New survey: As afterschool participation falls to lowest rates since 2009, California is a promising outlier in meeting parental demand

Linda Jacobson | January 19, 2021

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

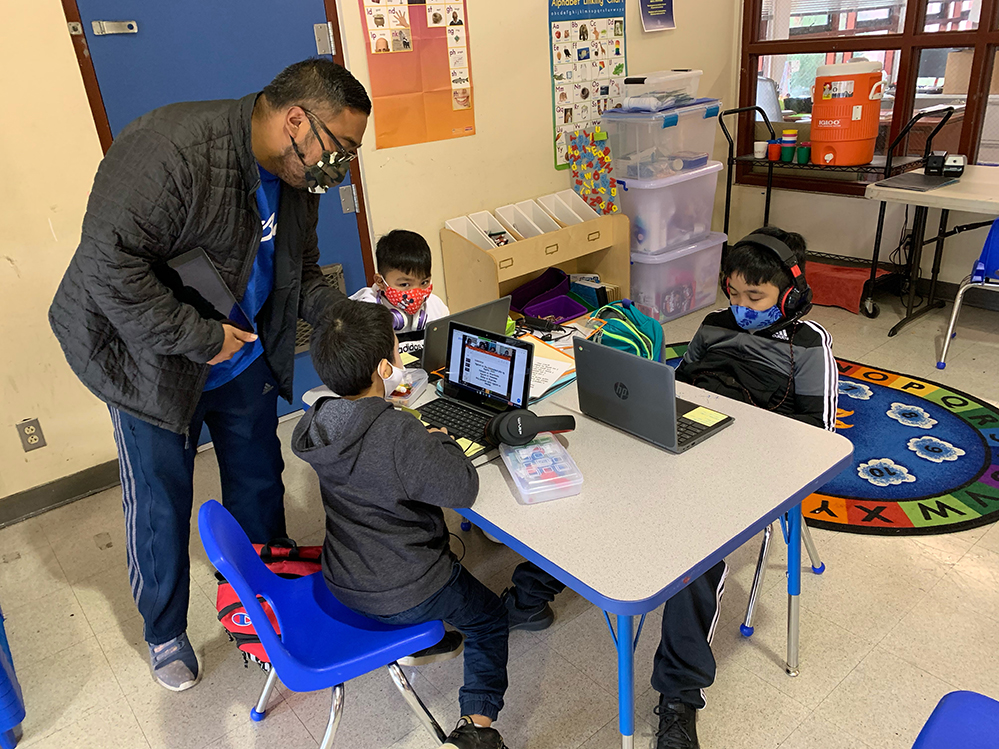

Josh Tolliver, a student at Bessie Carmichael Elementary School, works on his laptop at the Gene Friend Recreation Center in San Francisco. (United Playaz)

For every child in an afterschool program in the U.S., three are waiting for a spot, according to new data released Tuesday. And the demand for programs has increased by 60 percent since 2004.

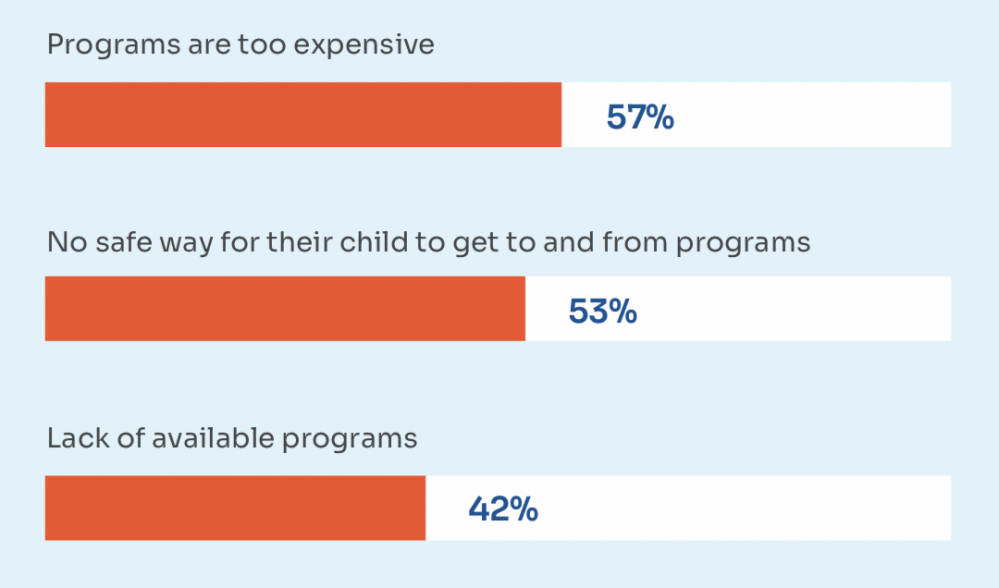

More than half of the 31,000 respondents to the Afterschool Alliance’s “America After 3 p.m.” survey said cost is what’s keeping their children out of afterschool programs, which average about $100 per week. The results show higher-income families spend roughly $3,600 per year on out-of-school-time activities, compared to $700 per year for low-income families. A lack of transportation and available programs in their neighborhoods were other common barriers.

The 7.8 million students enrolled in afterschool programs represent the lowest participation since 2009, down sharply from a peak of 10 million students in 2014. And fewer students from low-income households are involved: 2.7 million this year, compared to 4.6 million six years ago.

The report identifies California, Florida and Missouri among the 10 states with greater participation rates. The top states also serve more low-income children and have higher parent satisfaction rates. Nationally, the survey also shows that almost 80 percent of parents say afterschool programs allow them to remain employed or work longer hours.

The top three reasons why parents don’t enroll their children in afterschool programs. (Afterschool Alliance and Edge Research)

The new data comes as providers that have traditionally offered their services after 3 p.m. on school days are expanding their programs to become hubs and pods for students during remote learning. Others, such as After-School All-Stars in Washington, D.C., have ramped up virtual classes — including tutoring, visual arts, cooking, and dance — to provide students with additional activities after their distance learning time.

“I think we are playing a huge role right now,” said Jodi Grant, executive director of the Alliance. She added that as long as schools remain closed or partially open because of the pandemic, the need for learning centers and hubs will continue “as we enter recovery.”

In November, the Alliance released results from 1,445 providers showing the percentage of afterschool programs that are open in person has grown since the beginning of the pandemic, from 19 percent in the spring to 68 percent now. In addition, a quarter have extended their schedules to accommodate families during school hours.

They include United Playaz in San Francisco, a violence prevention and enrichment program that offers six pods, each with 14 students, across three sites. The hubs run all day, and staff members also help prepare meals, deliver groceries to families, and troubleshoot school technology issues, said Heather Phillips, director of programs.

“Just like our students, staff sometimes struggle with how strange this time is,” she said. “Things like pajama day, decorating their pod spaces, and even selecting a student of the week … help the situation feel more like a ‘normal’ school year.”

The program sets an example for how to “think about extended learning time beyond the walls of school,” said Stacey Wang, CEO of the San Francisco Education Fund.

Ephraim Basco Jr, a K-2 program coordinator with the United Playaz afterschool program, helps students at a learning hub site at the Gene Friend Recreation Center in San Francisco. (United Playaz)

But because of the pandemic, many providers still don’t have access to in-person spaces. In Connecticut, Before and After School Extended Services, or BASES, is normally a school-based program that runs in seven school districts. The program adjusts its hours depending on whether school districts operate in-person, virtually, or a hybrid of the two.

“The superintendents have struggled with the optics of closing schools but allowing a program to come into the school anyway,” said Sarah Moran, department director for BASES. “This is a challenge for us. We have enough staff that want to work but we have not been able to consistently provide hours.”

Students at Head O’Meadow Elementary School in Newton, Connecticut complete an obstacle course in a BASES afterschool program. (Before and After School Extended Services)

Federal support uncertain

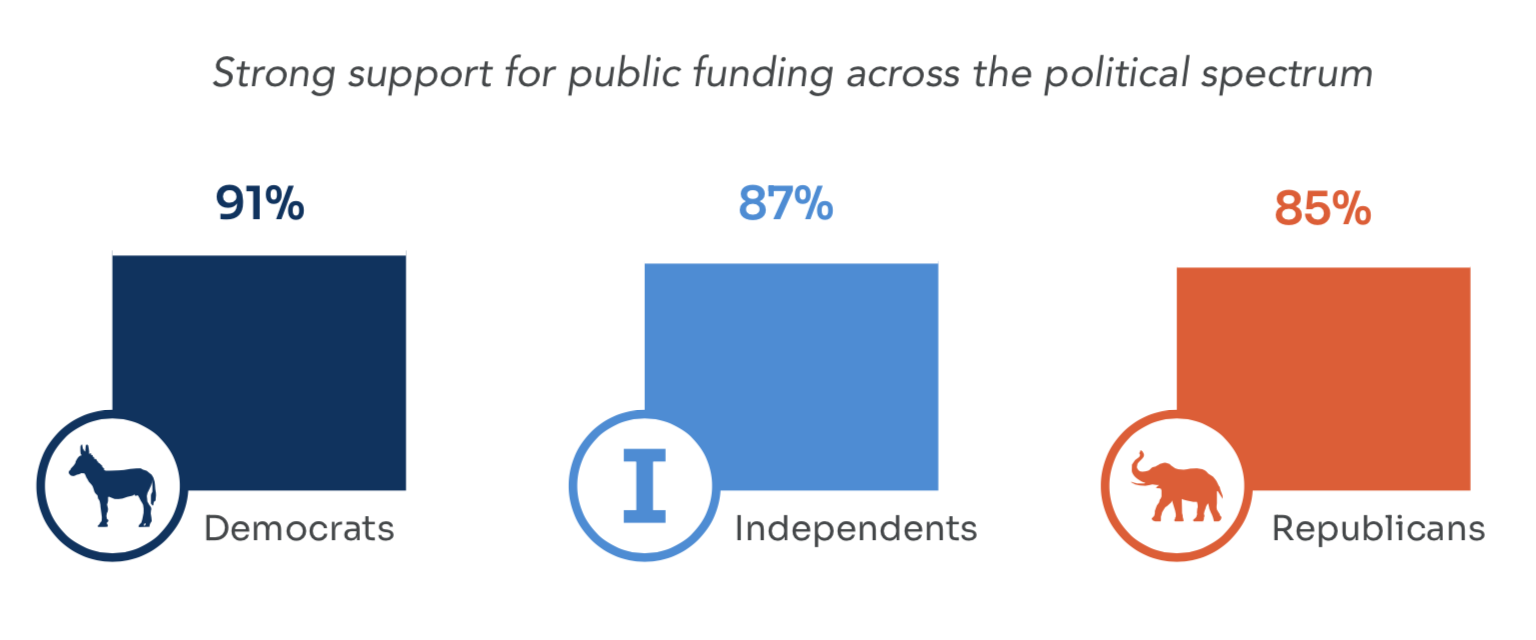

Advocates have also focused their attention on Washington, asking for flexibility in the hours that federally funded programs can operate and lobbying for additional money to serve more low-income children and help providers stay in business.

In September, the U.S. Department of Education issued a waiver for states allowing programs funded through the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program to operate during school hours as long as buildings are closed.

But advocates want Congress to replace the waiver with legislation. In September, the House passed the 21st Century Community Learning Centers Coronavirus Relief Act, which would replace the waiver process.

In the Senate, Republican Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Democrat Tina Smith of Minnesota have introduced companion legislation that would allow the same flexibility, but also add $1.2 billion for additional staff, rental space and other expenses incurred during the current crisis. The bill is now in the Senate education committee. Advocates have called for $6.2 billion in funding for afterschool programs to accommodate families during this unpredictable school year.

The Afterschool Alliance survey finds bipartisan support for afterschool programs. (Afterschool Alliance and Edge Research)

Providers say they also want to be more involved in discussions related to reopening schools.

“I understand the school system is really focused on teaching kids and the academic burden in a digital time is heavy,” said Daniela Grigioni, executive director of After-School All-Stars in Washington, D.C. “But there is no inclusion, cooperation, or consideration for the out-of-school-time sector. We have more capacity for service, … deep community roots and outreach, and could do more given the chance.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.