Educators Beware: As budget cuts loom, now is NOT the time to quit your job

Katherine Silberstein and Marguerite Roza | June 22, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Eamonn Fitzmaurice/LA School Report

For several years there have been lots of available jobs in school districts. Employees could take a year off and, with all the openings, take comfort in the knowledge that districts would always be hiring if and when they wanted to come back.

But those days are over. Thinking of quitting in the next few months or years? Think twice. Because odds are you’ll have a tough time finding another education job in the next several years.

That’s because the job market for teachers is about to do a U-turn with the hiring spree of the last few years set to stall out before coming to a screeching halt at the start of the 2024 school year.

In some areas, the reversal has already started and districts are pulling down their “help wanted” signs. Portland and Auburn, Maine issued a hiring freeze this spring. Hartford, San Francisco, and Baltimore County are eliminating unfilled positions. Fort Worth and Seattle are already doing layoffs. And this is just the beginning. Last month, at an education finance training we conducted at Georgetown University, we heard from dozens of school officials from all over the country whose districts were already making similar moves or are poised to in the next year.

What’s behind the flip? In the last few years, the hiring bonanza has been fueled by a flood of federal pandemic relief funds (ESSER). Districts across the country used that money to add staff that they wouldn’t have been able to afford otherwise. Now, that funding is set to disappear by the fall of 2024, which means districts are paying for more employees than they can afford.

To make matters worse, during the same time period, districts have been losing students. That means that state and local dollars (which tend to be driven by enrollment counts) are unlikely to make up the gap.

Staffing-enrollment mismatch spells big financial trouble ahead

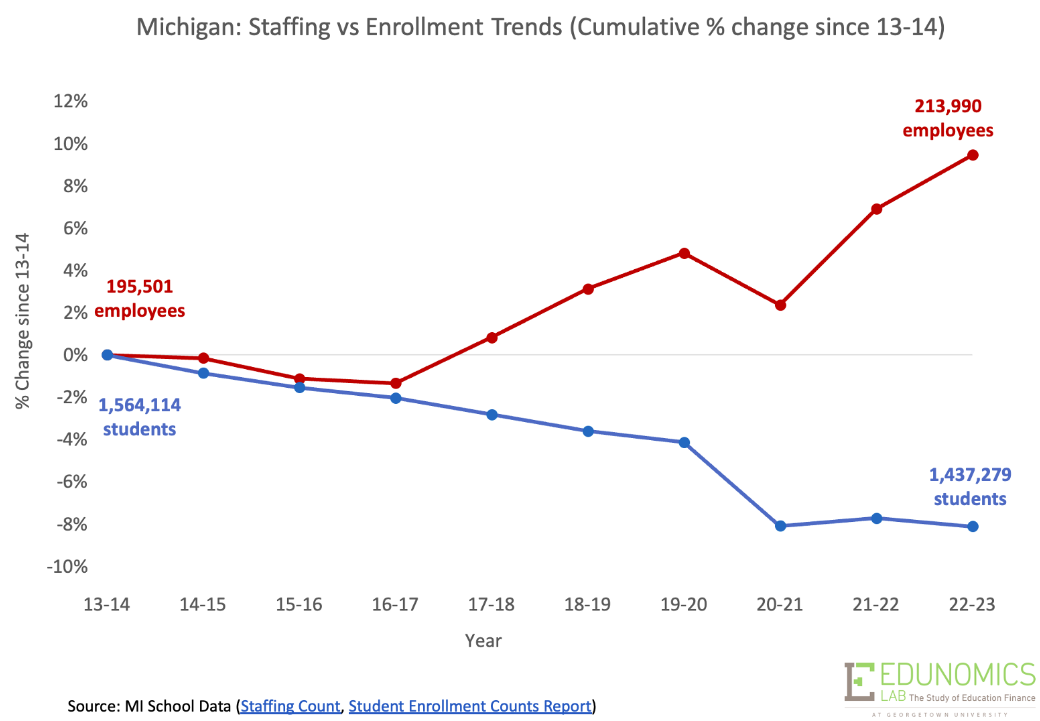

With all these extra staff in schools and declining enrollment, a rightsizing is coming. These trends aren’t just afflicting large urban districts, either. Rather, in states where we have the data, the patterns are playing out statewide. Over the last decade, Michigan districts have grown staffing rolls by 9%, all while student enrollment fell by 8%.

In Connecticut, staffing is up by 8%, while enrollment is down 7%. Same trend in Pennsylvania. Even in Washington State, where there’s been enrollment growth of 3%, it won’t be enough to sustain the 20% jump in staffing over the same time period.

True, some states, like Texas and Florida, are seeing school enrollments grow. So, job seekers might find more opportunities there (though both states offer notoriously low teacher salaries). And just as staffing and enrollment patterns can vary by state, same goes for districts within states, too. Even so, when job openings are down statewide, it means the available candidates are vying for a smaller number of positions. (States or districts wanting to better understand their own staffing and enrollment patterns can use this template.)

ESSER hangover

Federal COVID relief funds fed a hiring habit that can’t be sustained. The dreaded fiscal cliff predicted to hit when the ESSER spigot dries up was once treated as some abstract future threat. But we’re now watching that threat play out in real time as districts work to finalize next year’s budgets this month. It’s all right there in the budget financials released by schools this spring.

With last week’s debt limit deal, it’s clear that more federal funding won’t come to districts’ rescue. And states aren’t likely to fill the hole either, as many of their revenue forecasts are sliding downward, too.

Georgia recently reported a one-year drop of 16.5% in net tax collections. Massachusetts had a whopping 31% year-over-year decline in tax revenue. And California’s state revenue forecast just keeps getting gloomier.

For educators in high-demand roles, like math, science or special education, there will still be jobs. But for others, it’s likely to get much tougher as districts start to shrink their labor force to align with their new enrollment numbers.

The public discourse about widespread teacher shortages may be confusing to some, particularly when the data show we’ve just finished a period of staffing up our schools. In most regions, however, the new reality is this: Those seeking jobs in schools will soon be facing a job market quite different than what we’ve seen for several years.The upside for districts that are hiring? When there are fewer jobs and more job seekers, districts can afford to be choosier, and the quality of new hires rises.