Despite slight reprieve, districts still struggle to find teachers, staff

Linda Jacobson | October 25, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Roberta Campbell, a substitute in the Henry County district, worked with a small group of elementary school students. (Henry County Schools)

Post-pandemic staffing challenges have eased up slightly this fall, but many school leaders report that they still have crucial vacancies to fill.

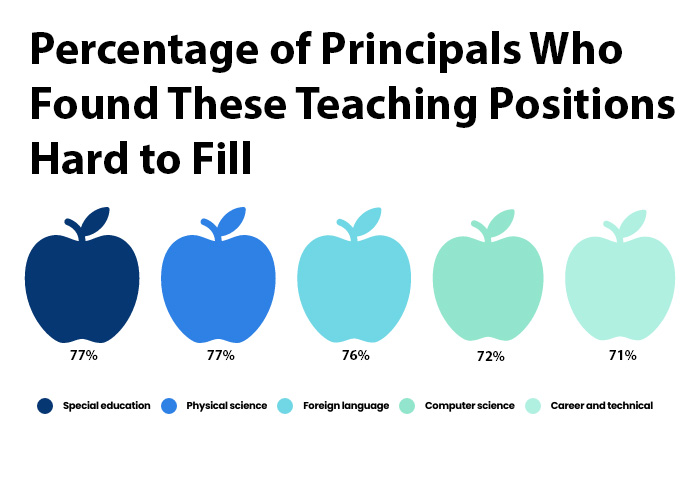

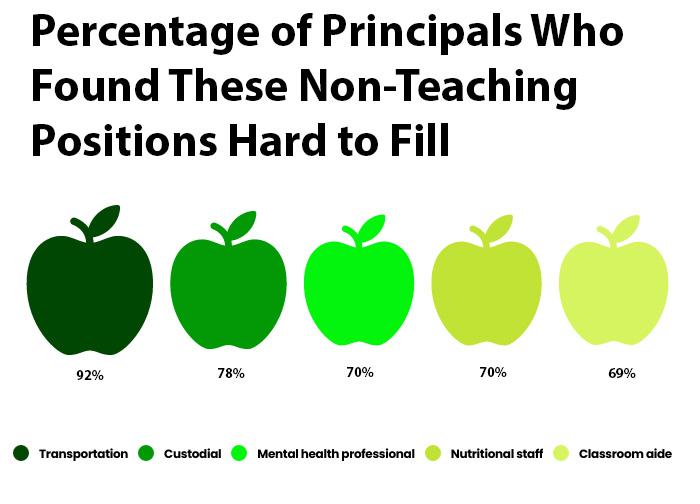

The latest federal data on the public education workforce, released Tuesday, shows 45% of leaders said they were understaffed as the new school year began. That’s down from just over half last year. But the vast majority of schools say they’re still struggling to hire enough teachers and other staff, including classroom aides, bus drivers and mental health professionals.

In the latest results from the School Pulse Panel — a National Center for Education Statistics survey — over 1,300 administrators reported having the hardest time hiring enough elementary and special education teachers as well as classroom aides and custodial staff.

National Center for Education Statistics

“You used to have thousands of applicants for every one vacancy. You don’t have that anymore,” said Mary Elizabeth Davis, superintendent of the Henry County Schools, outside Atlanta. Her team tried to attract candidates this year at local fairs, festivals and civic events, but still has about 100 vacancies districtwide. “We actually had recruiting tables at our high school graduations.”

While conditions vary from district to district, the overall uptick in teacher turnover since the pandemic has forced district and school leaders to rely on substitutes, contract with virtual teaching companies and offer attractive incentives to lure new hires. Meanwhile, temporary federal relief funds offered the chance to create new positions to help with academic recovery efforts, but there haven’t always been enough candidates to fill those roles. Whether job seekers are leaving for other districts or finding positions outside of education, they clearly have the upper hand in this current market.

“It is harder to hire than it was pre-pandemic,” said Chad Aldeman, a researcher who focuses on the teacher job market. “The labor force participation rate is really high, unemployment is really low and basically anyone of working age who wants a job can find it.”

Recent Bureau of Labor Statistics data confirms that what many have called a crisis in teacher employment is slightly less severe this year. Compared to last fall, there’s a 2% increase in the number of public school employees — or about 150,000 more. But districts have to work harder to win over those sought-after candidates and get creative when they can’t.

To fill the gaps, the Henry district has hired more teachers from overseas and attracted 25 new college graduates through a “retention scholarship.” In exchange for a two-year commitment, the district covers the cost of their teaching credential program.

Henry has also joined the growing number of districts across the country using virtual teaching companies. While a substitute or aide supervises students in the classroom, licensed teachers provide instruction remotely — sometimes from several states away. Davis tells parents the remote arrangement is far better than using a substitute. Without it, she added, their children might not be able to take Spanish III or A.P. Calculus.

“This is what kids are going to need to be able to do in college, so we actually see this as a good thing,” she said.

‘Double-edged sword’

Even districts with traditionally stable workforces have had to take unusual measures to ensure students have teachers. The 5,600-student Rush-Henrietta Central School District, south of Rochester, New York, typically loses no more than five teachers a year. This past summer, Superintendent Barbara Mullen saw 28 leave, mostly to neighboring districts that offer more money. She organized a job fair — something the district has never had to do.

“We issued a press release. I went on the news,” she said. “People were walking in off the street.”

When that effort only filled 12 positions, she gave educators an unexpected pay raise — a minimum of $1,600 for veteran teachers and up to $5,000 for newer teachers. Non-teaching staff also received raises. With federal relief funds expiring next year, she said staff members recognize there could be leaner years ahead.

“I needed to send a strategic message that compensation is important and working conditions are important,” she said.

Like many districts, Rush-Henrietta uses a grow-your-own approach to address staff shortages. Parents can work as interns in the district’s Cub Care Zone afterschool program and then take the exam to become a teaching assistant.

National Center for Education Statistics

Other districts offer an accelerated route to a teaching job to classroom aides, professionals changing careers and even those without four-year degrees. States were relaxing teacher training requirements long before the pandemic, but have expanded those policies to address the current emergency.

But such actions can also leave holes to fill.

Kimberly Winterbottom, principal of Marley Middle School in Glen Burnie, Maryland, said her state offers so many new pathways to become a teacher that it can be harder to find candidates still willing to work as substitutes and classroom assistants — the staff members schools have been relying on to give students extra support.

“It’s like a double-edged sword,” she said.

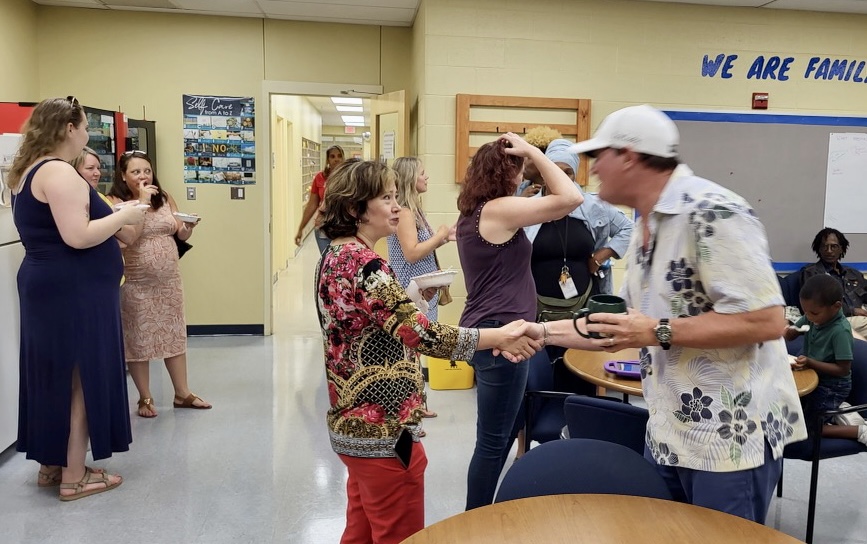

Larry Ascione, assistant principal at Marley Middle School in Maryland, welcomed Andrea Del Rio, a career-changer-turned Spanish teacher at an ice cream social for new employees. (Courtesy of Kimberly Winterbottom)

Her school had 35 open positions this year. She was able to fill them, but candidates, she said, weighed offers between multiple districts and have grown choosy about which grade levels they want to teach.

“The candidate holds the cards,” she said.

As the numbers show, however, leaders say this fall feels like more of a return to earlier years when it was tough to find teachers in areas such as science and special education, but shortages didn’t overwhelm the system. In several cases last year, districts even had to close some schools because there weren’t enough teachers.

Davis, in Henry County, said one sign of progress is that 89% of substitute positions have been filled this fall, compared to 40% last year.

“Part of the retention challenge was exhaustion. People were doing multiple people’s jobs,” she said. “We’ve not arrived, but we’re on a path to people being able to do their job most of the day and to start feeling effective at it. That will turn the corner for us.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.