New Research: Students in majority-Black schools had been 9 months behind their white peers. Now, the gap is a full 12 months

Beth Hawkins | February 23, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

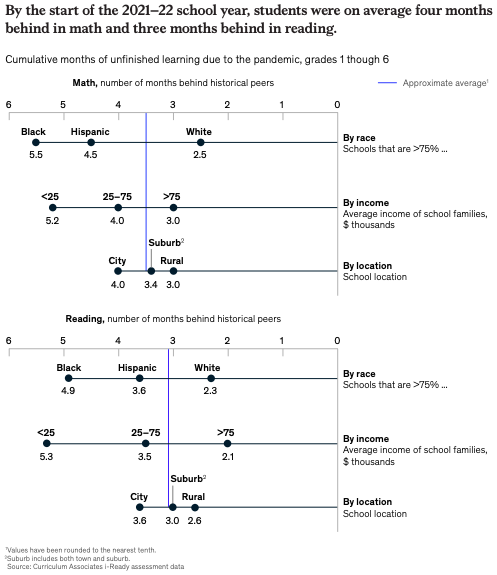

Students in majority-Black schools are now a full 12 months behind those in mostly white schools, widening the achievement gap by a third, according to a new analysis by McKinsey & Co. Overall, students are four months behind in math and three in reading compared with years past, but those totals hide wide disparities.

At the same time, the range of students’ academic needs teachers must address within a single classroom has widened, with the share of children at or above grade level in math falling by 6 percentage points and the number two or more grade levels behind increasing by 9 points. As a result, the number of students far below grade level in a hypothetical math class of 30 fourth graders has risen from eight to 11.

The researchers based their conclusions on Curriculum Associates’s i-Ready assessments administered this fall in person to 3 million students in grades 1 to 6 in all 50 states. They compared the results with exam scores from a comparable set of schools in 2017, 2018 and 2019. In addition, they used data from Burbio and from McKinsey’s own parent surveys to show that while there is less disruption to learning than last spring, a variety of factors are limiting students’ time in class just when they need it the most.

Overall, students have made up about a month of unfinished learning compared with last spring, notes the report, “COVID-19 and Education: An Emerging K-Shaped Recovery.” But that rebound, too, is inequitable.

In schools where enrollment is 75 percent or more Black, students are 5.5 months behind in math and nearly as much in reading. In majority Latino schools, they are 4.5 months behind in math, and in white schools, 2.5 months. Low-income and urban schools are experiencing similar disparities.

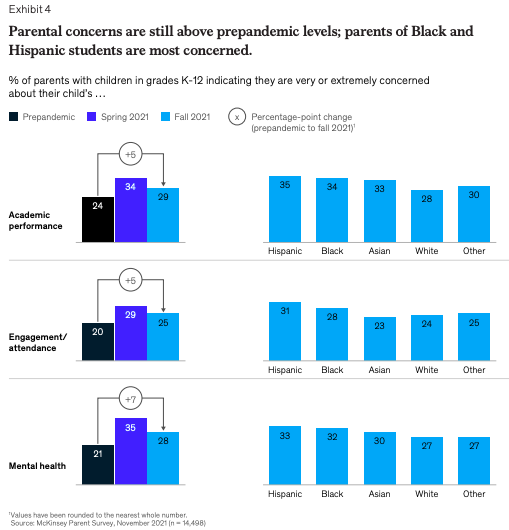

Parents’ perceptions of their children’s well-being have rebounded somewhat since a June 2021 spike, but concerns remain. Compared with pre-pandemic surveys, the number of families with fears about academic achievement and student attendance and engagement is up 5 percent, with an increase of 7 percent in those reporting mental health concerns.

Parent reports of their own children’s absenteeism are up 2.7 times over pre-pandemic levels, which the researchers say is likely a dramatic underestimate. Up to one third of students may be chronically absent this year, defined as 15 or more days not in school.

“Nearly half of Cleveland’s students are on track to be chronically absent this school year,” the report notes. “Low-income students, who often lack access to resources to make up for lost instruction in the classroom and who are more likely to experience ongoing attendance barriers, are 1.6 times more likely to be missing multiple days of school than their high-income peers.”

According to Burbio, 9 percent of public-school students have been affected by a school closure this academic year, with 54 percent of U.S. students receiving some form of virtual instruction during the disruption. In its canvass of parents, McKinsey found that of students who chose to attend fully in-person learning this fall, only 83 percent attended 10 full days during the two weeks the survey was in the field.

Confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases account for just 12 percent of closure days, researchers found, with 50 percent of closures consisting primarily of single-day breaks school districts have taken to support student and staff mental health and another 13 percent caused by staff shortages. Parents of Black and Latino students were most likely to report that school closures were the cause of their children’s interrupted in-person learning.

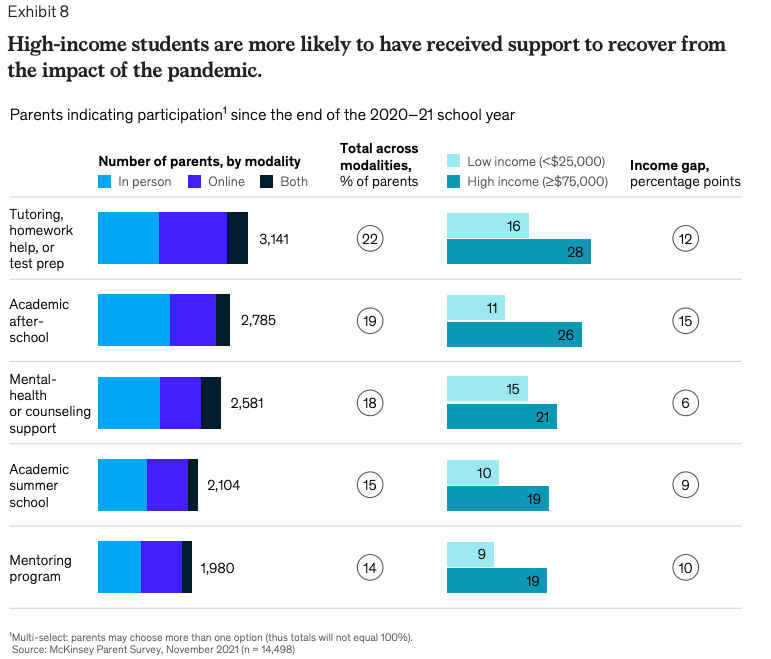

Finally, researchers found gaps by income level in the likelihood a student has received academic or social-emotional pandemic recovery support and a disconnect between the services parents say they want for their children and those included in school districts’ plans for spending federal stimulus funds.

Districts are budgeting about a fifth of their third-round funding for summer school, while only 17 percent of parents are interested in this option. By contrast, 29 percent of parents want tutoring, but just 7 percent of academic recovery funds are directed to this option.