As L.A. Reading Scores Rise, Roy Romer’s Tenure Offers Déjà Vu — and a Warning

Linda Jacobson | January 29, 2026

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

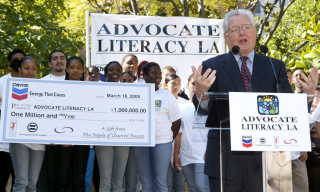

During his six years as Los Angeles Unified’s superintendent, Roy Romer made reading instruction one of his top priorities. (Jesse Grant/WireImage for JCI PR)

For the past 17 years, former Los Angeles school board members and staff have trekked to a ranch in the mountains southwest of Denver to enjoy the company of their onetime district superintendent, Roy Romer.

Wielding chainsaws, they helped the 97-year-old former Colorado governor clear out fallen timber this year to make a path for some four wheelers.

“They just enjoyed the working relationship back then, and they enjoy the friendship now,” Romer said in a recent interview.

But when they finish the day’s projects, it’s not unusual for the group to relax over wine and cheese and trade war stories about Romer’s tenure. Under his leadership, the district saw several years of steady gains in reading on both state and national tests. Fighting bureaucracy and a powerful teachers union, he required elementary schools to use Open Court, a phonics-based program that embraced what is known today as the science of reading. The district trained teachers to use it and hired reading specialists to make sure they stuck to the curriculum.

“For six years, we concentrated on that. It was the most important thing we did,” Romer said. But the teacher’s union chafed against the program’s rigid design and eventually demanded more control over the curriculum. “They didn’t want us to be screwing around in classrooms. They wanted the door shut. We forced those doors open.”

Nearly 20 years later, those stories have a new relevance as reading scores are once again on the rise. The current superintendent, Alberto Carvalho, has taken a similar, top-down approach to literacy with a program from curriculum provider Amplify. District leaders say they’ve learned from the past about the dangers of a lockstep approach to teaching reading, but some wonder whether teachers are getting the support they need.

Tackling a new curriculum is “not an easy shift, and the ongoing support is needed,” said Francisco Villegas, chief academic officer at the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, a nonprofit that manages 20 high-need schools in the district. “There are fewer dollars, and that likely will have implications for what the district is able to provide.”

The Partnership schools adopted the Amplify program Core Knowledge Language Arts in 2018-19 and began to see significant growth in English language arts on the state test. Since 2022, seven of the Partnership’s 11 elementary schools have seen double-digit increases in the percentage of students meeting or exceeding state standards. At a Harvard University conference in September, Carvalho called the Partnership a “terrific incubator” that influenced the district’s curriculum choices.

But systemwide, leaders are dipping into reserves to balance the budget and layoffs are expected. Compared to the Open Court years, training on the reading curriculum districtwide is more “hit or miss,” said Maria Nichols, president of the district’s principals union. LAUSD offers opportunities, both online and in-person, for professional development. School leaders, however, often don’t know which courses teachers have taken or whether they’re using what they’ve learned, she said. “We are PD rich and implementation poor.”

‘On the same page’

Romer’s team implemented Open Court at a time when California was pouring millions into training thousands of educators to teach reading. A $133 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education provided even more. Nearly all of the district’s 12,000 elementary school teachers participated in one-week reading institutes and many completed follow-up sessions throughout the year.

“It was phenomenal,” Nichols said. “We were treated as professionals. There was a lot of money back then.”

Former board members, among Romer’s annual visitors, said Open Court was a way to ensure all students, in an urban district where kids often change schools, would receive strong instruction. Marlene Canter, who served on the board from 2002 through 2008, said that regardless of teachers’ level of experience or the college they attended, “everybody would be on the same page.”

For some teachers, that played out literally. Many found Open Court overly prescriptive. There was a specific set of cards with letter sounds to post on the wall and a recommended U-shaped classroom layout that, according to a teacher guide, left “a large open space on the floor for whole-group and individual activities” and provided “an easy ‘walk-around’ for the teacher.” Critics viewed the literacy coaches, deployed to ensure teachers followed the curriculum, as “Open Court police” ready to catch them veering off script.

“They took my fun and creativity away,” former teacher Stuart Goldurs complained in a 2015 blog post. “I became an instructional robot.”

Ronni Ephraim, who served as Romer’s chief instructional officer, said the change upset some teachers. The district asked them to replace storybooks that had been favorites in their classrooms for years with Open Court phonics-based “readers,” workbooks and classroom libraries. Despite the objections, the district saw struggling schools improve and test score gains outpace the state.

“I don’t think top-down is bad,” Ephraim, now a consultant, said about curriculum choices. “I think the board and the superintendent have to believe in it, and then they have to make sure that everybody is prepared to teach it as designed.”

‘Big disconnect’

Critics said the program was ineffective with English learners. Over time, performance flatlined, and the district replaced Open Court with a more flexible program.

Rob Rucker is among the LAUSD teachers who worked for the district during the Open Court years and is now adjusting to Core Knowledge Language Arts. A third grade teacher at 135th Elementary School in Gardena, one of several small cities within the district’s boundaries, he said some novice teachers valued Open Court’s structure. They didn’t yet have enough experience to write lesson plans of their own.

“I actually liked Open Court,” he said. “It was very straightforward and easy for teachers to understand.”

Third grade teacher Rob Rucker has used several reading programs during his 23 years with the district. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

The Amplify program still covers the basic skills students need to decode words and recognize parts of speech. It’s also what reading experts describe as a knowledge-building curriculum. The units introduce students to early civilizations, like the Vikings in Scandinavia, and science content, such as the solar system and animal habitats.

That’s where Open Court fell short, said Nichols, with the principals’ union.

“When we tested kids, they could read beautifully,” she said, “but they couldn’t understand what they were reading.”

For a student population like LAUSD’s, with 86% living in poverty and one in five still learning English, strengthening kids’ knowledge of the world is “going to be the real game changer,” said Barbara Davidson, president of StandardsWork, a think tank, and executive director of the Knowledge Matters Campaign. Since 2015, the campaign has been a leading voice for integrating history, science and the arts into reading curriculum.

Rucker said his students were already familiar with stories like “Alice in Wonderland” and “Aladdin,” so it wasn’t hard to keep them interested in a lesson on classic fairy tales. Getting them to relate to lessons on ancient Rome has been more challenging.

According to a district spokesperson, “the goal is to ensure that every school has access to the literacy expertise and coaching capacity it needs.” But other than a two-day training from Amplify, Rucker said he hasn’t had any additional support on how to implement the program, he said. He thinks his school would benefit from an English language arts coordinator teachers could lean on when they need someone with more experience, but because of enrollment loss, many schools have lost administrative positions.

Some teachers feel Amplify is out of reach for struggling students, leading them to patch in other materials to make the material more relevant.

During a recent lesson on early American irrigation systems, Kareli Rodriguez, who teaches at Stoner Ave. Elementary School on the west side of town, used pictures and videos to help her fifth graders grasp the idea. Excitement over the Dodgers’ successful World Series run helped her pique kids’ interest in a passage on Yankees’ relief pitcher Mariano Rivera.

But it’s “not realistic,” she said, for teachers to get through a lesson in the recommended 90-minute time slot with so many students working below grade level. A district coach modeled a lesson for the teachers last school year, Rodriguez said, but she couldn’t finish it in time either.

“I think that’s a big disconnect that the district needs to understand,” she said. “It’s definitely rigorous, but most of the students are always playing catch up.”

Still, like most other schools in the district, Stoner Avenue saw improvements in reading. Fifty-two percent of fifth graders met or exceeded expectations, compared to 41% last year.

Literacy advocates hope those gains will convince leaders — as Romer did with Open Court — to stick with Amplify. “Our push is going to be to say, ‘You got to stay the course,’ ” said Yolie Flores, president and CEO of Families in Schools, a nonprofit that advocates for research-backed teaching materials. Her group breaks down the science of reading for parents so they’ll know how to talk to teachers about the curriculum and help their kids at home.

LAUSD Superintendent Alberto Carvalho read with students at Maywood Elementary School in October. (LAUSD)

District leaders gathered in October to celebrate the district’s recent improvement. Outside the auditorium at Maywood Elementary School, as students rushed back to class after lunch, Deputy Superintendent Karla Estrada took a moment to talk about lessons learned since the Open Court years, like taking feedback from teachers.

The district, she said, wants them to follow the Amplify curriculum “with integrity” while recognizing they often have to make decisions in the moment, depending on their students.

“They let me know where something is not quite what they want,” she said. “But no curriculum is going to do everything for you.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.