Exclusive: Despite K-2 reading gains, results flat for 3rd grade ‘COVID kids’

Linda Jacobson | March 6, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

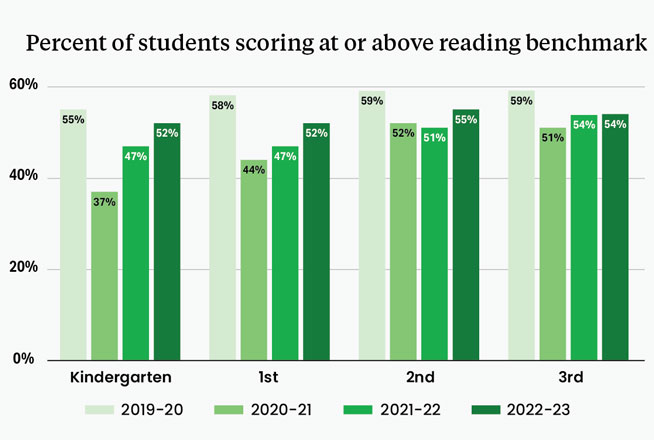

New mid-year data from Amplify shows the percentage of students in K-2 on track in reading continues to approach pre-pandemic levels. (Amplify/The 74)

The percentage of third graders on track in reading hasn’t budged since this time last year, new data shows — a reminder of the literacy setbacks experienced by kindergartners when schools shut down in 2020.

Even so, the test’s administrators are interpreting the flatline at 54% as good news. Paul Gazzerro, director of data analysis at curriculum provider Amplify, said it’s likely that third graders would have fallen even further behind without efforts like tutoring and additional group instruction.

“It looks as if nothing happened, but the reality is I would’ve suspected that things could’ve gotten worse,” he said. “These are students in many cases that are missing very tangible skills. They may even be grade levels behind.”

The results come amid brighter news for younger students. The mid-year data, which reflects the performance of about 300,000 students across 43 states, show that more K-2 students are reading on grade level compared with 2022 — a sign that literacy skills overall continue to slowly inch back to pre-COVID levels.

“The actual pandemic effect seems to be lessening,” Gazzerro said.

Amplify’s latest early literacy snapshot reflects a far less disruptive year than the last one. Schools aren’t dealing with frequent quarantines as they did during last year’s Omicron wave. In addition, many states and districts are in the midst of revamping how they teach reading and are using federal relief funds to purchase new curriculum and train teachers.

In some cases, states are taking the lead. Tennessee has put $100 million toward teacher training and ensuring districts have a phonics-based reading curriculum to match. And the Texas Education Agency will soon publish a list of approved materials to follow up a state law requiring districts to teach phonics.

At The 74’s request, Burbio, a data company, scanned 6,500 districts’ plans for spending American Rescue Plan funds. Over 3,800 report an emphasis on literacy, more than 4,100 mention reading and over 2,586 note ELA or English language arts. A smaller number, 530, specifically included phonics, and 258 identified science of reading in their plans.

It’s too soon to know whether these developments have had a measurable impact on students’ skills, but they’re “not hurting, that’s for sure,” said Susan Lambert, Amplify’s chief academic officer for elementary humanities.

The return to a more predictable schedule has contributed to the growth as well, she added.

“We can make progress when kids are in the classroom,” she said. “The data shows that.”

Amplify uses an assessment called Dynamic Indicators of Basic Literacy Skills, or DIBELS, to test student progress toward learning letter sounds and blends, recognizing sight words and gaining speed and accuracy.

Students in K-2 haven’t caught up to peers who were in those grades just before COVID hit. But they did make more progress between fall and winter than students did last year. That’s especially true for the youngest students. In 2021-22, the percentage of kindergartners on track grew 15 points over that time period. This year, it grew 19 percentage points.

‘Can’t spell Harry or Potter’

For teachers, it’s rewarding to see their students leap from identifying one or two sounds in a word to accurately writing complete sentences.

JoLynn Aldinger, who teaches first grade in the West Ada School District, near Boise, Idaho, said her students’ growth over the past five months makes her want to “do cartwheels” in the classroom.

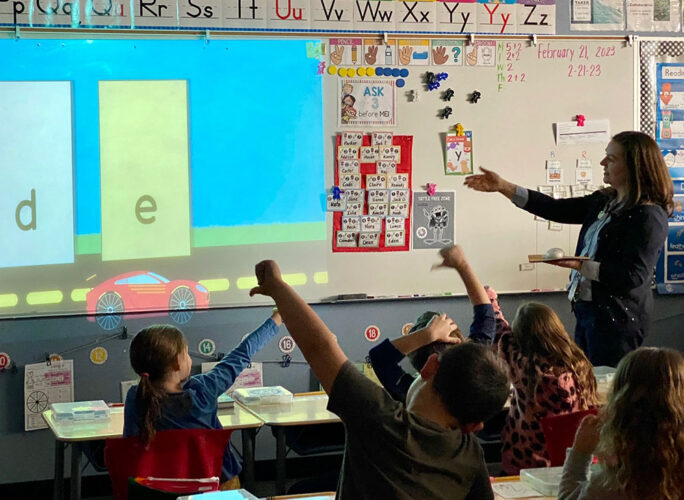

JoLynn Aldinger’s first graders give a thumbs down to indicate when they see a nonsense word. (Courtesy of JoLynn Aldinger)

A 25-year veteran teacher, she used to emphasize stories and comprehension over phonics. But when she had a 7-year-old in her class who took longer than her peers to learn letter sounds, Aldinger set off on her own quest to learn more about the so-called “science of reading.”

‘I thought, ‘I have a master’s degree in reading. I should know how to teach reading,’ ” she said. “I knew what phonics was but I didn’t understand how explicit it needed to be.”

She applied for a grant from her school’s PTA, which paid $1,275 for her to receive training in methods often used with students who have dyslexia. The techniques, like pounding out syllables on their desks and spending extra time on letter blends, benefit even her strongest readers, she said.

“I would have kids walk in my classroom who have read ‘Harry Potter,’ but they can’t spell Harry or Potter,” she said.

Now she shows off her students’ improvement to anyone who will listen. And she asks other teachers if they’ve listened to “Sold a Story,” a podcast about how whole language or “balanced” literacy came to dominate reading instruction in U.S. schools. Research shows the approach, which focuses more on access to books and using pictures or other clues to guess words, can leave students without the phonics skills to become strong readers.

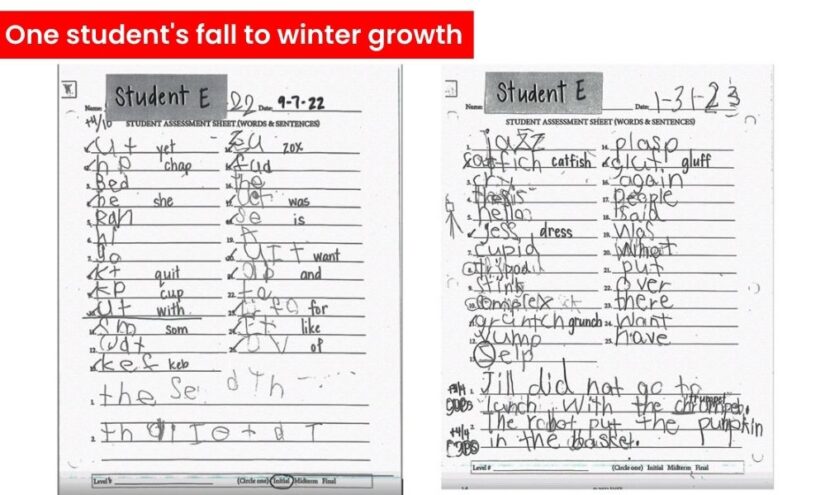

In the fall, one of JoLynn Aldinger’s first graders at Galileo STEM Academy in Eagle, Idaho, could barely write a word or a complete sentence. By the end of January, he made substantial progress. (Courtesy of JoLynn Aldinger)

‘Our COVID kids’

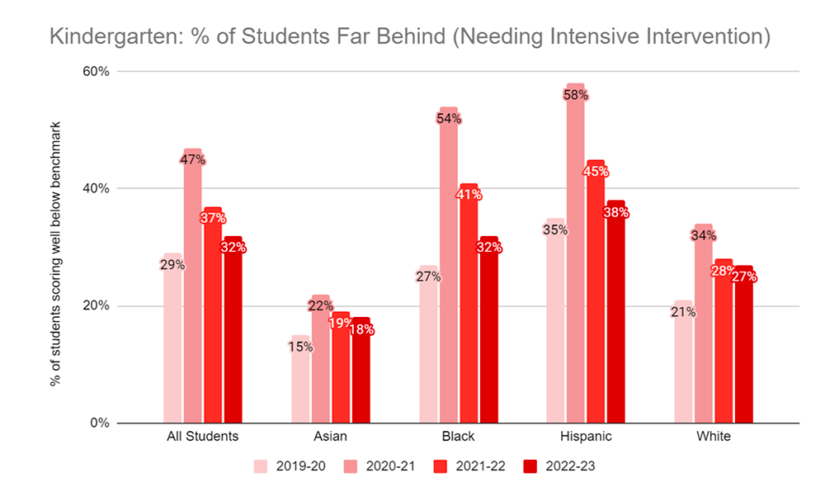

The Amplify data includes other indicators that trends are headed in the right direction. Racial gaps in reading — which grew larger during the pandemic — have narrowed slightly. And between Hispanic and white students, the disparities are even smaller than before COVID.

Since 2019-20, the gap between Hispanic and white kindergartners needing “intensive” support, for example, has fallen from 14 to 11 percentage points. And in third grade, the gap between Hispanic and white students on track dropped from 13 to 8 percentage points over the same time period. For Black students, it remains at 19 percentage points.

The racial gap in reading between Hispanic and white students has narrowed among kindergartners, compared with the 2019-20 school year. (Amplify)

Third grade, Lambert said, is when foundational skills “are supposed to come together” for students so they can learn from what they’re reading.

That’s what Jean Hesson, elementary supervisor for the Sumner County Schools in Tennessee, hopes to see this spring when this year’s third graders take the state test.

“These are our COVID kids,” she said. Even though the district has adopted a strong curriculum, “ultimately you have 20 wildcards sitting in front of you. You have to know where your kids are.”

As in districts statewide, Sumner teachers are now required to use phonics-based instruction. The district adopted the Wit and Wisdom curriculum for reading about history, science and other topics. It added the Fundations program for phonics and Geodes — a set of books that tie content and literacy skills together.

“The pictures don’t lend themselves to guessing words,” Hesson said. Students “truly have to decode and use their skills.”

Almost 45% of last year’s third graders met or exceeded English language arts standards — an increase over pre-pandemic scores. Hesson is hoping that trend continues.

“If we had not had high-quality materials, teachers would have been teaching in a million different directions,” she said. “I can’t imagine the gaps that we would have created.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.