Beyond lessons: Tutors can help teachers build relationships with students

Dan Tracy | December 6, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

I’m a math guy. I love math, and I teach it to my preschooler every day. At a recent parent-teacher conference, his teachers told me he didn’t recognize numbers and was having a hard time counting. I pointed to the number 20, and he said, “That’s 20.” I pointed at the number 7, and he said, “That’s seven.” Then I pointed to the number 9, and he said, “That’s nine, but if you flip it upside down it could be a six.”

They had given him a test to see how well he recognized numbers, but it hadn’t taken into account the fact that he’s shy. It was a matter of quantitative data versus qualitative data.

Teachers need to know both about their students, and they gather both types of information every day in their classrooms. But there’s a way to get them even more of this essential data.

Around the country, districts and states are turning to high-impact tutoring, whether as part of the school day or afterschool, to reverse severe declines in reading and math scores since the pandemic. Tennessee has invested a lot of money and resources into this effort, and Illinois is marching down the same path.

What makes tutoring high-impact? According to the National Student Support Accelerator, it involves substantial time each week, sustained and strong relationships between students and tutors, close monitoring of student knowledge and skills alignment to school curriculum, and oversight to ensure quality interactions.

With feedback from a tutor, teacher/student conversations are more productive because the teacher can speak directly to what the student did well or struggled with during tutoring. Having a tutor’s feedback also means teachers spend less time teasing insights out of data. For example, a single note from a tutor is a much more efficient way of discovering students’ misconceptions than asking a teacher to dig through pages of data.

That’s the quantitative part. But there are also insights into how students are learning, feeling and doing — the qualitative piece — that tutors can gain insight to, and that can help teachers understand their students better.

If a tutor writes a paragraph of observations about each student at the end of every session, the teacher will have useful information to act on in real time. A note such as, “Jimmy struggles to answer questions in front of his peers, but one-on-one he gets nearly every question right” allows a teacher to respond immediately and provides a reason as to why Jimmy might be struggling. A test score doesn’t do either one.

Students who are distracted by something they don’t feel comfortable talking about in class might be willing to share it with a tutor in a small group or one-on-one setting. That information, which a teacher otherwise wouldn’t know about, can be quietly shared.

This sort of feedback is also critically important for the students who are being tutored. Imagine playing basketball, but every time you shoot, your eyes are covered up so you can’t see where your shot goes. You’d probably come to hate basketball pretty quickly, because you wouldn’t know when you were successful. When you failed, you wouldn’t know if you shot an air ball or just got an unlucky bounce off the rim.

That difference between an airball and an unlucky bounce is crucial to becoming better. An airball tells you that you need to make a large adjustment, while the bad bounce tells you you’re right on track and maybe need to adjust only slightly. Students need the same kind of feedback to help them make their academic struggles productive and begin closing in on successful solutions in math.

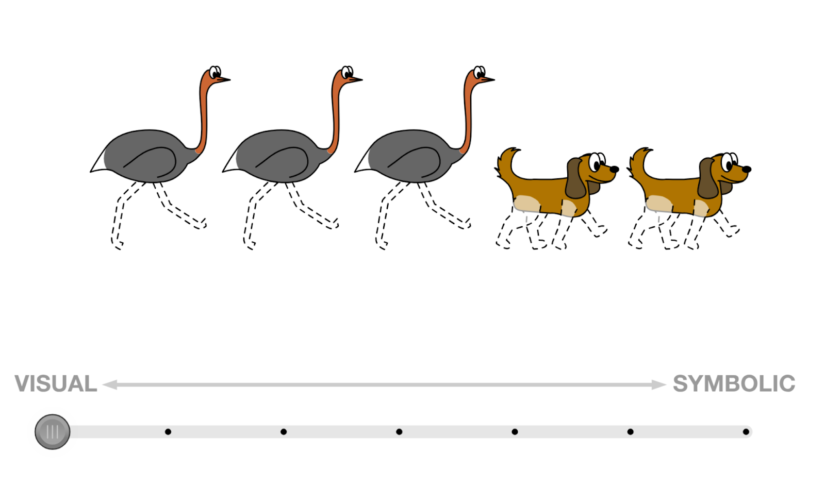

To provide that feedback, tutors need insight into how students are thinking. For example, a tutor might ask elementary school students different types of questions about this image of animals missing legs.

One of the simplest, which a tutor might ask a kindergartner, is, “How many legs are missing?” Another approach is asking a student to skip-count and get two plus two plus two plus four plus four, which is a second-grade question and answer. A student working at a third-grade level might answer with an expression: three times two plus two times four.

These answers provide insight into how the students are thinking. If they touch every leg, the tutor knows they’re counting. If they touch the animals, they’re skip-counting. This difference gives tutors valuable information that they can share with teachers, who then know what skills students need to work on. Having this clear direction allows teachers more time to focus on building rapport with students.

Tutors, armed with appropriate curriculum, can not only help students make academic progress; they can offer teachers more of the kind of data that helps them build strong relationships with their class. Students, like all humans, are motivated to work hard for someone they have a connection with, so any solution for improving academic outcomes needs to have relationships at its center.

Dan Tracy is a senior solutions strategist at Mind Education and a former high school math teacher.