In Every Language, Oakland Schools Makes Enrollment Possible for Newcomers

Jo Napolitano | December 18, 2024

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

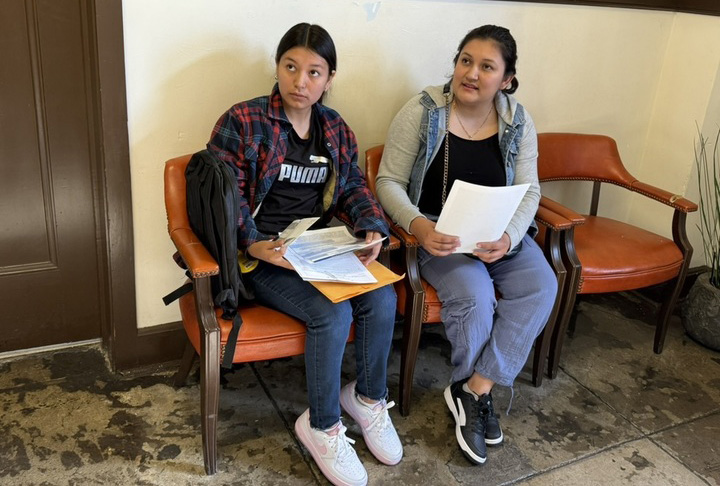

Nate Dunstan, program manager for refugees and newcomers at Oakland Unified School District, registers 17-year-old Marvin Rivas Zavala, recently arrived from El Salvador. Zavala is accompanied by his mother (center) and his cousin (left). (Jo Napolitano)

Whether a prospective student speaks Spanish, Vietnamese, Cantonese, Mandarin, Arabic or Mam — a Mayan language used in parts of Guatemala and Mexico — Oakland Unified School District’s enrollment office has a staffer who can help.

If a newcomer communicates using a less common tongue like Dari and Pashto — spoken in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran — they’ll call in favors from local community groups to translate.

What staffers won’t do, unlike in many other districts across the country, is allow a language divide to become a barrier to an immigrant student’s enrollment.

“We take seriously our call to be a sanctuary district and a community school, not just in name, not just as a tagline or the sexy new initiative, but as an authentic calling,” said Kilian Betlach, the district’s executive director for enrollment.

The approach stands out compared to schools throughout the U.S.: A recent 74 investigation found older newcomers were rampantly denied admission, including hundreds of times in states where they have a legal right to attend based on their age.

Our reporting showed schools allow a wide variety of staff to answer critical enrollment questions — often incorrectly — and are prone to steer these students to adult education, night school and GED programs. Many deny admission based on a lack of transcripts or other paperwork, obstacles Oakland tries hard to overcome.

When enrollment requests to the 34,000-student Bay Area district are simple, involving students 17 or under who have at least some of the necessary paperwork, registration at the district begins and ends with enrollment office staff.

But when a newcomer has no proof of address or birth certificate and is over age 18 — they’re sent down the hall to the Refugee and Asylee office, which handles the most challenging cases.

“We hope to be the front door to services in Oakland,” said Nate Dunstan, program manager for refugees and newcomers at the district.

For many families, he said, his office is their first point of contact with any local governmental entity.

“We want to help make it a smooth entry to our schools, make sure kids are placed in the right program … that is easy to get to and has supportive services,” he said.

Marvin Rivas Zavala, who came to Oakland’s enrollment office on a recent sunny morning alongside his mother and cousin, was in the equivalent of 11th grade in El Salvador when he left for America.

He arrived in the United States in late October speaking little English. The district would have placed the 17-year-old in a higher grade if he was proficient in the language, but Dunstan instead enrolled him in 10th to give the teen more time in high school.

While some new students are upset to see graduation pushed back, Rivas Zavala is focused on long-term goals: He wants to be fully prepared for college, he said, like the other young people in his family — including his brother and cousin — who have already enrolled in higher education in the U.S. and abroad.

“I want to do software engineering after high school,” he said with certainty.

It took his family less than 30 minutes to register him. Staffers say they’re determined to make the process quick and easy.

In their initial intake but after a child is enrolled, they ask about immigration status in the event that they can help — by providing, for example, the name of a legitimate immigration attorney — and make sense of foreign transcripts.

If they have a relative in a particular high school, staffers might first send a new arrival there hoping it will encourage their attendance before they switch to a more appropriate setting. Oakland Unified might also place them on a campus where they can find peers from their homeland to ease their transition.

Esmeralda Flores Paredes, 17 and from El Salvador, came to the United States on Sept. 8 and was in government detention in Texas for nearly a month before she was released to her sister in California on Oct. 4.

She finished high school in El Salvador — even completing a few months of college there — and hopes to graduate high school here in a year.

After that: “I want to keep studying,” said the young woman, who plans on working in the tourism industry.

After a quick chat with enrollment staff, Flores Paredes was assigned to Castlemont High School and then transferred to another campus, Rudsdale Continuation High School, which has a program designed to make attendance and graduation attainable for older newcomers.

Enrollment staff use students’ first visit to help them — and their families — apply for public health insurance and ask if they are facing a housing crisis or any other issue that could keep them from attending.

“That’s our ultimate goal, that the student is in school,” Dunstan said. “But there are, of course, a million reasons why it would be hard for that to happen.”

Dunstan and his colleagues gave their cell phone numbers to several newcomers who came through the enrollment office earlier this year, telling them they were not only concerned about their registration, but their well-being.

Seeking school admission can be anxiety provoking for non English-speaking families, who have no idea whether staff will accommodate them. Their enrollment requests come at a particularly perilous time: On the eve of President-elect Donald Trump’s second term of office, a fight he won after vilifying immigrants.

These students and families don’t know whether he will follow through on his pledge to rid the country of its roughly 11.7 million undocumented residents: While the promise seemed critical to his victory, it’s been criticized for its cost and impracticality.

Cristhian Pineda Diaz, an unaccompanied immigrant youth specialist, enrolls newcomer Jose Rafael Villegas Pena, 18, as his brother looks on. (Jo Napolitano)

Cristhian Pineda Diaz, an unaccompanied immigrant youth specialist, enrolls newcomer Jose Rafael Villegas Pena, 18, as his brother looks on. (Jo Napolitano)“I mean, it’s difficult to see families overwhelmed about the election outcomes,” said Cristhian Pineda Diaz, an unaccompanied immigrant youth specialist. “It’s also difficult to hear students being afraid to be separated from their parents. But I’m hopeful because we will do our best job to help families in every way possible.”

New students leave with basic supplies, including backpacks, pens, pencils, binders, folders and notebooks — whatever local charities and other organizations provide — and when they come with younger siblings, they might also leave with diapers or new shoes.

If they need immunizations and find the most popular clinic is backed up for months, enrollment staff will find other sites that can help. And if a family is overburdened by bills, the district can connect them with community-based organizations that can offer financial assistance.

In an effort to further ease the registration process, newcomers’ receiving schools are quickly notified about their enrollment, with students’ academic and immunization status almost immediately available through a shared database.

Staff will also travel from the main enrollment office to another location in this 78-square-mile city that might be easier for newcomer families to reach.

That’s just the effort Oakland Unified makes for those students who actively pursue registration: It has an entirely different plan for those who don’t.

Staffers also look for would-be students in the community. Qoc’avib Revolorio, another unaccompanied immigrant youth specialist, has, in the past, teamed up with Street Level Health Project, a local nonprofit that delivers food to day laborers at area pickup spots.

“Since that organization has a bit of street cred, I would join them on their rounds from 7:30 to 10 a.m.,” said Revolorio, who would make these trips prior to the start of each semester or just before the school marking periods would begin. “We would hand out flyers, shake hands, ask any of the laborers if they had children or nieces or nephews that just arrived … that we could help personally enroll in school.”

He’d use the opportunity, he said, to scope the crowd for younger faces, approach potential students with a smile, talk to them about learning English and about the district’s soccer program before he’d ask if they needed any help with immigration issues.

Staff also regularly call former dropouts and ask why they are no longer attending and conduct home visits when necessary. Much of Dunstan’s work is funded by the California Department of Social Services. A host of other organizations offer further assistance to newcomers and their families: Oakland Public Education Fund, for example, provides families with money after they attend a financial literacy class while New Anchor Foundation contributes up to $2,000 toward rent.

The district erects billboards to encourage families to enroll by visiting ChooseOUSD.org, runs targeted digital and Spanish radio ads that promote pre-K and transitional kindergarten, a bridge to elementary education that has been particularly beneficial for English learners. They even operate a booth at the local Día de los Muertos celebration, sharing similar information.

Oakland aims to reach families wherever they are and, to that end, technology is key, Betlach said. Its previous enrollment system wasn’t optimized for mobile, making it difficult for many newcomer families to register.

“It looked like Netscape navigator,” he said, referring to the long-defunct web browser. “Low-income communities use all of their internet through the phone, so if your tools are not mobile enhanced, you are pushing out low-income users.”

Sometimes, enrollment staff said, it can take months, or even a year to convince students to pursue their education. In such cases, staffers might help them obtain work permits, find jobs, locate safer housing or child care so a teen is freed up to learn.

They try hard to make as few refusals as possible, recently admitting, for example, a 20-year-old from Guatemala with no high school credits. They fought for nine months to help her find a path to attendance.

The district welcomes her — and scores of others just like her — during a particularly difficult time, as it faces a projected $75 to $95 million budget deficit next year and is wrestling with closing and consolidating schools.

“There is a moral force to recognize and welcome all members of your community, not just those that fit into neat boxes or will help drive data-driven achievement narratives,” Betlach said. “We believe this, truly, even when no one is looking.”

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.