How is the largest school police force in the nation keeping LA’s children safe?

Mike Szymanski | October 24, 2016

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Every day, the news headlines make Police Chief Steven K. Zipperman aware of something more he has to do to help 664,000 children feel safe coming to school.

Every day, the news headlines make Police Chief Steven K. Zipperman aware of something more he has to do to help 664,000 children feel safe coming to school.

Chief Zipperman cradles the responsibility of keeping LA Unified’s students safe, as well as its 60,000 employees.

And that’s a tall order in a today’s world, with social media reports of scary clowns frightening kids, rumors of immigration agents raiding schools and seemingly credible terrorist threats.

“The unusual activities that occurred over this past summer were unprecedented,” Zipperman said in an exclusive interview in his office at the Los Angeles School Police Department just a few blocks from the LA Unified Beaudry Avenue headquarters in downtown Los Angeles. “The acts of terrorism worldwide and nationally at the Orlando nightclub and the controversial police shootings and the post-Ferguson reaction and Black Lives Matter demonstrations all rekindled concerns that we need to focus on our relationships with the community and revisit what we are doing.”

• Read more: 9 things you didn’t know about the school police who guard your children

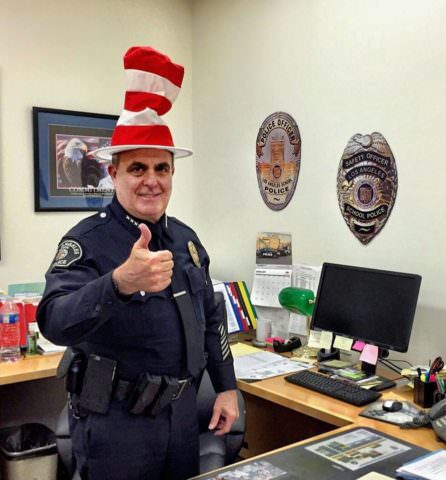

Chief Steven K. Zipperman in his office.

Now in his fifth year on the job, Zipperman acknowledges it is a tougher time than ever to make the children of Los Angeles feel comfortable with uniformed officers. In a rare candid interview, Chief Zipperman detailed some of the things that his office does that few people know about, and some of the behind-the-scenes preparations that make him feel confident that his department can handle any emergency at LA schools.

“The issue of police-community relations is on the top of our list,” Zipperman said. “Our school police is concerned and focused on young people.”

The latest photo of the entire LA Unified police force.

A big force

In the entrance of the school police department at 125 N. Beaudry Ave. there are glass cases containing badges, hats and pictures of old police cars once used by the department. There are also waist-high trophies from various tournaments the police department won with student teams, as well as plaques of honor from around the country. On top of the glass counters are brochures of their youth programs in English and Spanish.

Established in 1948, the Los Angeles School Police Department is the largest independent school police force in the country — perhaps the world — with 410 sworn officers, 101 school safety officers and 34 civilian support staff that work 24/7 to patrol schools that are spread out over 710 square miles and 26 cities, many of which have their own police departments that are much smaller.

In fact, the police force for the nation’s second-largest school district is the fifth-largest police force in Los Angeles County and the 14th largest in California. By comparison, the largest school district in the country, New York, has 200 sworn police officers.

There’s a canine unit, a bike team, an Honor Guard, an investigations unit, a Critical Response Team, an Anger Management Program and Police Academy Magnet Schools. They have their own police cars and motorcycles in seven divisions and have Multi-Assault Counter-Terrorism Attack Capabilities (MACTAC) for terrorist threats.

The LA school police regularly interact with more than 13 city and county law enforcement agencies as well as state and federal police entities and emergency services. Learning how to better communicate with other policing agencies became a major topic of conversation this summer.

Sgt. James Ream, center, on the first day of school at Haddon Avenue STEAM Academy.

“Over the summer we had sessions where we visited early education centers and held regular site visits with elementary schools and Beyond the Bell programs to interact with kids,” Zipperman said. “We wanted them to see us positively and show our faces more often.”

On the first day of school this year, Chief Zipperman attended press conferences with Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, members of the school board and Superintendent Michelle King at John C. Fremont High School and later at the new all-girls school Girls Academic Leadership Academy. Meanwhile, his officers made their presence known throughout the district from Day One.

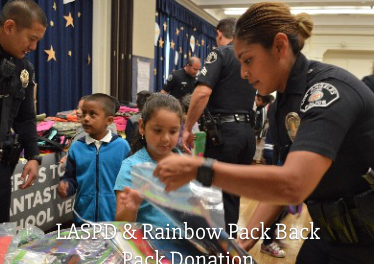

In the northeast San Fernando Valley in Pacoima, Sgt. James Ream kicked off a backpack giveaway and told the Haddon Avenue STEAM Academy elementary students, “Those of us in uniform who you may see at the school have come to protect you. If you see a police officer, we’re your friends.”

Ream is also in charge of scheduling officers to visit elementary schools around Halloween to read spooky stories and encourage people to donate books to the school. “We get the kids to see us as people who want to help,” Ream said.

During the holidays the police department is involved in shoe drives, book drives and helping other nonprofits deliver food to school families or holiday gifts to needy children. They visit the USC Children’s Hospital, hold a Teddy Bear Drive and sponsor leadership activities for youth throughout the year.

“We do a lot of things on a daily basis that people don’t know anything about, and a lot of that is done on the officers’ off time,” Zipperman said. “We try to provide a sense of security to the students so that they know they will come to a safe campus. That leads to a better learning environment, and better attendance and better outcomes for students.”

He added, “The officers are out there connecting with kids in ways other than when we have to take enforcement action.”

But are schools safer?

But are schools safer?

It seems like an easy question, but for Chief Zipperman there’s no easy answer. Are schools safer than when he took over the police department five years ago? Are teachers less likely to be assaulted?

“The answers are not that easy, it depends on what prism we’re looking through at how to gauge a safe school,” Zipperman said. “Is it a lack of crime? Is it by how many weapons are confiscated? Is it by surveys asking how safe we feel coming to school? Or is it gauged by the amount or lack of suspensions or expulsions?”

The reality is that expulsions and suspensions have gone down, but fighting and physical aggression, according to the district statistics, have increased from 2,425 incidents in the 2013-14 school year to 3,103 in the 2014-15 school year. Last year’s iSTAR summary (Incident System Tracking Accountability Report) is not yet available.

But in the latest statistics, there were 1,163 reports of sex crimes or inappropriate sexual behavior, 746 incidents of finding illegal or controlled substances and 839 weapons confiscated.

• Read more: Here is LAUSD’s Emergency/Disaster Plan.

“I don’t know if you could correlate that with more weapons being recovered. There are weapons being brought to campus probably every day,” Zipperman said. They’re not always firearms but could include knives or sharp objects or something that could cause harm to a student or teacher. “Is the fact that we are finding those objects making the campus safer?”

The school police also patrol neighborhoods around schools where bullying or thefts could occur by gangs threatening schoolchildren. They offer a Safe Passages program, marking walkways for students that are patrolled by safety officers in potentially dangerous neighborhoods.

During the summer the police trained for dealing with an active shooter on campus and for lockdowns and incidents involving narcotics.

After looking at crime statistics at each school, the school police assess what areas need more resources or anger management courses or more patrols. They collaborate with the educators at the school to better understand the climate of the school, Zipperman said. And they coordinate with local police departments.

“What I can say is that over the last five years, there has been more involvement with school police in preparing our schools to respond to issues that could be an act of violence against the school,” Zipperman said. “Our schools are better prepared when it comes to emergencies than ever before.”

Zipperman with Mayor Garcetti on the day the schools were shut down.

An emergency test run

On Dec. 15 last year, just before winter break and just after 14 people died in the San Bernardino terrorist attack, every LA Unified school was ordered closed because of an email threat. The Internet hoax caused enough concern that every campus was shut down and searched for weapons and bombs.

At a press conference broadcast nationwide, Zipperman stood at the podium with the county sheriff, Los Angeles police chief and the mayor to explain how they were coordinating resources and checking every school.

“December 15th was a test on how we can respond to an emergency and get the word out quickly when it involves something of that magnitude,” said Zipperman, who is finalizing a report to the superintendent about the incident and their reaction times. “There are things we learned that we can improve upon, but it showed how quickly we were able to get the word out to the parents and our city, county and state partners about what is happening. We have room for improvement. A lot of it has to do with communications. We can respond next time in a more efficient and effective manner.”

Zipperman keeps tabs on national dialogue and trends in keeping schools safer. Some of them he disagrees with — and isn’t afraid to say so.

“I am not a proponent for teachers carrying weapons, no,” Zipperman laughed. “I have heard all of the crazy proposals nationwide and no, I’m not a proponent for that.”

If a student assaults a teacher, there will most likely be an arrest, the chief said. “We will look at the age and circumstance, but if a student purposely assaults a teacher, that student will get arrested,” he said.

“There is a sense of having us in and around these schools that is priceless, and these kids need to see that safety and protection on a daily basis,” Zipperman said. “And so do the teachers.”

The trophy case at the entrance of the school police office.

Fighting rumors

The anti-immigration rhetoric during the presidential race and incidents last year in other parts of the country with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) caused a sudden drop in attendance at LA Unified and unprecedented fear among students and their families.

“There was some rumor that there was a perceived pending enforcement of ICE with schools, and I think the rumor took on a life of its own,” Zipperman said. “Neither I nor my colleagues were made aware of any ICE enforcement going on at schools. I could see the angst it would cause particularly at LAUSD because we have such a significant population that could be affected. We are inclusive, we don’t care what anyone’s status is, and our goal is for the district to provide a safe and nurturing learning environment, and it is our job as police to do that.”

The school board doubled-down on that by passing a resolution emphasizing that they don’t want federal agencies coming to the schools without the school police involved, and they offered support to children and families concerned about deportation fears.

What about charters?

Although the school police duties don’t specifically include monitoring independent charter schools, they will not turn their back on charters that may need help, Zipperman said.

Four independent charter high schools are located on district school property and many are co-located on district school sites, so those are covered by the school police. Independent charter schools under the LA Unified umbrella that are on private property usually are handled by the local police department in that area.

“These are all our students, so if they need help, of course we will respond and figure out who deals with it later,” Zipperman said. “We have responded to calls from independent charter schools not on district property and we will send a car if it’s an imminent safety issue. They are absolutely part of our schools.”

Some of the charter schools do not like some of the district policies such as required daily random wanding of their middle school and high school students. Charter schools signed a letter saying they will not do it. It’s not a request that came from the police department but from the school board, and the police don’t get involved in conducting the wanding searches unless something illegal is found.

Superintendents and school board members have regularly heaped praise on Zipperman and the school police for work they do. Three officers were recently honored with Medals of Valor at a school board meeting for saving a woman who was going to jump off a bridge not far from a school in East Los Angeles.

“I have every confidence that our school police continues to keep our children and school population as safe at school than they are during most of the rest of their day,” said school board President Steve Zimmer. “And we will not compromise on safety for our children.”

The school police budget is about $60 million, and the department is continuing to recruit and hire officers. The average school police officer makes about $87,000 a year, compared to the average teacher making about $70,000 a year. The average sheriff’s deputy makes $52,000, and the average LAPD officer makes about $110,000. Zipperman is among the highest paid administrators at LA Unified, making $170,475.

The school police budget is about $60 million, and the department is continuing to recruit and hire officers. The average school police officer makes about $87,000 a year, compared to the average teacher making about $70,000 a year. The average sheriff’s deputy makes $52,000, and the average LAPD officer makes about $110,000. Zipperman is among the highest paid administrators at LA Unified, making $170,475.

Restoring justice

Zipperman came to save the school police from a checkered history. One police officer was convicted of sexual harassment of a student, which led to one chief retiring early, and then an investigation by LA Weekly in 2007 led to previous police Chief Lawrence Manion announcing his resignation.

Zipperman came from 32 years at the LAPD where he worked in vice, patrol, narcotics and the Special Response unit. He graduated from Taft High in the San Fernando Valley and holds a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice with a minor in sociology from Cal State Bakersfield and a master’s degree in organizational leadership from Woodbury University.

Zipperman said he is acutely aware of the budgetary constraints that the school board faces and doesn’t have any wish list other than for more people to patrol the schools. He does well with what he has, he said. Cutting the budget of the school police is not something the school board said they want to do.

However, Zimmer was glad to see that automatic weapons and a military-grade mini-tank were given up by Zipperman after student activist groups protested over the federal sharing of military surplus equipment. The police chief explained that the weapons were never intended for use on campus, but merely being used for training purposes. The groups called for an apology and a decrease in force for the police department as well as an accounting for all the weapons. After a few demonstrations and a disruption of a meeting, Zipperman sent out a letter to the group, met with the students and quelled their concerns.

“It is important to figure out how to best facilitate free speech among the students and have conversations when there are demonstrations nationally such as with Black Lives Matter,” Zipperman said. “We know students want to participate in the political part of it.”

Zipperman has seen some progress with the district embracing restorative justice programs, but he remains skeptical about its ability to deter all criminal activities on campus. The program allows students to address their problems and “acting out” among peers in a setting that does not criminalize their actions and keeps them out of court.

“We don’t want some to think that this is just an easy way to stay out of the criminal justice system, and of course we don’t want our students to end up getting arrested,” Zipperman said. “We have to have them learn from their mistakes and mentor and guide them.”

He added, “Restorative justice can’t just be a way out of accountability, or an excuse for avoiding another more appropriate avenue (of justice) for someone who has no intention of changing their behavior.”

Inevitably, the news headlines of the day seem to strike against the police chief’s ideal of trust with schoolchildren, but he keeps working on it in LA.

“Our goal is to always have that relationship with young people, all the children, and their families,” Zipperman said. “We are always looking for ways to build and foster those relationships.”

He added, “These days it becomes even more of a necessity to build those relationships at the school setting so that those attitudes continue when they’re no longer at school.”

- (Credit: LASPD)

- Cadets at Reseda High’s Police Academy Magnet. (Credit: LAUSD)

- Mayor Eric Garcetti, Dr. George J. McKenna III, James J. Cole Jr. and Steve Zimmer.

- Chief Zipperman of LA School Police meets with students in the college center at John H. Francis Polytechnic High School to discuss their future plans.

- LASPD Deputy Chief Fontenette at Girls Academic Leadership Academy with Deputy Secretary of Education James Cole, Jr.

- El Jefe Zipperman luce un sombrero de Dr. Seuss para apoyar