‘Long road to recovery’: Math, reading scores remain below pre-pandemic levels

Linda Jacobson | July 26, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

The nation’s students showed small signs of academic recovery during the 2021-22 school year, but high absenteeism, quarantines and short-term closures “thwarted hopes of a strong comeback,” new data shows.

Overall, the findings — from 8.3 million students in 25,000 schools — “point to a long road to recovery still ahead,” wrote researchers from nonprofit testing provider NWEA.

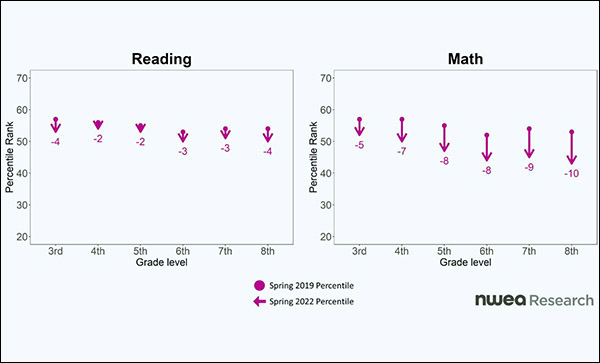

The arrows show how this year’s MAP scores in reading and math compare to 2019. (NWEA)

With the fourth pandemic school year approaching, the report underscores the need for urgent action to address learning loss, the authors wrote. MAP test data shows that it could still take three to five years — in the middle grades, more than five — to return to pre-pandemic performance.

“It was a big question mark,” Karyn Lewis, director of NWEA’s Center for School and Student Progress, said about what to expect this year. “We were really hopeful at the beginning, but it was much more difficult than we thought it would be.”

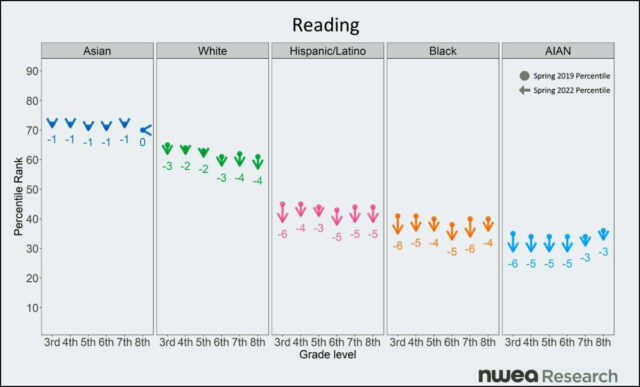

Compared to a pre-COVID sample of students who took the assessments, reading scores are 2 to 4 percentile points lower and math scores remain 5 to 10 points lower. High-poverty schools, as well as Black, Hispanic, and indigenous students, are having a harder time bouncing back, the data shows. And, as other assessment experts have noted, reaching pre-COVID levels in math and reading does nothing to address long-standing achievement gaps.

There is a larger gap between 2019 and 2022 performance for Black, Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska native students than for Asian and white students. (NWEA)

‘Leaning in to those grades’

But NWEA’s findings also point to some hopeful patterns that weren’t present a year ago. The pace of recovery between fall and spring picked up compared to the 2020-21 school year.

Performance in math, which declined the most last year, rebounded more than reading. And the gap between pre-pandemic and 2022 performance is smaller for younger students — whose scores declined the most in earlier results — than it is for those in the middle grades.

Lewis said she and other researchers “hit home” on the negative effects of school closures on younger students and it “could be that schools heard that message and have been leaning into those grades specifically.”

She added that there’s evidence that “it was more challenging for younger students to learn in the absence of a classroom environment” and that maybe their growth has accelerated because of the return to school.

The results should help target students for additional instruction this fall, Lewis said. She added that while students typically experience a so-called “summer slide,” past research on summer learning loss is less reliable this year because of districts’ myriad tutoring efforts and other extra academic support, due to relief funds.

The spring 2021 scores drew some districts to change how they organized students for teaching in reading and math this past school year. In School District 81, which serves Chicago’s Schiller Park neighborhood, Superintendent Kimberly Boryszewski said the needs were so great that what “used to be the exception had become the rule.”

Many students were two years below grade level, while some were still advanced. Teachers split students up into several groups to provide more individualized teaching at their level for the entire day. In one school, less than half of the second graders were meeting expectations at the beginning of the year, but by spring, 75 percent had made it.

“It tells me that model works for us,” Boryszewski said. “[Teachers] needed me to say, ‘Put the curriculum on the shelf and let’s teach the kids’ and to give them permission not to feel like they had to be on a certain page on a certain day.”

State results are mixed

The MAP results are meant to help teachers make decisions about which students need more support, but not to hold schools accountable for student performance. Such ratings will return to state report cards this year for the first time since the start of the pandemic.

Parents and educators should also pay close attention to state test results because they reflect state standards, said Scott Marion, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Assessment. As with NWEA trends, state data so far presents a mixed picture of recovery.

In Florida, the percentage of third graders reaching level 3 — or satisfactory — did not change from last year and is still below 2019’s 58%. The results in English language arts across other grades are similar.

In math, students made gains over last year, but remain below pre-pandemic levels. Across grades three through five, 62% of students reached level 3 in 2019, 52% in 2021 and 57% in 2022.

Texas officials point to additional funding for “learning acceleration” and legislation providing 30 hours of extra instruction for students below grade level as reasons why more students are meeting and mastering expectations in reading.

But according to additional notes on the data from the Texas Education Agency, roughly 10% fewer tests were taken in 2022 than in 2019 and there was an increase in students changing schools — factors that “may have contributed to the increases in proficiency rates.” If students with disabilities or English learners were among those not tested, for example, that could skew the results higher.

Tennessee was among the first to release this year’s state testing data, which shows that students are rebounding faster in reading than in math.

The early state results, Marion said, show there are no easy answers to increasing performance for all students.

“If we know how to accelerate student learning at scale, why do we see these massive gaps that have persisted and gotten worse?” he asked. “If we really knew how to do this, were we just holding back?”