Mothers of invention: Frustrated with the educational status quo and conventional parent organizing, two Latinas gave birth to a national parents union

Beth Hawkins | January 28, 2020

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

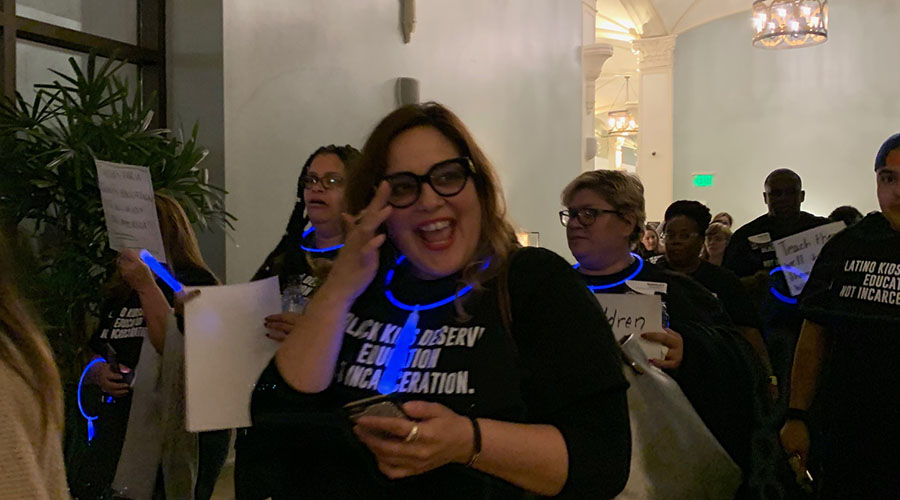

New York City English Language Arts teacher Vivett Dukes joins other parent activists in a jazz funeral for the education status quo. (Credit: Beth Hawkins)

For a moment, the issues seemed insurmountable. Some 150 parent activists, all strong-willed veterans of battles with their respective education establishments, were gathered in a New Orleans hotel ballroom trying to hammer out statements of joint belief.

It was important to arrive at precise wording, the organizers running the meeting told them, because the statement would serve, essentially, as a constitution for a National Parents Union, a network intended to exert political influence in the labor union model, which the advocates had come together to found. A foundational document, as it were, to go back to when agreement seemed elusive.

If there is a third rail in the politics of K-12 education, it’s parent organizing. Polls consistently show education is a top issue among voters, but one where candidates’ platforms frequently don’t reflect the concerns of marginalized families. Behind closed doors, state and local advocacy organizations can often be heard bemoaning their inability to galvanize parent support for their policy initiatives.

With its grassroots-up structure and ability to include many, diverse voices, a union could be a vehicle for flipping the balance of power, the meeting’s organizers hoped. Unions’ ability to incubate leadership, share effective strategies and send signals to elected officials, they suggested, could transform the way parents’ voices are raised in efforts to increase equity in public education.

In the ballroom, five beliefs — proposed starting points for a manifesto on empowering historically underserved families to advocate for their children — were projected on two screens. Table by table, parents rose to present their reactions.

I really love the idea of a national union of parents. I don’t know a lot about this group in particular, but I’m following #ParentPower2020 and listening. Also, it’s very hard to disagree with any part of their statement of purpose. pic.twitter.com/W9k3FUqSvL

— Tom Rademacher (@MrTomRad) January 18, 2020

A woman speaking for a group of Latinos pointed out that the word “unapologetically” doesn’t translate into Spanish.

At another table, participants wanted a stronger call for equity, suggesting instead, “There must be liberty, justice and equity in education for all children.”

Great, responded a woman in a different group — but how to incorporate the needs of children with disabilities: “Should it say systems of oppression?”

The Spanish-dominant table agreed, yet pushed back: “Keep the sentences simple because everything takes 20 percent more words in Spanish.”

Madres unidas jamás serán vencidas — Mothers, united, will never be defeated

The National Parents Union is the brainchild of two Latina mothers — organizers at different times, for the Service Employees International Union, Obama for America, Green Dot Public Schools and Massachusetts Parents United — who hope the labor union model, with its emphasis on collective efficacy and member training, can strengthen isolated parent groups to push for change in education nationwide.

The parents, guardians and grandparents they invited to found the union represented 100 organizations in 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Ethnically, racially and politically diverse, the activists had spent the previous 36 hours getting to know the most pressing issues in one another’s communities before sitting down to the messy work of trying to agree, down to the placement of commas, on exactly what all 150 participants believe their new union stands for.

Among them was Vivett Dukes, a New York City seventh-grade English teacher who brought the room to tears talking about her formerly incarcerated husband’s efforts to parent from prison, and the misassumptions his child confronted in school.

John Dukes sent his regrets. At the last minute, his parole officer had denied him permission to travel.

Preceded by a presentation on union history and organizational structure, the wordsmithing had been underway for some time when the passive construction of a proposed statement on resources and parent skill development stumped the participants.

Dukes stood. “I think what people are struggling with is the prepositional phrase at the end of the sentence,” she said, reading the last statement up for finessing with a teacher’s “I need eyes on me” voice. “If you moved it to the front, it would read less negatively.”

Unanimous approval of the version that somehow incorporates 120 people’s strong and sometimes divergent opinions on everything from comma placement to the nature of racism. pic.twitter.com/u0wLQhviux

— Beth Hawkins (@beth_hawkins) January 18, 2020

The room burst into spontaneous applause. By unanimous vote, shortly thereafter, the National Parents Union was born. Founders Keri Rodrigues and Alma Marquez were voted into three-year terms as inaugural president and secretary-treasurer, respectively. Seconds later, thorny questions about the distribution of power within the new organization were raised. Ink still metaphorically wet, the belief statements came in handy in reaching agreement on how the issue would be addressed.

https://twitter.com/radiokeri/status/1218658586760556545?s=11

Parent activism at the school and district level is often met with hostility, which as often as not means families simply disappear from a school that’s not working for their children. Particularly in poor communities, when parents do coalesce, it’s usually around a flashpoint. But using a crisis as a springboard to something sustainable is elusive.

Marquez and Rodrigues had had disappointing experiences with education, both as parents and students, and with advocacy groups — frequently run by white men — that wanted a parent base to tap for visible support but were less interested in grassroots voices between policy pushes. Both had used that frustration to jump-start parent networks in their communities: Rodrigues, Massachusetts Parents United; and Marquez, who lives in Southern California, La Comadre.

At Green Dot Public Schools in Los Angeles, Marquez organized parents to help grow the network of unionized public charter schools from four schools to 18, then went on to co-found the 12-chapter Los Angeles Parents Union.

On the East Coast, Rodrigues traveled as an SEIU organizer, developing a reputation for staging creative protests of businesses the union wanted to pressure, such as performing a Britney Spears send-up at a Bob Evans restaurant and staging a flash mob inside a bank. Within two years of its founding, her Massachusetts Parents United had organized 10,000 parents.

Two years ago, Marquez’s sister insisted that the two meet. “We started planning on our Hilton points,” Marquez told parents at the launch event. “We live across the country, so we’d go and meet in the middle.”

The structure of a trade union, the two concluded, had the potential to both harness parents’ energy and provide a way to force the “grasstops” — the professional advocates often focused on school governance, standards and accountability and other high-level ideas — to listen to parents’ immediate, on-the-ground needs.

Unions are also peerless, they noted, at helping passionate individuals develop an understanding of political power, as well as how and where to push elected officials to take up members’ priorities. And having local, state, regional and national-level offices allows different parts of the organization to come to one another’s aid, whether it’s for technical help or for displays of political might such as the teachers union Red for Ed strikes and demonstrations that have swept numerous states.

“Lots of parents do great work but still need professional development,” said Rodrigues. “Parents don’t have the expertise to set up nonprofits, to secure funding. There’s got to be a group of people who say, ‘Oh, I know how to do that. I can help.’”

In addition to often lacking organizing capacity, low-income parents and families of students with disabilities frequently find that their children’s schools write off their advocacy for their kids as adversarial rather than acknowledging it as parental involvement.

“What is so heartbreaking about this work is seeing parents constantly indicted for not wanting to be involved,” said Rodrigues. “We are talked to as if we are not capable of independent thought.

“What [schools] do not understand is that parents are survivors of the education system,” she added. “Parents do not want to engage and stay in communication with people who are disrespectful.”

Ideologies notwithstanding, education organizations have tended to focus on policies and practices they think will create better schools, such as higher academic standards, teacher effectiveness and compensation, and expanding — or curtailing — school choice.

It’s uncertain, however, whether parents understand how these issues might affect their families. Much of the time, marginalized parents are far more focused on things like gun violence in their neighborhood or fighting to get a child with a disability or mental health needs out of isolation.

Better, the union’s founders felt, to start with parents’ demands than technocrats’ proposed solutions. As Rodrigues put it, “We’re not going to march for governance models.”

‘The only way it will work is if we authentically hear from parents’

Marquez and Rodrigues raised seed money and funding for the recent convening from several philanthropies that fund education initiatives: The Walton Family Foundation; EdChoice; the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools; National School Choice Week; the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation; and The City Fund, which in turn receives funding from Walton, the Hastings Fund, the Arnold Foundation (now Arnold Ventures), the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Ballmer Group.

No surprise, then, that the launch event focused not on specific policies but, on the first day, on the nature of activism, and on the second, on why a union is a powerful vehicle for expressing that activism.

Participants heard from Felipe Luciano, founder of the civil-rights-era Young Lords Party; Ilyasah Shabazz, activist daughter of Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz; and a host of other speakers. Colleen Cook, president of the National Coalition for Public School Options, talked about the brutal murder of her stepdaughter and grandchild last fall. Christina Laster, education chair of the South Riverside County NAACP, in southern California, delivered a presentation on “How to Be Disruptive,” while former United Nations peacekeeper Steve Vigil spoke on civil disobedience.

The former president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, Paul Toner, kicked off the organizing portion of the program with a history of unionism and a primer on how to unite diverse voices behind an agenda. Toner is now senior director of national policy, partnerships and the northeast region of Teach Plus, a national teacher leadership incubator.

And a protest of sorts was staged: a signature New Orleans jazz funeral, in which a brass band, costumed stilt-walkers and a police escort led sign-carrying parents out of their hotel meeting room and down Bourbon Street. The funeral was for the status quo.

Organizers had initially planned to have the new union’s delegates vote on a presidential endorsement. Platforms, summarized by an outside researcher, were on display. But noting the frequency with which candidates claim to have the black vote, only to disappear from those communities after they are elected, a number of parents asked the leaders to reconsider.

One of the union’s first decisions, then, was to vote for which elements of the candidates’ platforms were their highest priorities.

The National Parents Union is not the first effort to attempt to give parents the type of collective agency enjoyed by various trades and professions. Indeed, teachers unions have attempted to raise parent armies. Past efforts, however, mostly have foundered as hot-button issues resolve or parents, disaffected with the organizations’ leadership, move on.

This effort will be different, Rodrigues said, because the National Parents Union will be structured for bottom-up engagement. Striking while the energy is high, she and Marquez have begun mapping the resources for each of the 100 new affiliate organizations, located in every state, and are asking members for input in creating six regional councils and one national parent council.

“I need their approval, frankly, because it is a democratically run union,” said Rodrigues. “The only way it will work is if we authentically want to hear from parents and give them space to speak their truth and their context and know they are going to be heard.”

Chosen the new effort’s national Most Valuable Player at a ceremony concluding the event, Khulia Pringle, a family organizer with the newly formed Minnesota Parent Union, said she’s eager to tap the organization for specific strategies and materials she can use, ideally in her parents’ campaign to get Minneapolis Public Schools to agree to priority enrollment for marginalized children in its highest-performing schools.

“I am hopeful that this is going to be different,” she said. “I am hopeful that parents are truly going to be in the driver’s seat.”

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation, The City Fund and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation provide financial support to the National Parents Union and The 74.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.