Critics call ‘consumer reports’ of school curriculum slow to adapt to science of reading

Linda Jacobson | May 20, 2024

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

When Tami Morrison, a teacher and mom from outside Youngstown, Ohio, discovered Superkids, she thought she’d found the perfect way to help young children learn to read.

Kids like her daughter Clara, a second grader, glommed on to its rich characters; she’s especially fond of Lily, who wears her black hair in a short bob and has a collection of plush toy lions. Fellow teachers, meanwhile, like that it “hits everything” students need to be strong readers.

“It slowly builds, introducing more and more sounds, and then it jumps right into blending those sounds into little words,” Morrison said. At least two independent studies link the program to “significant positive” results.

Tami Morrison, a second grade teacher, whose daughter Clara learned to read with the Superkids program, objected when the state initially didn’t include the curriculum on an approved reading list. (Tami Morrison)

But that winning combo initially wasn’t enough for Ohio’s education department to put Superkids on its list of approved K-5 reading materials. Morrison homed in on a likely culprit: EdReports, a nonprofit that for nine years has operated as a kind of “Consumer Reports” for the multi-billion dollar K-12 publishing industry. At the time, Ohio leaders approved only programs that won the organization’s coveted green rating. Superkids earned a more modest yellow.

“How EdReports can be the sole basis of this process is astounding,” Morrison, also a local school board member, wrote to the state. Ohio trains teachers in the science of reading, she said, but “this list takes us three steps backward.”

Ohio ultimately relented after Zaner-Bloser, which publishes Superkids, appealed. Temporary as it was, the episode demonstrated the outsize power of EdReports in the world of high-stakes curriculum decisions — a power that has come under increasing scrutiny as more parents embrace the phonics-laden science of reading. Critics of the nonprofit say it has continued to award green ratings to reading programs that might still accommodate balanced literacy — a discredited philosophy in which teachers encourage kids to learn to read by surrounding them with books— and has slapped effective programs with yellow ratings.

In interviews with LA School Report, EdReports officials say they’ve gotten the message.

Starting in June, its reviews of early reading materials will reflect a fuller embrace of the science of reading. “Phonics and fluency are now non-negotiables” for a green rating, said Janna Chan, EdReports’ chief external affairs officer.

Reviewers will also verify that materials no longer use “three-cueing” — a practice associated with balanced literacy that encourages students to identify unfamiliar words by picking up clues from text or pictures. Since 2021, at least 10 states have banned the practice.

An internal memo sent to EdReports staff in February and obtained by LA School Report acknowledged growing doubts about the organization’s credibility as states pass new reading laws. CEO Eric Hirsch wrote that the organization is “most vulnerable to criticism around our reviews” of comprehensive English language arts programs called basals or “big box” curricula — programs that some have attacked for being “bloated” and giving lip service to the science of reading. Hirsch wrote the memo in response to a Forbes article that critiqued the organization and highlighted newer groups providing alternatives to its reviews.

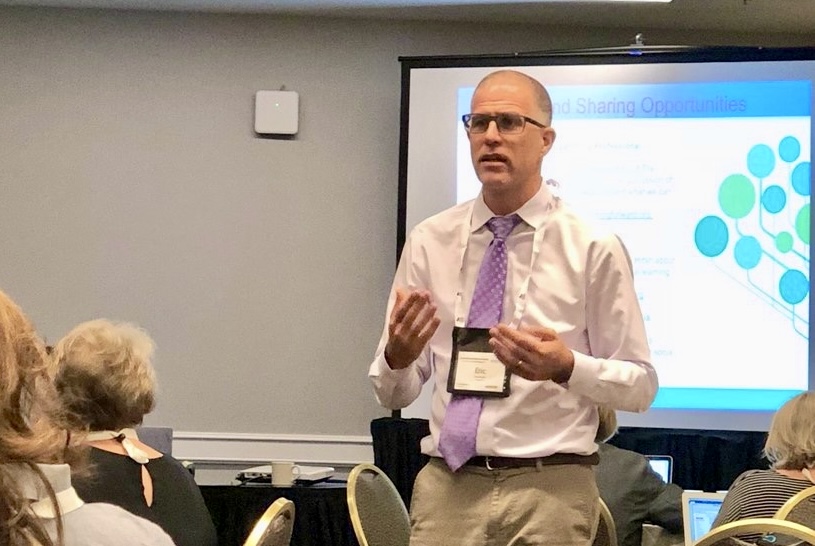

Eric Hirsch founded EdReports in 2015 to point districts to curriculum materials aligned to the Common Core. (EdReports)

EdReports contracts with a network of over 600 reviewers, many of them current or former teachers who earn up to nearly $3,000 per review. Working in teams of five for an average of four to six months, they determine if curriculum products meet standards and are easy for teachers and students to use.

Evidence of the organization’s considerable influence isn’t hard to find. A 74 analysis of GovSpend, a data service that stores recordings of public meetings, reveals that since January 2021, EdReports has been mentioned over 100 times during school board meetings. District leaders and staff frequently invoke its ratings when making budget recommendations.

The “end-all, be-all for curriculum review” is how Bill Hesford, an assistant superintendent in the Bayfield, Colorado, district described the organization during a January discussion of a new math program.

That same month, T.C. Wall, assistant superintendent of the Bolivar, Missouri, schools, assured her board that all reading programs up for consideration had earned the organization’s highest rating.

“We’re starting with quality stuff,” she said.

Financially, there’s much at stake for both districts and curriculum companies. Fueled by a one-time infusion of federal relief funds, school systems spent roughly $19 billion on curriculum in the 2021-22 school year alone. Due to the time and expense such reviews require, districts typically wait as long as six years before revamping their offerings.

Pressure to ‘conform’

For many publishers, EdReports’s green stamp of approval is a valuable marketing tool they trumpet in press releases.

Others lost trust in its reviews years ago.

Collaborative Classroom, a curriculum provider, publishes four literacy programs based on the science of reading used by hundreds of districts. One of them underwent four reviews in three years because, in Hirsch’s view, new features warranted a fresh examination. But the process left Kelly Stuart, the publisher’s president and CEO, exhausted and disillusioned.

“We play in this world as a nonprofit,” she said. “But if we were a for-profit company, there would be a tremendous amount of pressure on us to conform and meet all green.”

In a world so contentious its seminal debates are called “wars,” critics have been particularly vocal — including those who initially welcomed EdReports.

Karen Vaites, a literacy expert and advocate, once led marketing efforts for Open Up Resources, a nonprofit that offers free curriculum materials to districts. Declaring that “excellence is now easy to find,” she was among the first to point educators to EdReports in 2018.

Karen Vaites, left, a literacy expert, visited a kindergarten class in Tennessee’s Lauderdale County Schools as part of a school tour with the Knowledge Matters Campaign, a nonprofit that reviews curriculum to determine if it builds students’ background knowledge. (Courtesy of Karen Vaites)

In recent years, her views have taken a 180.

“EdReports is no longer an effective guidepost,” said Vaites, who founded the Curriculum Insight Project in January to essentially compete with the organization. One of its first projects is to review Bookworms, an Open Up Resources program that earned a yellow from EdReports, but has research showing effectiveness and won praise from districts that use it.

Vaites said she no longer has a financial relationship with Open Up Resources. But having once been an EdReports “fangirl,” she said she feels “doubly obliged to let people know that they need to look beyond” the site.

https://twitter.com/karenvaites/status/1027758528218509312?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1027758528218509312%7Ctwgr%5Ef3ccd73b75fbd68a71e0b4975e39ad38aa005a66%7Ctwcon%5Es1_c10&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.the74million.org%2Farticle%2Fcritics-call-consumer-reports-of-school-curriculum-slow-to-adapt-to-science-of-reading%2F

Hirsch declined to address her specific criticisms, but said he and his team plan to gather feedback from researchers, as well as district and state leaders, to respond to critics’ concerns. By the end of the summer, the organization expects to update guidelines for all three of the content areas it reviews — English language arts, math and science — and apply them to next year’s reports.

Hirsch told LA School Report the pivot is in keeping with its mission as an organization geared toward — and staffed by — teachers.

“You’re not a great teacher if you can’t reflect on practice,” he said.

‘No counterbalance’

With backing from major foundations, Hirsch founded EdReports in 2015 to help guide districts toward materials that satisfied the then-relatively new Common Core standards, a set of guidelines in math and language arts that most states still follow. In an attempt to tap into the booming market, many publishers touted their products as “Common Core-aligned” even when their commitments were tenuous at best. Experts say a third-party reviewer was sorely needed.

“Some publishers had a vice grip on the whole curriculum thing,” said Kareem Weaver, an Oakland literacy advocate featured in The Right to Read, a documentary about the push to provide low-income and minority students with high-quality reading instruction. “Before EdReports, there was no counterbalance to publishers’ claims of being ‘high-quality.’ ”

Now with an $11.5 million annual budget, Hirsch called the organization “amazingly transparent,” without “taking a dime from publishers.” But Weaver thinks EdReports would have a greater impact if its reviews factored in evidence of effectiveness.

“Don’t just treat kids like guinea pigs,” he said. “Parents have to know if their kid is actually going to get the things they need in regular classroom instruction.”

Hirsch responded that solid, independent evidence of a specific curriculum’s effectiveness is rare. When it does exist, publishers typically offer it in response to reviews. But he conceded that EdReports could make the information easier to find.

‘Bloated’ materials

Evidence is also important to state leaders, who increasingly expect districts to adopt reading programs based on research. But some experts say publishers are responding to new mandates by “overstuffing” their products — adding structured, phonics-based lessons without removing the older ones.

Vaites points to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Into Reading, one of the three programs approved as part of NYC Reads — a two-year effort to overhaul literacy instruction in the nation’s largest school district. EdReports gave it a green rating, despite complaints about its overabundance of units, lessons and worksheets.

“As a novice teacher, you’re going to get overwhelmed when you see four pages that go along with one lesson,” said April Rose, an instructional coach at P.S. 132Q in Queens, who works with the United Federation of Teachers to support staff transitioning to the program. With such wide offerings, some teachers struggle to find assignments for students that match the standards they’re trying to teach, she said, or hop from one skill to the next without giving students deep practice.

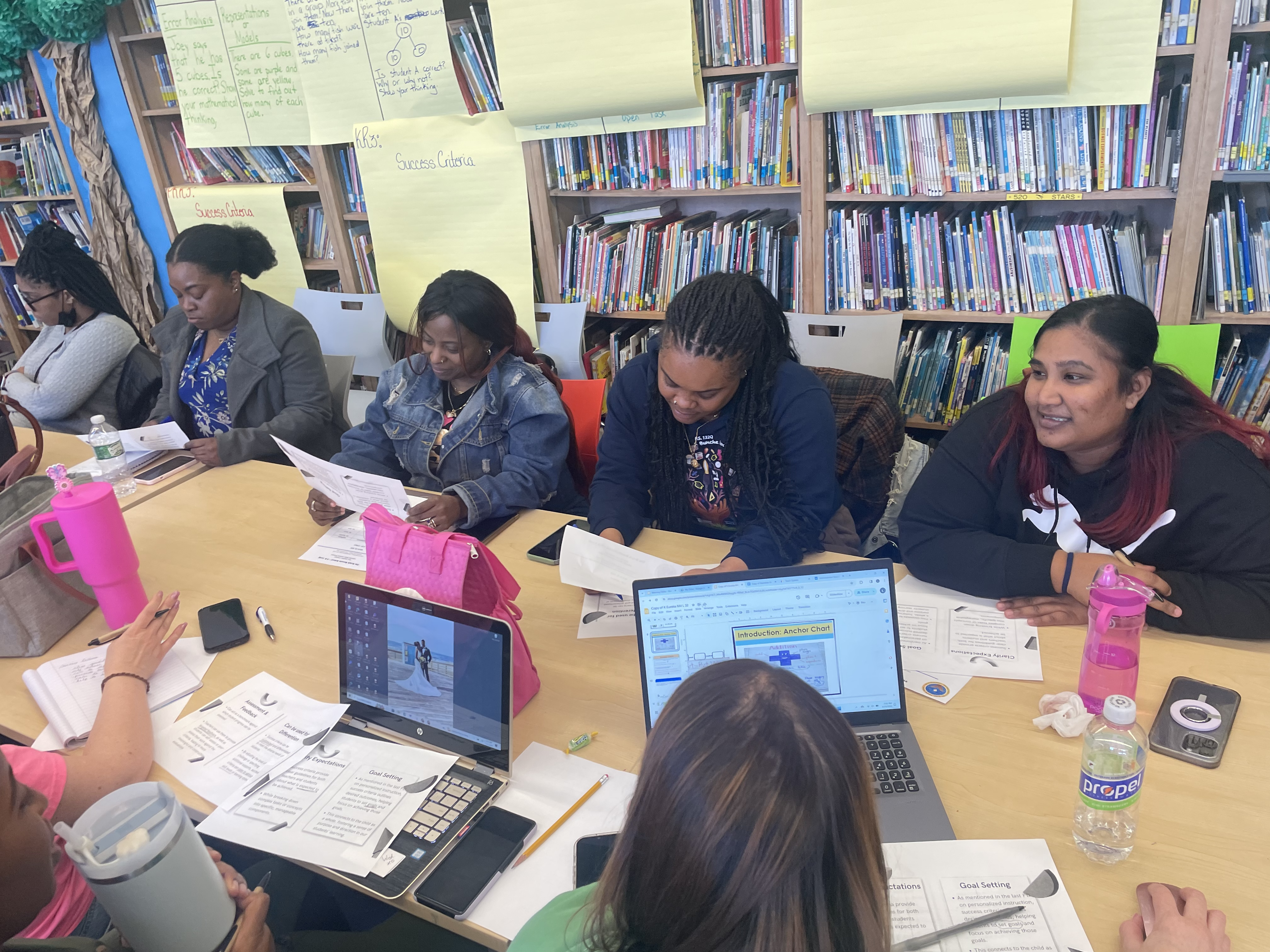

New York City teachers implementing Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Into Reading curriculum met at a UFT Teacher Center for training. The program is one of three the district is using as part of its NYC Reads initiative. (United Federation of Teachers)

Jim O’Neill, a general manager at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, said Into Reading is designed to let teachers “grow while teaching with the program.” The broad range of lessons and activities, he added, is also intended to support students at multiple levels in one classroom.

“Coming out of the pandemic, there are two things we have — students with different needs, but also new teachers who are just beginning to teach reading,” he said. “Having carefully crafted lesson plans can help them get up and going with the right resources for the right students at the right time.”

Hirsch acknowledged bloat is a problem, but said publishers are reluctant to remove features some teachers prefer.

He suggested that districts adopting a new curriculum view EdReports as just a starting point — and follow up with adequate training and support for teachers.

Timothy Shanahan, an emeritus professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, agreed. “School districts rely too much on these external reviews without a clear understanding of what they tell you and what they do not,” he said. “They need to give a close look at the programs themselves.”

Disclosure: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, the Overdeck Family Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to EdReports and to LA School Report’s parent company The 74.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.