwise would have been shut down are being recommended for renewal.

Citing “unprecedented circumstances related to the COVID-19 pandemic,” the Los Angeles Unified School District, for example, is recommending “conditional approval” for four of the 26 schools in its first batch of renewals under the new law. “The district is particularly mindful of the need for stability for students and the need to avoid disruption to each student’s educational program during these unique and specific times.” the letter said.

The district is recommending two-year extensions for Ánimo Ellen Ochoa Charter Middle and PUC Excel Charter Academy — both considered low-performing. And it is recommending five-year extensions for middle-performing Ánimo Legacy Charter Middle and Arts in Action Community Middle, but in two years they’ll be reevaluated and could lose their charters if they haven’t improved. Another 22 schools were recommended for five-year renewals.

The schools — which will learn the district’s final decision Nov. 24 at an LAUSD school board meeting — are among 42 in Los Angeles and more than 230 throughout California up for renewal this year. Some districts have yet to hold hearings and school boards across the state will continue considering renewals, likely into 2021.

AB 1505 allows authorizers to consider a charter school’s academic performance — and a variety of other factors — in the renewal process. But with uncertainty about testing for 2021 as well, it’s unclear how long before the new accountability structure will work as intended.

“In the long term, [charter schools] are going to have to live with 1505,” said Jeffrey Macedo, the senior director for communications at the California Charter Schools Association. “But there is a two-year reprieve because of this extraordinary circumstance.”

Schools shouldn’t get ‘a pass’

California, which has the most charters in the country, is only the most visible example of a problem facing charters nationwide: a lack of testing data. But the National Association of Charter School Authorizers urged districts to reject the use of the pandemic as an excuse to delay decisions about charter renewals.

“Schools that have a record of success should not be unfairly penalized with uncertainty in future operations,” such as issuing a short-term renewal when the school has demonstrated it deserves a full term, the organization said in a September statement about accountability.

“On the other end of the spectrum, schools that have a record of significant underperformance should not be excused from accountability. States, authorizers, and districts may wish to alter how they exercise accountability, but simply giving schools a ‘pass’ with a record of failure is not supported.”

In a survey taken during the summer, the association found that 74 percent of authorizers said they were unlikely or very unlikely to postpone renewal decisions, while 18 percent said they were likely or very likely to delay the decisions. The responses came from authorizers overseeing more than half of all charter schools in the country.

The way California and other states handle renewals or approvals this year is likely to be closely watched at a time when a new administration known to be less enthusiastic about school choice enters the White House.

“We hope that President-Elect Biden builds on an eight-year legacy of support for charter schools in the Obama administration, where funding for the federal Charter Schools Program doubled,” said Nina Rees, president and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

And M. Karega Rausch, president and CEO of the authorizers association, added he hopes the transition team is able to “turn the temperature down” on what became a divisive campaign issue.

Macedo, with the California Charter Schools Association, said having state board president and Stanford researcher Linda Darling-Hammond as head of Biden’s transition team for education could be helpful. “We were glad to see that someone we have a relationship with was chosen for that position,” he said. “She hasn’t shown strong opposition.”

Darling-Hammond was actually part of a Stanford University team that co-founded a charter high school in East Palo Alto, and in 2018, she co-wrote a paper that included charters as part of the “tapestry” of public education. It highlights Massachusetts’s rigorous application and renewal process and emphasizes policies that ensure charters are serving the same population of students as district schools.

‘A high bar’

AB 1505, the pandemic — and the recent defeat of a property tax measure that would have raised significantly more money for education — also seem to be having an affect on new applications for charter schools in the state, Macedo said. Currently there are only three open applications statewide and none in Los Angeles. While applications have been declining in recent years, between 2010 and 2015, there were 80 to 100 new charter schools opening in California each year, Macedo said.

Potential charter operators are wondering how to develop a viable business plan “when you’re in a recession and not knowing when it’s going to end,” he said. “How do you model for that?

For existing charters, the new law states that those schools scoring in the top levels of performance can be renewed for as long as seven years, two years longer than previously allowed.

Those in the middle range can receive a five-year extension, and those in lowest ranges either lose their charter or receive a maximum of two years to take “meaningful steps to address the underlying cause or causes of low performance,” according to the law.

In addition, the law required all new teachers hired after July 1 of this year to be certified in the subject or grade level they teach and set deadlines for current charter school teachers to earn credentials by 2025. Those without credentials had to be fingerprinted and undergo a background check.

The legislation sets “a high bar, and I appreciate having a very clear line of accountability, but unfortunately only charter schools are held to that bar,” said Rich Harrison, CEO of Lighthouse Community Public Schools in Oakland.

In October, Harrison faced the Oakland Unified School District Board of Education to make the case for why they should renew charters for two of his schools.

He was pretty confident the district would recommend renewal for the Lighthouse campus, a K-8 school ranked in the middle. But he wasn’t so sure about Lodestar, a K-9 school falling into the low category based on assessment data from 2017-18 and 2018-19.

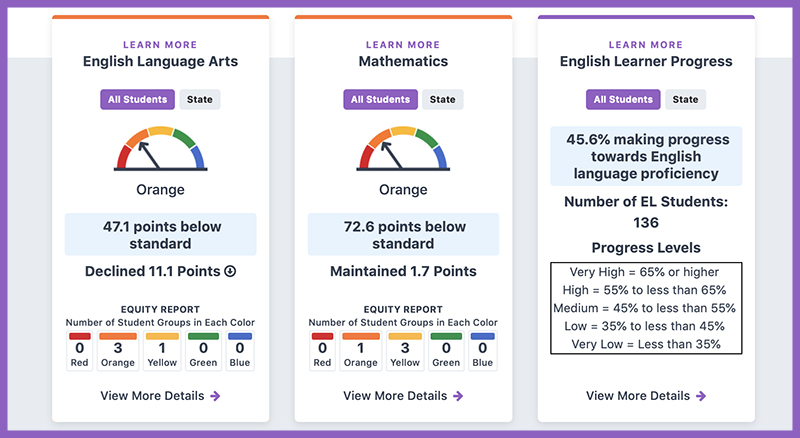

Lodestar’s academic performance on the 2019 California School Dashboard (California School Dashboard)

“We got off to a start that caused us to move from one neighborhood to another,” said Harrison. “There was a change in demographics.”

But he stressed that the school’s performance is similar to the surrounding schools in the community, and even though the school didn’t have “an opportunity to put points on the board last year,” referring to state assessments, it has improved, based on other measures.

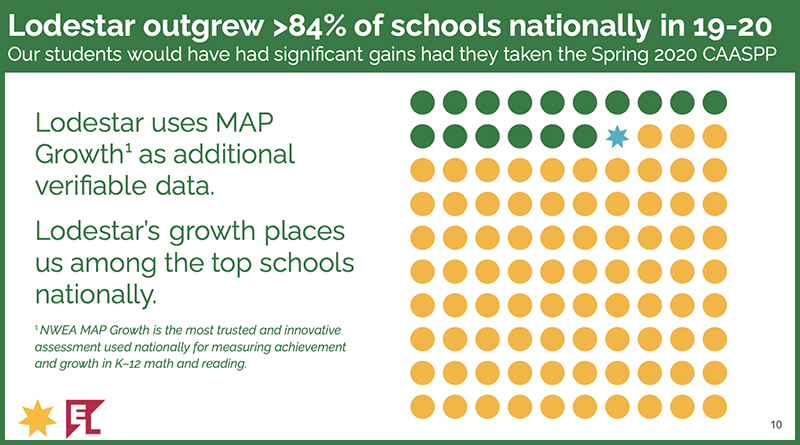

On the commonly used NWEA MAP assessment, Lodestar saw test score gains that were higher than 84 percent of schools nationally. “We felt really confident that we would have performed better” on state tests, Harrison said.

Even though state tests weren’t conducted this year, Lodestar has seen growth on other measures. (Rich Harrison)

Over 400 parents, teachers and students submitted comments to the board in favor of the school’s charter being renewed.

“My daughter has grown a lot in a short time,” wrote parent ReeSeandra Gray. “Math was her hard subject. Now it’s her strong subject and also became one of her favorite classes.”

Student Camile Mercado wrote, “If Lodestar closed, all the other students, teachers, and I wouldn’t be able to go to the amazing school anymore. So please keep the charter school open!”

Ultimately, on Nov, 18, the Oakland school board renewed Lodestar’s charter for two years.

A class of Lodestar kindergartners on Zoom (Lighthouse Community Public Schools)

Putting schools in the ‘best position’

Not all districts are delaying denials because of the pandemic. The Ross Valley School District in the Bay Area denied a renewal application for Ross Valley Charter School on Nov. 10, citing financial and governance issues. The school is rated as middle-performing, but scores well above state standards on the state report card. The school’s leaders say they will appeal to the state board for renewal.

One issue that troubles the California Charter Schools Association is that renewal requirements can vary depending on the authorizing school district. The law allowed districts flexibility to add further criteria.

“We have a bunch of school districts that can apply [the law] in a number of ways,” Macedo said. “How do we ensure that our schools are in the best position for renewal?”

During the summer, the association sent letters to LAUSD, expressing concerns about some of the requirements in the district’s charter policies and procedures and accusing the district of “acting well beyond its legal authority.”

For example, if a school moves to a new facility, the operator has to submit revisions to the district for approval. The requirement, Macedo said, “further complicates an already complex facilities acquisition process,” and likely forces them to continue sharing space with district schools, which can sometimes be untenable.

And the two middle-performing Los Angeles schools — Ánimo Legacy Charter Middle and Arts in Action Community Middle — are under additional scrutiny from the district for financial issues.

“That’s where we see the overreach,” Macedo said, adding that the law “expanded how they can close a charter school. It gives them more tools.”

Derick Lennox, a legislative advocate with the Association for California School Administrators, said the open-ended aspect of the law was “a major win for labor and lawmakers.”

But he added that charter schools also scored a victory because they can appeal at the county and state levels. “They have multiple bites at the apple,” he said.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.