LAUSD Taps Private Funders to ‘Level the Playing Field’ Between District Schools

Sara Randazzo | January 6, 2026

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Concerned about longstanding disparities between Los Angeles schools and a possible loss of state and federal funds, the Los Angeles Unified School District is tapping private philanthropy to fill the gaps.

The district recently reignited its dormant nonprofit, the LAUSD Education Foundation, hiring a new executive director to court dollars from corporations and foundations. The effort has brought in some $26 million so far, including from well-known players in L.A. entertainment and business, on its way to a $100 million goal for the foundation’s first five years.

A renewed focus on raising private money for school districts across the country comes as student needs are growing and leaders worry about shifting federal policy, education philanthropy officials said.

“What’s occurring right now is that those that don’t have them are forming foundations, or reforming them if they’ve gone dormant,” said Mike Taylor, head of the National Association of Education Foundations, who said he’s been fielding calls since the summer from school districts looking to navigate the uncertainty around federal funding and leverage community resources.

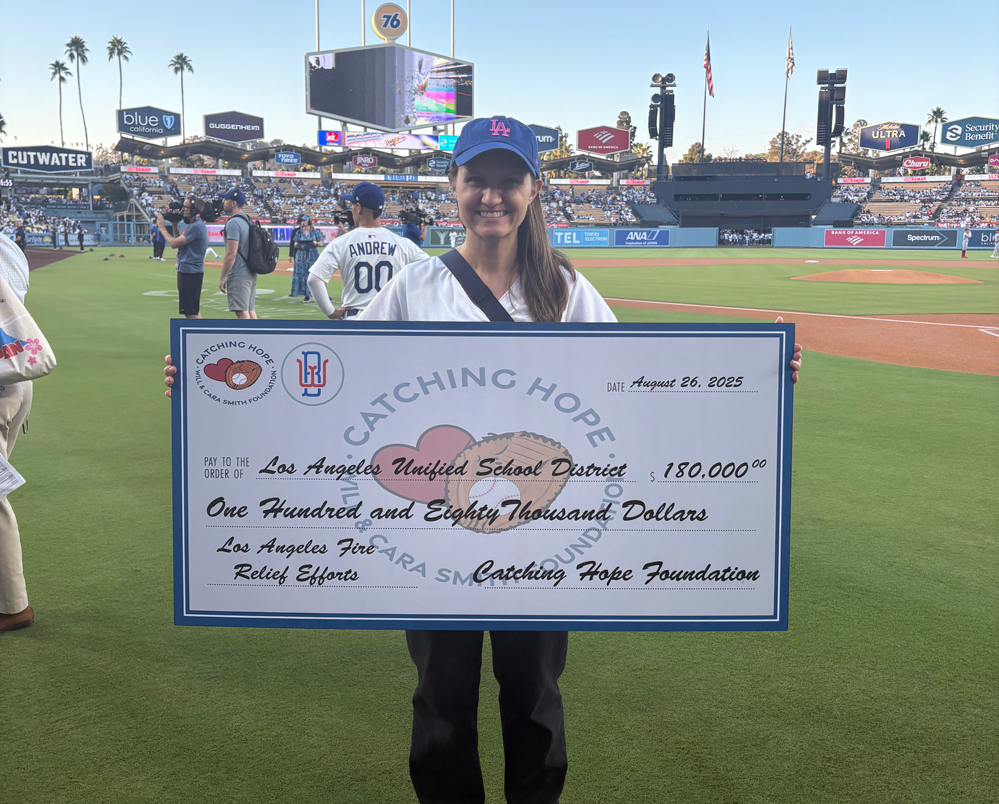

In Los Angeles, the initial fundraising push has helped families impacted by last year’s wildfires and supported the district’s neediest schools.

“I want to level the playing field,” said Sadie Stockdale Jefferson, who came in to lead the LAUSD foundation this summer after serving in a similar role for Chicago Public Schools and running a University of Chicago think tank focused on public education. “We’re taking the best of what we know works to improve education and ensuring those initiatives reach the schools and classrooms that need them the most.”

A major initial focus of the foundation will be on what LAUSD Superintendent Alberto Carvalho calls “priority schools,” a group of 121 campuses with lagging academic performance and the highest student needs in a district that educates everyone from the wealthy elite to families experiencing homelessness or poverty.

Jefferson recently saw a breakdown of private support to district schools by region and said she realized: “The disparity is shocking,” adding she wants foundation money to primarily support campuses without their own parent-run fundraising efforts.

The philanthropic money is still a drop in the bucket in the district’s more than $18.8 billion annual budget. But it represents a potential new revenue stream at a time when LAUSD continues to shed students and run a deficit.

Carvalho is looking to the foundation to support students in ways the district can’t, like sending homeless students off to college with a new laptop, or providing emergency cash to families impacted by the wildfires. “Sometimes the need is acute,” Carvalho said, with foundation money typically being deployed quickly and with less bureaucracy.

Many of the needs Carvalho ticked off as foundation priorities are those students face outside the classroom. But he said he’s also open to private money supporting the district academically, particularly in the priority schools. District support for priority schools involves teacher coaching, strengthening curriculum and providing tutoring.

“Government dollars will only go so far, and there are unmet needs that often foundations can address and support,” Carvalho said.

The foundation has also taken on music education, riding off the popularity of “The Last Repair Shop,” an Oscar-winning short film about the highly skilled team that keeps scores of district-owned instruments working for LAUSD students. Jefferson said she’s hoping to replicate a sponsor-a-school program she ran in Chicago, offering businesses a way to directly help local schools.

Using private money for public education can be controversial, particularly when funders are seen as exerting too much pressure or pushing for school reforms like charter schools.

Carvalho and others involved in Los Angeles’s fundraising say they’re aiming to avoid that tension as they address critical needs in the district of 400,000 students.

Of the nation’s 13,000 school districts, around 6,000 have foundations, the majority volunteer-run, Taylor said. The focus of district foundations has evolved, he said, from being thought of as a vehicle to buy extra books or classroom materials. The needs and challenges have deepened since the pandemic. Philanthropic money now goes toward building partnerships for workforce development, supporting teacher retention and addressing student mental-health challenges, Taylor said.

LAUSD’s foundation has recruited board members from local business, education and philanthropic organizations.

Board Chairman Michael Fleming, the president of the David Bohnett Foundation, said he was drawn to the role after hearing Carvalho’s vision for an organization that could move fast and target specific goals, including investing in the priority schools.

He’s also committed to bridging the divide between public and private funding. “There is this innate distrust sometimes between a government entity and philanthropy, and vice versa,” Fleming said. “They each see the world very differently and say: ‘You don’t understand the way we operate.’ I think that’s false.”

Enthusiasm for private investment in public school districts has fallen in and out of favor over the decades. Initial waves of corporate and foundation money aimed to revolutionize education.

“When things don’t dramatically get better, the energy and resources and attention ebb,” said Jeffrey Henig, a professor emeritus at Columbia’s Teachers College who has followed education philanthropy. Many private foundations doubled down on charter schools, which then made school districts wary of partnerships. In Los Angeles, a nonprofit launched by LAUSD leaders in the 2010s later merged with an entity that backed charters, putting it at odds with the district it initially set out to help.

Henig sees today’s philanthropists more focused on supporting strong school leaders, rather than looking to fundamentally disrupt the way education is delivered.

That shift makes sense to Erica Lim, a senior program officer at the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation. Broad, along with the foundations of “Two and a Half Men” co-creator Chuck Lorre and L.A. Clippers owner Steve Ballmer, recently gave $11 million to the LAUSD foundation to support its priority schools.

Lim said she was encouraged by the stability Carvalho has brought to LAUSD since he joined in 2022 after a string of short-tenured leaders. The former Miami-Dade Public Schools superintendent now has a contract to keep him in the L.A. job until at least 2030.

“We’re not looking to backfill or solve really systemic budget issues,” Lim said. “That’s for district leaders to solve.” Instead, Broad wants its investments to help kick-start new initiatives or scale programs that show promise.

Carvalho said the district won’t be turning to philanthropy to fund core areas of the budget. That said, he could see the foundation being used as a stopgap if, for instance, the federal government cut off longstanding funding to support English language learners. “That would be a legitimate support from the foundation,” Carvalho said, “Which could be a likely scenario in the months to come.”

In reviving the foundation, Carvalho changed the bylaws to give himself less power over its board, a move he saw as helping ensure its independence. Jefferson works with the LAUSD Education Foundation board to direct funds, with district input.

Fleming, the board chair, said he’s looking for the foundation to outlast the many prior attempts and avoid drama. “We simply want to get resources for the schools and for students,” he said. “That’s it.”