New California legislation would mandate ‘science of reading’ to improve child literacy

Angelina Hicks | March 19, 2024

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

With a majority of California third graders unable to read at grade level, proposed legislation would mandate teachers use the phonics-based science of reading.

Assemblymember Blanca Rubio (D-Baldwin Park) and 13 co-authors have proposed a bill that would update the state’s English curriculum with the science of reading – research that has found the best way to teach reading is through phonics, phonemic awareness, oral reading fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

The bill calls for more instructional materials and curriculum for classrooms to align with the science of reading. It also emphasizes the need for increased professional development for teachers and more progress monitoring for students struggling with reading.

“All English language arts, English language development, and reading textbooks and instructional materials for transitional kindergarten, kindergarten, and any of grades 1 to 8, inclusive, shall adhere to the science of reading,” reads the bill which was submitted to the Assembly’s education and higher education committee in February.

Schools would require a waiver if educators wanted to use instructional materials that aren’t aligned with the science of reading. It is supported by 12 Democrats and two Republicans in the state assembly.

A December 2023 policy brief by EdVoice, Decoding Dyslexia CA and Families In Schools found 60% of California students aren’t reading at grade level skills by the time they reach third grade.

“As an educator, I have firsthand knowledge of the struggles instructors face to ensure their students know how to read,” Rubio said in a statement. “California teachers work tirelessly to better the success of each student. However, California is failing its students, especially diverse students from low-income families.”

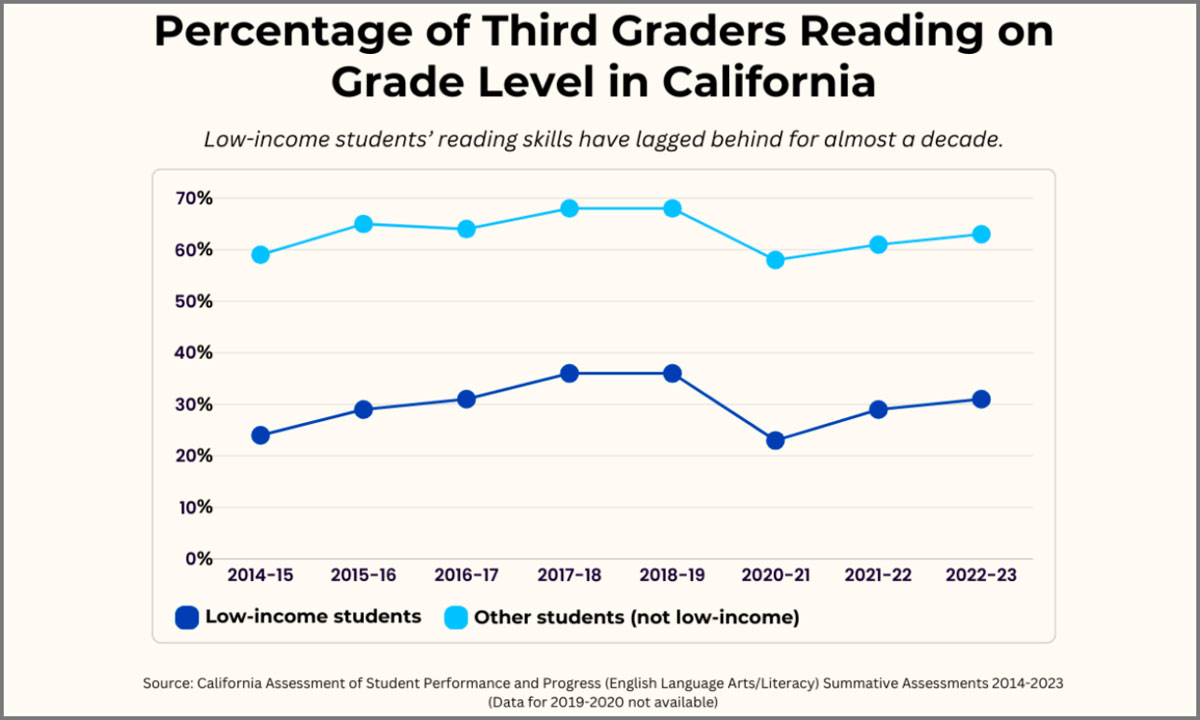

In the 2022-2023 school year, 31% of third-graders in low-income families were reading on grade level. For students not considered low-income, 63% were reading on grade level.

That trend has been steady for nearly a decade, with low-income students underperforming in reading tests every year since at least 2014.

“Historically, we’ve seen low performance in literacy in California,” said Eugenia Mora-Flores, a professor and an assistant dean at USC’s Rossier School of Education. “It’s not surprising, actually. We’ve definitely seen low literacy performance in large districts like L.A. Unified and others where we have students that are not performing at grade level.”

To address low scores, legislators want teachers to use the science of reading. Some schools across the state already use this method when teaching students. Others use “whole language,” which focuses on the meanings of words instead of breaking them down into pieces.

That’s different from the science of reading, which relies on phonics and encourages students to learn how letter combinations sound out loud to decode words based on their spellings.

“[The science of reading] is an acknowledgment that kids will learn to read if they can learn the letters, sound them out and gradually pick up on fluency over time,” said Pedro Noguera, dean of USC’s education school. “If you don’t read at proficiency by third grade, then you’re in trouble because everything in school is literacy-based. After learning to read, then you read to learn, right? If you can’t read a math problem, you can’t do the math.”

Noguera said a mandate alone won’t solve California’s literacy problem without looking at the bigger picture when it comes to teaching kids to read.

“If we just focus on the science of reading, on phonics, we’re also missing the point, right?” Noguera said. “If we want kids to be good readers, phonics is not going to take them there. They need good books. They need a comprehensive approach to literacy.”

“All English language arts, English language development, and reading textbooks and instructional materials for transitional kindergarten, kindergarten, and any of grades 1 to 8, inclusive, shall adhere to the science of reading,” the bill reads.

Dozens of states across the country have already implemented laws enforcing the science of reading.

Last year, Indiana mandated that schools must use the science of reading by fall 2024. So have legislators in Michigan, Utah, Kansas, Oklahoma, North Dakota, Pennsylvania and the Carolinas, among others.

In a state with one of the lowest literacy rates in the country, Mora-Flores said it will come down to how well the mandate is implemented across California.

“In some ways, [the bill] can be seen as a good thing because it’s saying, at minimum, we all need to make sure kids are getting something, and you’re going to be held accountable to it because now it’s policy,” Mora-Flores said. “On the other side of that, it’s really going to come down to the quality of translation and implementation.”

This article is part of a collaboration between The 74 and the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Angelina Hicks is a reporting fellow for Voice of OC, a nonprofit news outlet in Orange County, CA. She’s currently a master’s student at USC Annenberg and managing editor at Annenberg Media.