House vote sets stage for approval of sweeping pandemic relief package, with $126 billion for reopening schools, learning loss

Linda Jacobson | March 9, 2021

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi conducts a news conference on the on the COVID-19 relief bill, the American Rescue Plan Act on March 9. (Getty Images)

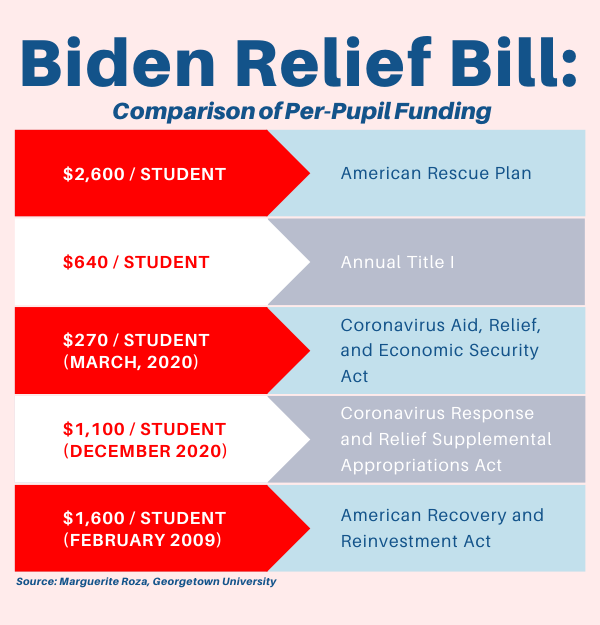

The House is soon expected to pass what President Joe Biden calls an “urgently needed” funding package that sends $126 billion to K-12 schools — almost twice as much provided in COVID-19 relief last year and significantly more than they received to recover from the Great Recession.

The vote, expected by Wednesday, sets the stage for Biden to sign the American Rescue Plan later this week.

Following Senate approval of the plan after a marathon session ending Saturday, Education Secretary Miguel Cardona called the package “a huge step in helping get students back into the classroom.” But Republicans attacked the bill, which passed through the majority-led budget reconciliation process without a single GOP vote. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said the plan advanced in a “haphazard” and “less rigorous” way than the five relief bills enacted last year.

Biden’s plan provides $2,600 per student, more than double the amount in December’s relief package. And it would send $46 billion more to K-12 schools than they received under the 2009 stimulus bill, meant to make up for lost state revenues during the Great Recession. The size of Biden’s relief package demonstrates the magnitude of the challenge states face in reopening schools and helping students recover from a year of remote learning. Districts would have broad flexibility in how to spend the K-12 funds. But the new plan carries more restrictions than last year’s relief bills, intended to ensure that states and districts focus on helping students catch up on instruction they’ve missed. Republicans failed to make the receipt of funds contingent on in-person learning, but experts said passage of the plan should speed up the process.

Once they receive relief funds, schools would have to develop and publicize their plans for ramping up in-person learning within 30 days. That amendment, sponsored by New Hampshire Democrat Sen. Maggie Hassan, passed 51 to 48.

“Combined with President Biden’s directive that health officials prioritize school employee vaccinations, there should be no reason for public schools to delay reopening, except in communities with very high COVID infection rates,” said Thomas Toch, the director of FutureEd, a think tank at Georgetown University.

For months, teachers unions, education advocacy groups and Democrats have argued that schools needed a funding package of at least this size to reopen schools with the proper safety measures in place.

‘Prescriptive and targeted’

State education agencies would hold on to about $15 billion from the total allotted for K-12, while the rest would be distributed to districts.

The bill prohibits states from using the new pot of federal money as an excuse to cut state education spending in their fiscal year 2022 and 2023 budgets, but allows the education secretary to waive that requirement.

The final package no longer includes a special “hardest hit education fund” for governors to oversee — part of Biden’s original proposal —but it does contain a “maintenance of equity” provision to protect high-poverty districts from budget cuts.

“This is an attempt to ensure states don’t repeat the same mistake [from] last recession, where they made cuts in state funds that had greater impacts on higher-poverty districts,” said Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab, also at Georgetown.

The equity provision, she added, demonstrates the importance of the federal rule, which took effect last year, that districts post on state report cards how much they spend per student at each school.

For students with disabilities, who haven’t received many of the services they’re entitled to since schools closed, the bill provides an additional $2.6 billion in grants for K-12 students as well as $200 million for preschoolers and $250 million for infants and toddlers.

Under the bell, both states and districts would need to address learning loss. Preliminary data shows that students are as much as a year behind in math and significantly off track in reading as a result of the pandemic. The declines are greatest among Black and Hispanic students. The federal bill mandates states to reserve 5 percent and districts to spend 20 percent of their funding for this purpose — a requirement that is “even more prescriptive and targeted” than the relief bill passed in December, Roza noted.

The bill provides about $520 per student specifically for learning loss, but some researchers estimate it would cost five times that much per year to provide the tutoring and other support students needed to catch up.

With the funds districts are just now beginning to receive from the t December bill, states have to report how they’re measuring declines in students’ learning and what they’re doing to combat it.

The new “package asks a lot of [states],” she said. “They’ll need to up their game with spending on summer activities, learning loss, enrichment.”

Many states are considering — or are already implementing — new programs on learning recovery. To support those efforts, the federal bill would require state education departments to set aside 2.5 percent for educational technology, 1 percent for afterschool programs and 1 percent for summer school, including enrichment activities.

“This means every state must use part of their education funding to increase summer slots for kids,” Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut said during a recent webinar, calling the requirement a “big win for kids.” Biden previously suggested, during a town hall gathering in February, that some districts might treat summer like another semester.

Another win, according to many advocacy groups, was a voice vote to set aside $800 million for homeless students — the one display of bipartisanship during Saturday’s session.

“They are dealing with the challenges of virtual learning,” said Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, a co-sponsor of the amendment. “These kids are worrying about where they’re going to sleep at night.”

Democrat Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, another sponsor, added that roughly 420,000 children “are potentially unidentified and not connected with a school system.”

The funding provides eight times the amount that states currently receive through the Education for Homeless Children and Youths program, also known as the McKinney-Vento Act. The funding allows schools to “really target support to homeless kids for a wide range of needs,’ said Barbara Duffield, executive director of SchoolHouse Connection, an advocacy group focusing on homeless students.

Another provision added to the bill recommends that community schools — in which schools serve as hubs for a range of social services — be used for mental health support such as in-school therapy for students.

Cardona in a ‘convening role’

While the bill requires states and districts to allocate some of the money in specific ways, experts don’t expect the Department of Education to use the funding to push for specific policy changes, as it did during the Obama administration.

With the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, states received $80 billion for K-12. That package included the Race to the Top grant program, which former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan used as a financial incentive to get states to adopt the Common Core standards and evaluate teachers based on student test scores.

“That gave the federal government a much more prominent role in K-12 education policy than it had had in the past,” Toch said.

But states and districts still might look to the Department of Education “for ideas on how to spend so much money,” said Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “And I suspect the Biden folks will be happy to play a convening and technical assistance role — nudging their state and local partners in certain directions, with a gentle touch.”

Provisions on child care, cutting child poverty

Additional provisions outside of the education section of the bill include:

- $1 billion for Head Start

- Almost $40 billion for child care

- An increase in the Child Tax Credit from $2,000 to $3,000, and $3,600 for children under 6. The bill would apply the credit to families with very low or no income and extend it to cover 17-year-olds.

- $7.2 billion for E-Rate, an internet discount program for schools that would provide more devices and hotspots for students.

- An extension of the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer program though the summer months and as long as the pandemic continues. The program provides food benefits to families whose children qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.