L.A. pods: In parks, backyards and old storefronts, small groups offer children some of what they’ve lost in months of online instruction

Linda Jacobson | January 5, 2021

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Kindergartner Malcolm Watts-Cover gets help with math at a pod in south Los Angeles. (Linda Jacobson)

Los Angeles

Pam Marton and Sharon Fabian — longtime educators in the Los Angeles schools and friends since kindergarten — were set to celebrate their retirement this year with a trip to Croatia when the pandemic cancelled their plans.

It wasn’t long, however, before they “started getting emails and calls from … families, parents who were really freaking out,” Fabian said. “Pam turned to me and said, ‘We know a lot of fabulous instructors. We have reputations. Why don’t we start a company?’”

Now they bring together experienced teachers, teaching assistants and children needing support with remote learning — small groups otherwise known as learning pods.

Initially viewed as a short-term solution to COVID-19 school closures, pods have become a necessary support system for many families as districts push reopenings back to 2021 or return to distance learning after several weeks in the classroom. Whether informally organized by parents, arranged by for-profit tutoring and child care companies, or matched through social media, supporters say pods are likely to outlast the pandemic.

Darleen Opfer, a researcher at the RAND Corp., said there’s a common theme running through the many versions of pods, whether they meet in a school, a park, or someone’s home.

“A lot of parents are afraid their children are falling behind,” she said.

Those fears are not misplaced. A new analysis by McKinsey & Company confirms earlier predictions of learning loss, particularly in math and among students of color. Recent data from nonprofit assessment organization NWEA shows similar patterns.

From Los Angeles to New York, pod demographics run the gamut, from well-off families employing professional educators to replace districts’ remote instruction to families getting scholarships for a few extra hours of tutoring a week.

Marton and Fabian call their new enterprise Blue Ribbon Educators, after the U.S. Department of Education’s prestigious school recognition program. As principals in Los Angeles Unified schools, they often engaged in some “healthy competition” for the honor and led the only two schools in the district to receive the designation in 2019.

Working only with families whose children are still enrolled in school, they’ve matched educators with at least 10 home-based pods, primarily on the westside of Los Angeles. And they provide ongoing support to both the teachers and the families around group expectations and COVID-19 safety protocols. If conflicts arise, they offer advice, but Marton said, “We don’t want to be too principaly.”

Former principals and “travel buddies” Pam Marton, left, and Sharon Fabian on a trip to Paris. (Pam Marton)

‘Connecting with the kids’

One advantage enjoyed by southern California pods is they can meet outside during the winter months. That’s exactly what eighth-grade teacher Abbey Edwards and her friend Monica Kinnan, an exercise physiologist, had in mind when they founded Iron Kidz.

Meeting in a park in Murrieta, a fast-growing residential community about 80 miles east of Los Angeles in what’s known as the Inland Empire, the program emphasizes physical exercise and hands-on activities.

On a windy afternoon, Edwards gives students a lesson on maps by sketching the playground, picnic tables and parking lot in chalk on the basketball court.

“Everyone say, ‘aerial view,’” Edwards tells them. “This is what the park looks like if you’re a bird.”

Pod teacher Abbey Edwards gives the group instructions before a science activity. (Linda Jacobson)

Instead of tutoring or monitoring virtual class sessions in someone’s dining room, Edwards and Kinnan designed their program to get children away from screens for a few hours. On this Monday afternoon, two eighth grade boys earned community service credit by preparing activities for the children, and Kinnan’s college daughter Tyler gave the children lessons in American Sign Language.

With schools closed, the program provides the children a chance to make friends and helps burn off energy they might have expended on recess or sports, said Emily Silver, whose 6-year-old son Mickey is in the program. “I love the balance they have with the education and the running around,” she said. “It’s a great blend of interests for such a wide age range.”

To get started, Edwards and Kinnan registered with Wonderschool, a company in 17 states and the District of Columbia that helps at-home child care providers find clients and operate their businesses. Now the two are contemplating a second site in San Diego, and Edwards, who still teaches in a school that was virtual before the pandemic, has even toyed with making the pod business her full-time job.

“To do this would be my ultimate goal,” she said. “I love connecting with the kids.”

Six-year-old Mickey Silver, left, and 8-year-old Travis Kowalkoski have become friends at Iron Kidz. (Linda Jacobson)

‘You have to be there to inspire’

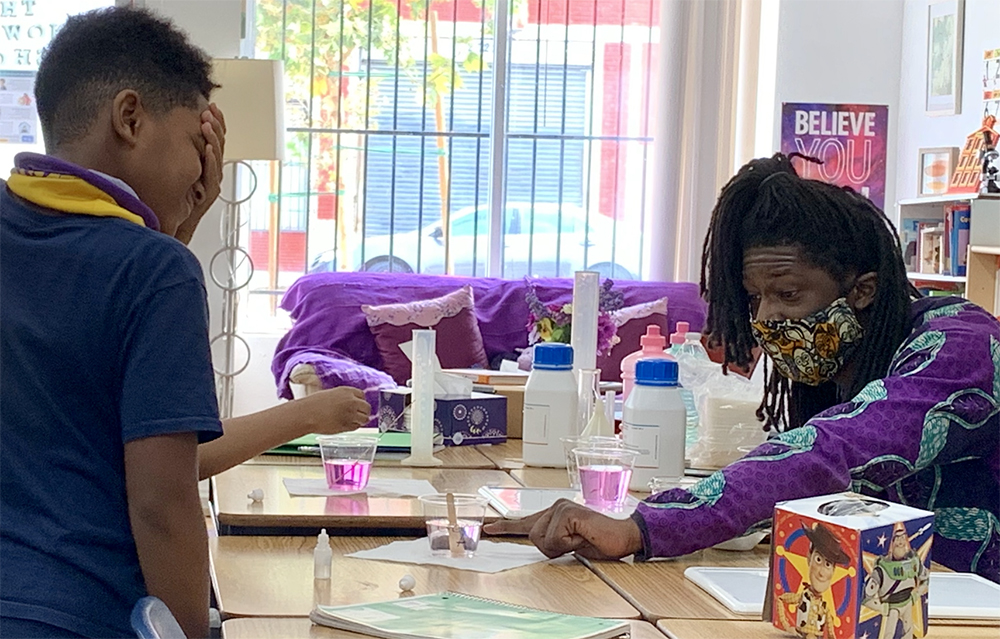

Another diverse mix of children — from public, charter, private and homeschools — assemble each day in a nondescript storefront in Los Angeles’s Crenshaw District, where 8-year-old Sofia Peterson is sliding color-coded popsicle sticks across a table. She replaces 10 skinny ones with a wider stick, mumbling calculations as she adds 214 and 396.

“So far, so good. Now do it on paper,” instructs Michael Batie, a Black man with a graying beard, sporting a t-shirt and camo shorts, as he looks over her shoulder.

Meanwhile, kindergartner Malcolm Watts-Cover uses an abacus to complete a long list of equations that add up to 10. Batie’s shelves are stocked with bins of geometric shapes, flashcards, cubes and other math materials.

“I don’t think you can teach math on Zoom. You have to be there to inspire, encourage, cajole,” said Batie, a STEM educator who once built weather and communication satellites for Raytheon and other aerospace companies. When the spring lockdown forced his afterschool program, STEM54, to close, he reinvented himself as a pod teacher, working with a consistent group of elementary and middle school students throughout the week.

Malcolm attends the pod with his older siblings, Jaden, a fourth grader, and Le’ona, a first grader. All three attend a Los Angeles magnet school. They participate in three to four hours of live instruction and off-line assignments at home before their father drops them off at the pod around 2 p.m., where they get three to four hours of extra tutoring and homework time.

“We had stuff going on that prevented us from spending time on schoolwork,” said Fernando Cover, their father. “Parents can only do so much.”

Bradley Peterson, Sofia’s dad, was preparing to travel to Spain, where he’s starting a business, when schools closed in March. Initially, his daughter had about an hour each day of live, online instruction.

“I saw my daughter sitting there, playing with an iPad all day,” he said. “I thought, ‘How am I supposed to work and educate at the same time?’”

Math educator Michael Batie works with Sofia Peterson on a math calculation. (Linda Jacobson)

A new pod database

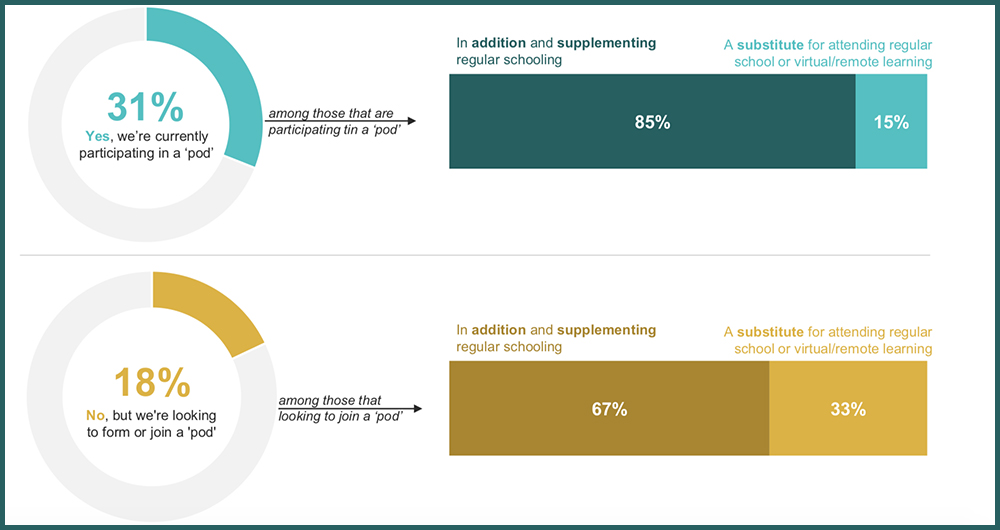

Nationally, the pod model has assumed many forms since the summer, when parents began pooling funds to hire teachers and share responsibilities for child care and the oversight of remote lessons. Some families went all in, withdrawing from their schools to form groups of homeschoolers. But one recent survey, from EdChoice and Morning Consult, showed that the majority of families chose pods not to replace their school’s remote learning but supplement it.

Around the country, nonprofit providers and school districts ramped up pods to make in-person support available to families who lack resources to hire their own teachers.

A technology pod in the Glendale Unified School District (Glendale Unified School District)

Now researchers hope to capture the scope of the pod phenomenon, including a catalog of the organizations running them and the ways in which families are using them, as they track the long-term impact of this disruption on students’ learning. The Center for Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington will scan the nation to create a pod database that identifies different approaches as well as some of the lessons and the political challenges experienced along the way.

For pods offered by organizations other than school districts and nonprofits, costs typically depend on how many days children attend, the number in the group, and the credentials of the teacher. A paraprofessional, for example, costs less than a teacher with a master’s degree. The Crenshaw pod costs $25 an hour, but some parents pay less if their children qualify for free or reduced-price meals, and others involved might cook lunch to trade for the service. Iron Kidz charges up to $240 a month, but Edwards and Kinnan offer some scholarships for lower-income families. Data from EdChoice shows that parents are willing to pay an average of about $140 per month to participate in a pod.

Of the 31 percent of families participating in pods, a large majority responded that they are using the groups as a supplement to their school’s distance learning program. (EdChoice and Morning Consult)

The support is ‘worth it’

Beyond costs and logistics, the bigger question, said Opfer with RAND, is whether children perform better academically in a pod arrangement — and if so, why.

“I can imagine that if some parents feel their children learn better in a pod than they did at school, then they will continue them even when schools reopen fully,” she said.

That’s what Mary Lee, a grandmother in Los Angeles, has in mind, now that the pod in Crenshaw has solved many of the dilemmas that remote learning created last spring. Back then, she had to share her laptop with her grandson Caden, a fourth grader, because his charter school only issued them to older students.

On a recent Wednesday afternoon at the pod, Le’ona Watts-Cover was getting some one-on-one help with a school-issued iPad, and Caden was doing a first draft of an essay.

Pointing to his pocket, Caden said his first priority when he arrives at the pod is to put away his phone and connect to Zoom.

“My grandma, she really wants me to succeed in school,” he said “That’s why she sends me here.”

An administrator in the Los Angeles schools for 35 years, Lee now works as a consultant who coaches parents of young children how to navigate the district. As a career educator, however, she’s frustrated by the strict structure of Caden’s virtual school day.

Caden Lee, left, learns about acids and bases from Brandon Sankara, a science educator who visits the pod in Los Angeles’s Crenshaw District a few times a week. (Linda Jacobson)

“They’re not getting real breaks. If he leaves to go to the bathroom, the teacher says, ‘Where are you? You’re not on screen. Get back on screen,’” Lee said. “They need to be a little more child-friendly during this time.”

She described the pod as nurturing, but said Caden’s work habits are improving as well. He’s more organized, and he’s turning his schoolwork in on time, she said. Even if his school reopens, Lee thinks Caden will stay in the pod.

Besides, he’s more open to taking direction from the pod teachers than his grandmother, she said. “It’s worth it to have the additional support.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.