COVID’s ‘complicated picture’: Mental health worse, staffing tight, enrollment frozen at nation’s schools

Kevin Mahnken | May 30, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

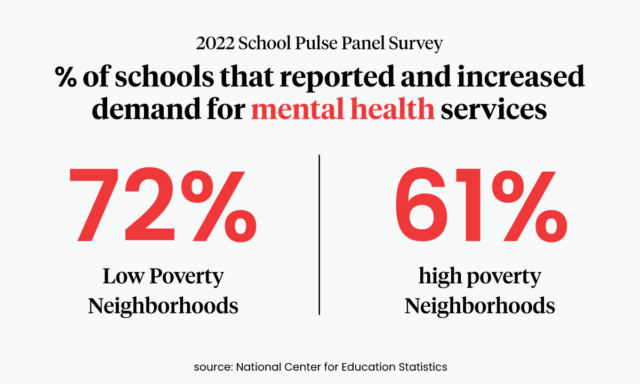

More than two-thirds of public schools saw higher percentages of their students seeking mental health services in 2022 than before the pandemic — but only a slim majority believed they were able to meet children’s heightened psychological needs, according to a federal report released Wednesday.

More than two-thirds of public schools saw higher percentages of their students seeking mental health services in 2022 than before the pandemic — but only a slim majority believed they were able to meet children’s heightened psychological needs, according to a federal report released Wednesday.

The revelation comes from The Condition of Education 2023, the latest in a series of annual digests from the National Center for Education Statistics surveying the landscape of K–12 schools. Its contents offer a nuanced account of how COVID-19 affected student experiences both inside and outside the classroom.

But the report also represents the fullest record yet of the decade preceding that once-in-a-century jolt to learning, during which K–12 spending climbed, school choice blossomed and the teaching pipeline narrowed. Compiling surveys and other data collections from over a dozen federal and international sources, the report captures how trends dating back to the middle of the Obama administration were either accelerated or untouched by the emergence of COVID.

The number of pupils enrolled in charter schools leapt from 1.8 million in 2012 to 3.7 million in 2021, when they accounted for 7 percent of all public school enrollment. Over the same period, white students shrank from a narrow majority of the total American student body to a smaller plurality. Public school revenues grew by 13 percent — compared with a 3 percent increase in student enrollment — while the dropout rate (measured as the percentage of 16–24-year-olds who haven’t earned a diploma and aren’t attending school) fell from 8.3 percent to 5.2 percent.

“The condition of education, as one might expect, is a complicated picture for the United States,” Peggy Carr, the commissioner of NCES, told reporters. “The impact of COVID on our education system gives us…an opportunity to rethink where we were.”

One bleak and well-known phenomenon that came into focus in the 2010s was the worsening mental health reality for adolescents, many of whom have reported spiraling rates of depression and anxiety. Those problems were clearly aggravated by pandemic-related school closures, which separated tens of millions of children from friends and teachers for months at a time.

In survey findings gathered last spring, leaders at 70 percent of schools said that they were faced with higher proportions of students seeking psychological and behavioral support. But only 56 percent of respondents agreed (and just 12 percent strongly agreed) that their school was able to effectively deliver that support.

Overall, 72 percent of schools said they provided mental health trauma support during the 2021–22 school year, just one of the strategies employed to help children recover from pandemic-related setbacks to learning and social-emotional development. The same percentage said they were offering remedial instruction, while three-quarters said they had implemented summer enrichment programs before the school year started.

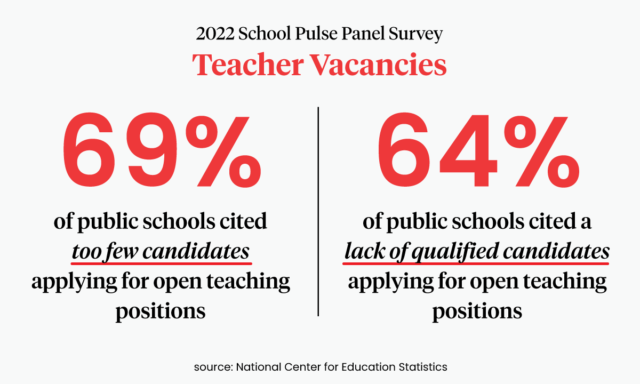

But such supplemental services were undoubtedly difficult to roll out during a time of spiking demand for school staff. Across a dozen varied academic disciplines and specialties, more schools said they had difficulty hiring for positions in 2020–21 than in 2011–12. In particular, during the first full pandemic year, substantial portions of public schools looking to hire said they had difficulty filling vacant roles in foreign languages (42 percent), special education (40 percent), physical sciences (37 percent), mathematics (32 percent), and computer science (31 percent).

Chad Aldeman, a school finance and labor market analyst, said in an email that the differences in hiring conditions between the two comparison years made it somewhat predictable that job candidates would be at a premium during the hottest jobs economy in decades.

“We were in a totally different economic environment in 2021–22 than we were a decade prior,” said Aldeman. “The ‘prime age’ employment rate was very low [during the Great Recession], and the unemployment rate was 8.3 percent in January 2012, compared to 4 percent in January 2022. It would be surprising if schools were bucking these trends and not struggling to hire in this environment.”

At the same time, however, a breakdown in the teacher training pipeline might have contributed to the apparent pandemic-era shortages in teachers and other school staff. Between the 2012–13 and 2019–20 school years, the report showed, the number of candidates enrolled in traditional teacher preparation programs shrank by 30 percent; the number of people completing such programs declined by 28 percent, from 161,000 to 116,100, during that interval.

On the heels of those developments, public school enrollment counts were profoundly changed by the impact of COVID and the switch to online learning.

Longer-term trends show a steady increase in total students, from 49.5 million to 50.8 million, between fall 2010 and fall 2019; but over the next academic year, the entirety of that decade-long growth — 3 percent of all public school students — vanished as public school enrollment fell back to 49.4 million. (Notably, persistent growth in the charter school sector continued during the early stages of the pandemic, with charter school enrollment swelling by 7 percent between fall 2019 and fall 2020.)

As earlier reporting has indicated, drops in head counts were heavily concentrated among the youngest students. While 54 percent of three- and four-year-olds were enrolled in school in 2019, just 50 percent were in 2021. The percentage of five-year-olds in school also fell, from 91 percent to 86 percent, during those two years.

Thomas Dee, an economist at Stanford who has carefully examined state enrollment figures during the pandemic, said the statistics were “a potent reminder” of the educational harms suffered since March 2020.

“The sustained declines in pre-K and kindergarten enrollment are important,” Dee wrote in an email. “Many of our youngest learners are missing important early learning opportunities, and it will be years before most age into conventional testing windows that will provide some indication of what this means for their learning.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.