‘Education’s long COVID’: New data shows recovery stalled for most students

Linda Jacobson | July 12, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

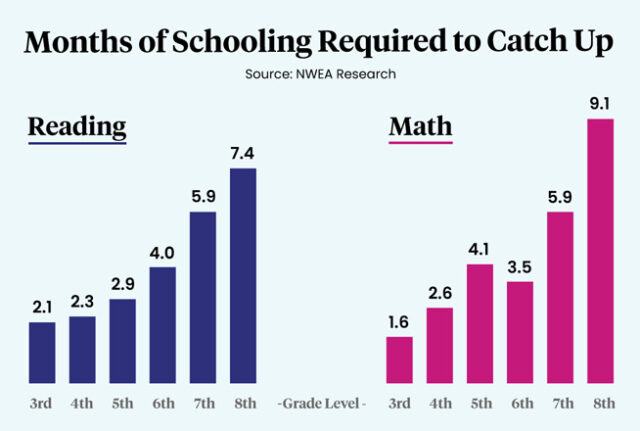

The graph shows how many months of school students need to reach pre-pandemic levels in reading and math. (NWEA/Eamonn Fitzmaurice/LA School Report)

Pandemic recovery has essentially stalled for most of the nation’s students, new data shows, and upper elementary and middle school students actually lost ground this year in reading and math.

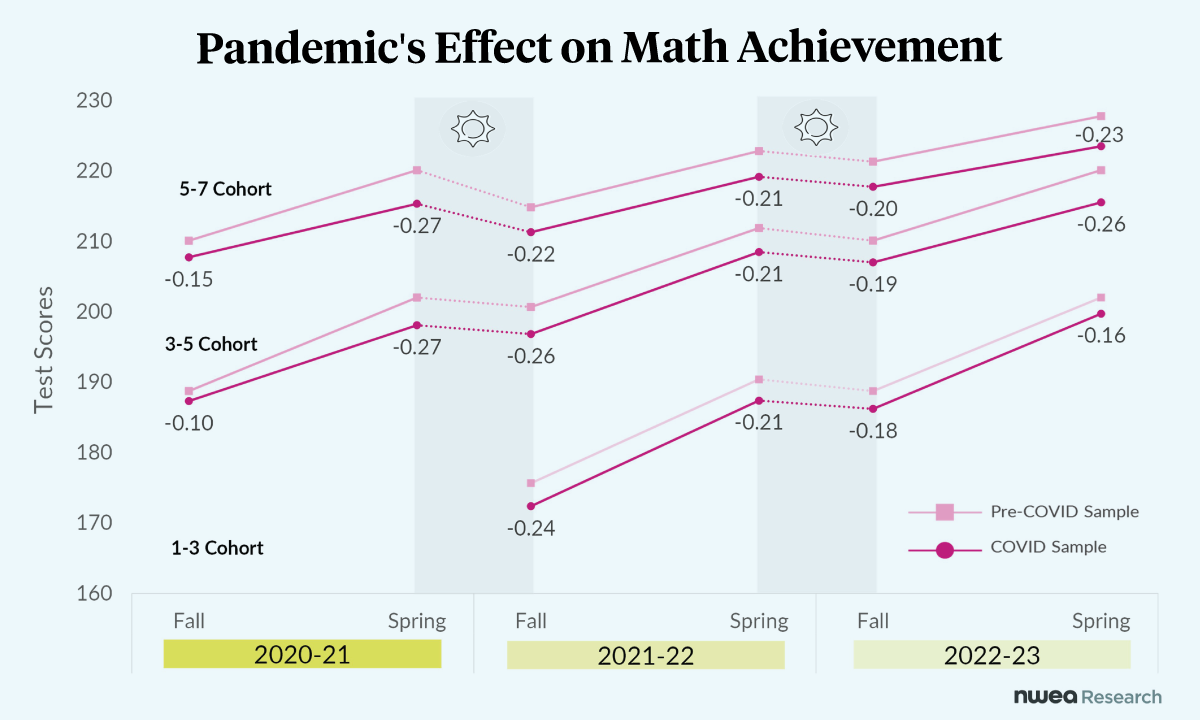

On average, students need four more months in school to catch up to pre-pandemic levels, according to the results from NWEA, a K-12 assessment provider. This fall’s ninth graders need far more — roughly a full extra school year.

“There’s still a pretty big distance between the COVID and the pre-COVID trends,” said Karyn Lewis, director of NWEA’s Center for School and Student Progress. “We’re not doing anything to shrink that distance.”

Within the grim results, however, there was a spark of hope for the youngest students. First- through third-graders were the only students to make above-average gains. But that progress only returns them to “an already significantly inequitable state of academic achievement,” researchers said.

They described the data from 6.7 million students who took the organization’s MAP Growth tests last school year as “education’s long COVID.” The results come just weeks after the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress revealed sharp declines in reading and math for the nation’s 13-year-olds, continuing a downward trend that began a decade ago.

Students who experienced the greatest setbacks during the pandemic — the intended beneficiaries of billions of dollars in federal aid — have the most ground to make up. But time is running out to use the remaining relief funds for tutoring, expanded summer school programs and other recovery efforts. The extended emergency, Lewis said, has kept her up at night.

“I very much worry that these results will fan the flames of ‘Schools didn’t use these dollars wisely,’ and I don’t think that’s the case at all,” she said, noting that many are using proven teaching methods for students below grade level. “It’s just not enough. The dosage is not in line with the magnitude of the crisis.”

But Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research, is more critical of efforts to reach students who have fallen the furthest behind. The data, he said, lines up with CALDER’s research on 12 districts showing low participation in optional interventions like tutoring and summer programs.

“You’d never know that there had been a pandemic,” he said. He acknowledged the views of those who argue there’s too much emphasis on test scores, but added that such assessments still predict the types of courses students take and whether they’re on track to go to college. “The education ecosystem is not healthy.”

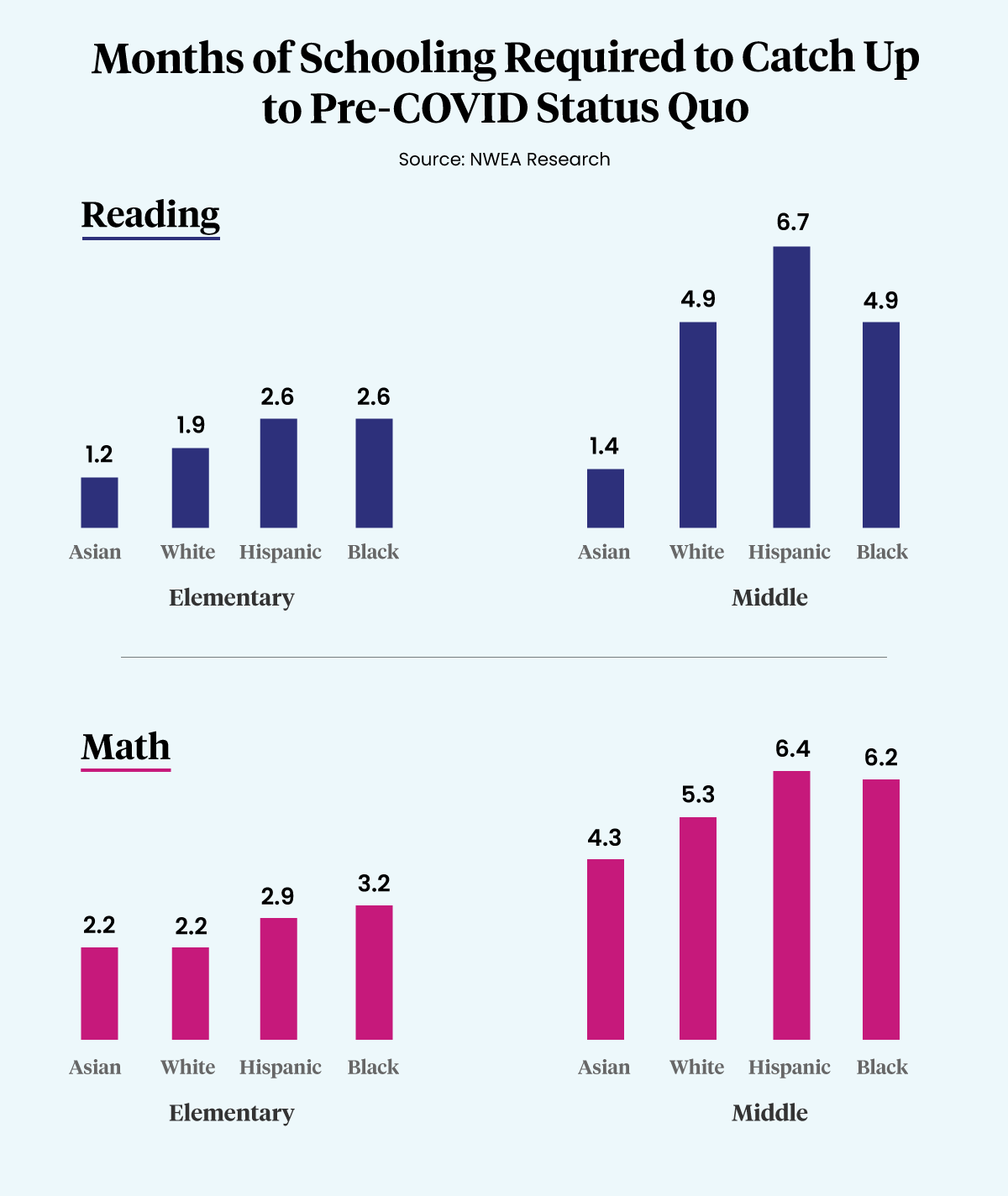

The NWEA results show students who finished eighth grade this year need an additional 7.4 months of learning to reach pre-pandemic levels in reading and 9.1 months in math. Black and Hispanic students need even more extra instruction to get there, the data shows.

The graphs show how many more months of school students in each racial group need to reach pre-pandemic performance in reading and math. (NWEA/Eamonn Fitzmaurice/LA School Report)

Lewis compared pandemic learning loss to tornado damage. A hammer and nails, she said, might be sufficient to repair a lost shingle or a loose shutter. But if a garage is flattened or the roof is gone “a hammer and nail is not going to cut it,” she said.

To Kimberly Radostits, last year’s Illinois Teacher of the Year, that’s an apt metaphor. Her house was leveled by a twister in 2015. She spent 18 months rebuilding and sees a parallel between recovering from that literal destruction and schools’ efforts to put the pandemic behind them.

“We’re back to normal, but everybody is just tired,” she said. “I do think there’s a burnout that comes with that.”

The NWEA results, she said, point to the need for more efforts to support ninth graders — like the Hawks Take Flight mentoring program she co-founded in the Oregon Community Unit School District.

The program typically serves 15 students who struggle with missed assignments, poor grades and behavior problems in eighth grade. But Radostits said she would double that number if she could find additional teachers willing to volunteer as mentors. To fill some of the gaps this fall, the high school will replace one elective with an extra “skill-building class” in math and English for students who need it.

“We need to be more flexible with our scheduling than ever before,” Radostits said.

But some districts that have tried to add school days or reconfigure the traditional calendar have faced stiff opposition. The Los Angeles Unified School District last year had to move extra learning days to holiday breaks after the teachers union fought a plan to embed them throughout the year. And an effort to implement a year-round calendar in the Richmond, Virginia, schools — to prevent further summer learning loss — was ultimately adopted at just one school after parents, teachers and board members pushed back.

Researchers studying the pace of recovery worry that schools aren’t always straightforward with parents about the long-term effects of the pandemic.

“Schools never say to parents, ‘Hey I’m really worried that given these test scores or attendance patterns, I’m not sure that your kid’s going to go to college,’ ” Goldhaber said.

Oregon High School’s mentoring program begins “planting a seed” in eighth grade with parents whose children could benefit from the program, Radostits said. Using an early warning system that shows parents a dashboard of their child’s grades, attendance, discipline record and work completion often makes the difference.

“We can click a button that will fade every other student’s name on this database except for the one you are looking at,” she said. “That’s a powerful visual for parents.”

Some advocates say parents still get mixed messages from schools. Sonya Thomas, executive director of Nashville Propel, pointed to recent comments from district leaders about third graders’ performance on Tennessee’s reading test. Nashville Director of Schools Adrienne Battle said that just because students didn’t reach proficiency — required to advance to fourth grade — didn’t mean they failed or couldn’t read.

“To me, that message was toxic,” Thomas said. “We have a literacy crisis that has gone on for decades.”

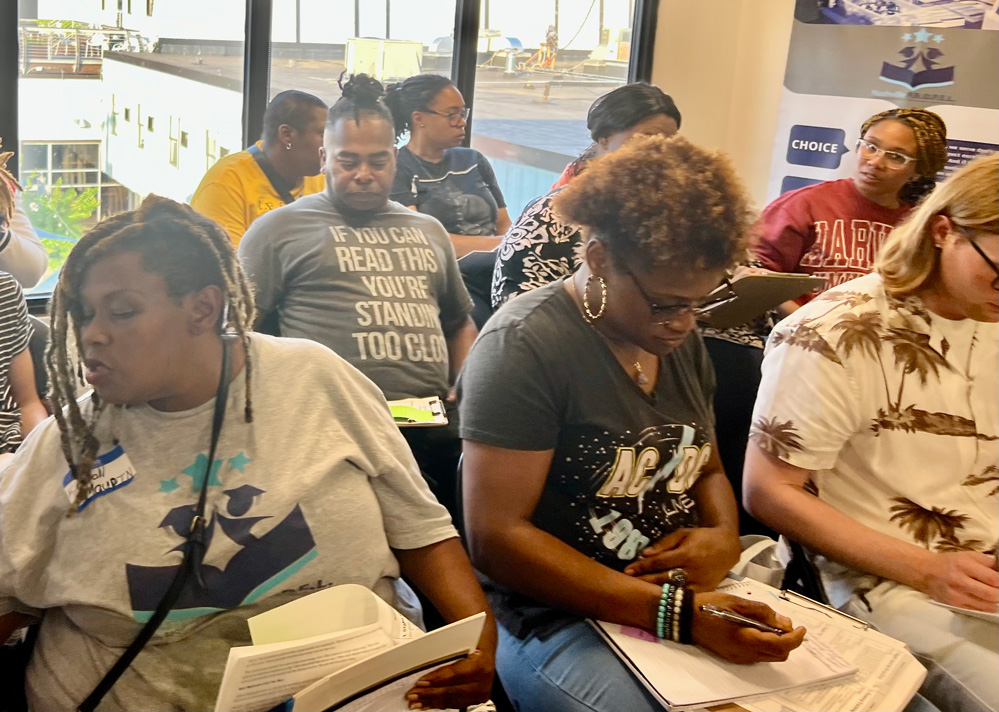

The organization is holding a six-week literacy institute this summer to help parents better understand the components of reading and their children’s performance.

Parents are learning more about how to track their children’s progress in reading at Nashville Propel’s summer literacy institute. (Nashville Propel)

‘It was shocking’

The fact that the gap between pre- and post-pandemic achievement for fourth through eighth graders grew larger this year instead of smaller was a hard pill to swallow, said NWEA’s Lewis.

“There was a hope that a lot of lessons learned in 21-22 could be applied in 22-23,” she said. “We actually see the opposite. It was shocking to us.”

In a summary of the results, she and Megan Kuhfeld, an NWEA senior research scientist, said the backslide was likely due to ongoing “behavioral, academic and staffing challenges.” Many districts are still reporting high chronic absenteeism rates.

They attribute the encouraging signs in first- through third-grades to younger students’ tendency to learn faster. Their scores were 4% above pre-COVID levels in reading and 2% above in math — largely echoing mid-year data released earlier this year from Amplify, a curriculum provider.

Lewis said perhaps “word got out” that younger students were missing basic skills and “that’s where schools have leaned in.”

Some districts have also heeded warnings from researchers about the most effective types of recovery efforts. In the 4,700-student William Penn School District, outside Philadelphia, students attending summer school get 90 minutes each of reading and math instruction followed by more traditional camp activities in the afternoon.

“With rising third graders, we’re making sure they’ve mastered everything they were supposed to learn in second grade,” said Ed Dunn, curriculum supervisor. He still gets emails from parents asking if spots are open. About 1,100 students are enrolled this summer, up from 750 last year.

William Penn teacher Lisa Myles reads to students during summer school. Over 1,100 students are enrolled this summer, up from around 750 last year. (William Penn School District)

The district considered offering students voluntary, online tutoring during the school year, but instead opted for organizing small groups for extra help during class.

“We want to make the most of the actual school day,” Dunn said. “Our students need too much support to just leave it to chance.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.