Four top takeaways from the school research of new Biden adviser Kirabo Jackson

Kevin Mahnken | August 21, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Largely constrained from enacting its national K–12 agenda, the Biden administration nevertheless made waves in the education world earlier this month by appointing economist Kirabo Jackson to a seat on its Council of Economic Advisers.

Jackson, a labor economist and professor at Northwestern University, is far from a household name, but his work has made a significant impact on education policy over the last decade. In particular, he has been the most outspoken of a group of researchers arguing that higher spending on education can meaningfully lift students’ prospects — a position at odds with the widely held political consensus of the 1980s and ‘90s.

The Council is a three-member body that advises the president on economic affairs. While it shares that responsibility somewhat with other offices, including the Treasury Department and the National Economic Council, its influence as a kind of think tank within the Executive Branch has proven to be considerable. Since its founding in 1946, four former CEA heads have gone on to chair the Federal Reserve, including former Chairwoman Janet Yellen, who now serves as President Biden’s treasury secretary.

The panel will face its share of fiscal and workforce problems over the next few years, principally the question of how to further suppress inflation without leading to job losses. But Jackson’s appointment signals that Biden’s team is keeping its eye on the president’s K–12 priorities. Those priorities have met with only limited success through the first three years of Biden’s term; an increase in funding for school counselors last fall made some progress on his campaign pledge to double the presence of mental health practitioners in schools, but a corresponding commitment to triple the budget of Title I has failed to materialize.

Whether Jackson’s appointment, which is not subject to Senate confirmation, will jumpstart the White House’s education work is unclear. But it will bring an expert on education finance into even greater prominence, and likely put a spotlight on some of the issues he’s worked on throughout his career.

Here’s a quick guide to four studies that have helped build Jackson’s reputation.

1. Money really does matter

For decades, researchers have debated whether directing more resources to schools (i.e., spending more to raise salaries, hire more teachers, or buy better curricula) actually results in better academic results. Many economists — pointing to substantial growth in education spending alongside modest improvement in standardized test scores — have voiced doubts.

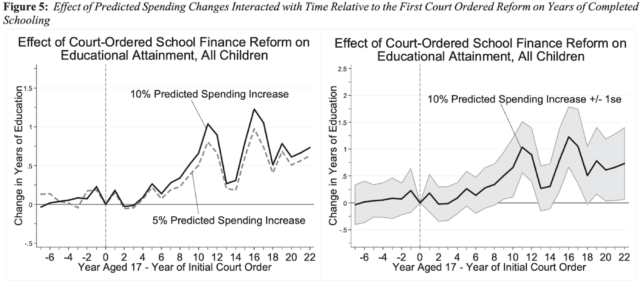

But a 2015 study co-authored by Jackson, American University Professor Claudia Persico, and University of California, Berkeley, Professor Rucker Johnson has helped shift the views of the policy community to the opposite view. Analyzing the impact of court-mandated education finance reforms on children born between 1955 and 1985, the team discovered that boosting education funding by 10 percent annually for each of a student’s 12 years of public school produced the learning equivalent of an extra .27 years of schooling. The effects carried into adulthood as well; affected students were 3.67 percent less likely to be poor, and they received wages that were 7.25 percent higher than otherwise.

The paper was not the first or last to emphasize the importance of money to kids’ academic success. But as much as any over the last 10 years, it has helped shape the conversation around one of the most contested areas of American education.

2. Schools affect more than test scores

Another of Jackson’s fascinations has been the range of child outcomes that schools contribute to outside of purely academic ones. That perspective is somewhat unusual in the economics of education, where empiricists tend to focus on metrics that are most available and legible: grades and test scores.

In a 2016 paper, Jackson went further, investigating the role of classroom teachers in developing students’ non-cognitive skills. Those traits — such as motivation and self-control — are thought to be critical, if hard-to-measure, prerequisites to adult activities like finishing college and holding down a job. Relying on a set of proxies for non-cognitive skills, including suspension rates and absences, the study examined how ninth-grade teachers both fostered non-cognitive growth and test score trajectories over time.

In the end, he found that teachers sometimes generated significantly different effects on skills than they did test performance. What’s more, their influence on non-testing outcomes was associated with students’ high school graduation and plans for college-going “above and beyond” their impact on test scores; in fact, combining testing and non-testing measures of teacher quality was more than twice as predictive of student success as using scores alone. Particularly as some in the education world turn away from a perceived over-use of assessment, the findings demonstrate the depth of what’s still unknown about how schools help kids thrive.

3. Some kids get more out of great schools

Good schools are good for everyone, right? The building blocks of a superior learning environment, from great teachers to supportive peer relationships, lift all boats.

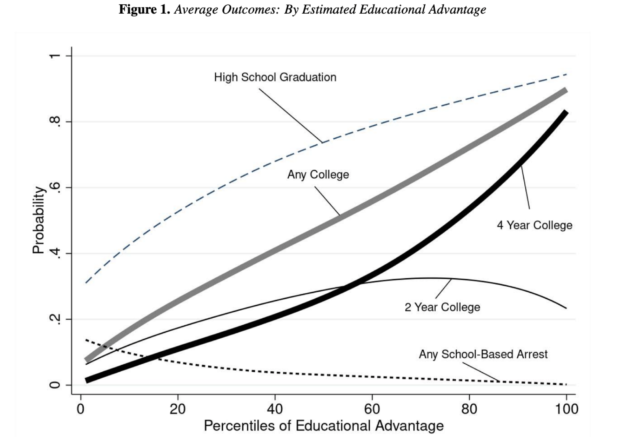

While those sentiments are true by and large, a paper from last yearadds a bit of nuance. Co-authored by Jackson, Shanette Porter, John Easton, and Sebastián Kiguel, it looked at thousands of students in Chicago high schools, where inequality in educational opportunity is extraordinarily high. In total, the team found, less-advantaged students — those with lower eighth-grade test scores, more disciplinary incidents, and from lower-income homes — benefit the most from attending highly effective schools that improve both test scores and non-cognitive skills.

Not only were those potentially at-risk kids more likely to graduate high school, they were also arrested less and saw better odds of enrolling in college than otherwise similar peers. In addition, the holistic index of school effectiveness used by Jackson and his co-authors was found to be more predictive of later-life success than simply using test scores alone.

4. Single sex schools might not be the way

In one of his earliest works as a solo researcher, Jackson examined the effects of students being assigned to single-sex schools in Trinidad and Tobago. Proponents of sex-sorted schooling often point to the developmental and social differences between boys and girls, who reach maturity at different ages.

By exploiting the quasi-randomness of the algorithm that assigned students, however, Jackson was able to directly analyze the effects of attending all-boys and all-girls academies. In the end, he found, most students saw no academic advantage from being so assigned — though participants who expressed the strongest preference for that form of education (predominantly girls) did see some bump in learning. Strikingly, girls enrolled at single-sex schools also took fewer science courses on average.

Read Next

-

With Costs Rising and Relief Money Gone, LAUSD Taps Reserves to Pay for New Budget

-

LAUSD Agrees to Issue $500 Million in Bonds to Settle Sexual Abuse Claims

-

Looming California Budget Changes Threaten Black Students, Study Says

-

COMMENTARY

California Students Have Fallen Behind, These Two Solutions Can Help

-

Florida Teacher: Juneteenth Explores the Oft-Avoided Side of U.S. History

-

COMMENTARY

Last School Year Was the Hottest on Record. How Do We Protect Students?

-

L.A. Families Are Mostly Satisfied With Their Schools, Survey Says

-

COMMENTARY

How My California Middle School Uses Glyphs to Teach English Learners to Read