‘Nudging’ students to college matriculation: How KIPP schools are using text messages to combat summer melt and ensure alumni make it to their first day on campus

Lauren Costantino | August 12, 2019

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Photo by Patrick Hertzog/AFP/Getty Images

While cell phones in the classroom can detract from student learning, one school program is taking advantage of the fact that a generation of digital natives can’t stay off their phones.

KIPP Public Charter Schools, a national charter school network of more than 200 schools, rolled out the National Nudge Texting Pilot this summer. The program seeks to combat a national phenomenon known as “summer melt,” in which thousands of college-accepted teens fall off the map in the summer months after high school graduation, and ultimately never matriculate at college. Summer melt is not to be confused with “summer slide.”

The summer campaign will send out automated “nudges” in the form of text messages — twice a week — to help KIPP’s ever growing number of students keep track of the many tasks — like completing housing applications and paying student activity fees — that they’re required to complete before getting to campus in the fall. About 10 percent of KIPP’s graduates “melt away” before making it to the colleges in which they’re enrolled.

“We don’t want to overburden our students with a ton of messages,” said Nadila Yusuf, Senior Manager of College Persistence for KIPP Through College. “We want to pick the most critical messages so that we actually make an impact.”

Various studies peg summer melt as affecting anywhere from 10 percent to 40 percent of college-bound students each year, according to the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University. The highest rates of summer melt are found among students from low-income families and first-generation students — those who are the first in their families to go to college. Summer melt is so well known among institutions of higher education that some even factor the predicted loss of students in to their acceptance rates.

Financial aid is a major, two-pronged hurdle for students who have little to no experience navigating the Free Application for Federal Student Aid forms. First, low-income families are not able to absorb unmet financial needs as easily as more affluent families can, so students may fall off in the summer when they discover that they are unable to afford tuition and fees, said researcher Lindsay Page, author of Summer Melt: Supporting Low-Income Students Through the Transition to College.

But a second, under-the-radar obstacle for students in need of financial aid is that the application process can be complicated and long, and any lapse in completing paperwork can mean the difference of tens of thousands of dollars in aid — and thus, the ability to go to college at all. This is particularly acute for KIPP, whose schools educate over 100,000 students, 88 percent of whom are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, a commonly used metric for categorizing economically disadvantaged students (but is starting to become a less reliable data point).

Other students “melt away” from a failure to complete administrative tasks required by colleges, such as attending orientation, finding health insurance, taking placement exams, selecting classes and paying for tuition, housing and student fees. For many students, it’s these tasks, which may come more naturally to their more affluent or experienced peers, that become significant barriers to their future college success.

“Nudging” toward success

Based on Nudge Theory — developed by Nobel Prize-winning economist Richard Thaler — schools, like KIPP, are starting to use small, inexpensive interventions called “nudges” to help guide a student’s summer behavior.

Nudging a student over the summer typically means sending an organized set of prompts to students that help them complete requisite summer tasks. The nudges can be sent via text, phone call, email, WhatsApp or other digital methods and may remind a student that a financial aid form is due soon, or send a link explaining how to set up their college email account.

Studies have shown that students who receive any kind of nudge over the summer — whether from guidance counselors or chatbots — are more likely to successfully enroll in college than those who don’t receive any form of intervention. One recent study, by the University of Virginia’s Benjamin L. Castleman and the University of Pittsburgh’s Lindsay C. Page, included nearly 5,000 low-income students. The researchers found that 70 percent to 72 percent of students who received a nudge intervention — whether from a peer mentor or via a text message — successfully enrolled in college, compared with 68 percent to 70 percent of students who did not.

“We find that this kind of timely summer outreach — with reminders of what students need to be doing, and a streamlined offer of help when students have questions or issues — that this leads to positive and statistically significant impact on timely enrollment,” Page said.

She added that text messages seem to be a more accessible way for students of this generation to communicate. In 2011, Page’s team performed a nudge study in which counselors were first calling and emailing students as methods of outreach, but switched to texting midway through when students weren’t as responsive to those more traditional methods of communication.

‘The victims of summer melt are students that wanted to go to college’

KIPP’s texting pilot is unlike other past nudge campaigns in part due to its sheer breadth. During the 18-month pilot, KIPP will send approximately two nudge texts per week to participating alumni in eight different regions including Washington D.C, New Orleans, Los Angeles, Memphis, New Jersey, Chicago, Houston and Dallas. Nearly 950 students have opted in to the campaign since it launched in early June, and KIPP officials are expecting even more to sign on throughout the summer.

The nudge campaign is a natural step for KIPP, whose college persistence program uses an ongoing, rigorous process to provide students with one-on-one support before and during their time in college. KIPP uses a data tracking system that is unlike any other charter school network in the country, and they are fervent believers in following their students’ graduation success from the ninth grade instead of the more common 12th grade.

KIPP Persistence Framework 09092016 (Text)

Another unique aspect of KIPP’s nudge program: its dynamic and adaptive nature. In March, the KIPP Through College team got together to consider the challenges students were experiencing at their institutions of higher education, and what KIPP could do to get ahead of them. The team mapped out a schedule of the top college-preparation priorities for each month of the summer, then developed a script for the text messages based on input from alumni advisors and students.

Feedback from each region is already informing future decisions, Yusuf said. Every two weeks, the KIPP Through College team meets with leaders from each pilot region to talk about what kind of data they’re getting from the chatbot and how counselors are responding to the issues students are having.

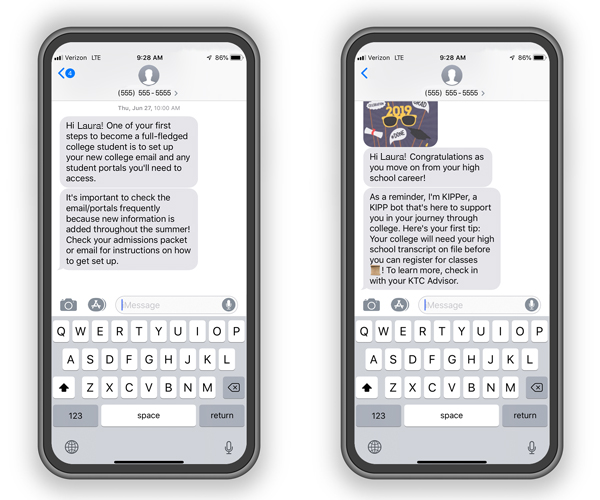

Artificial intelligence technology is also a large contributor to KIPP’s ability to continuously improve the program and tailor it to students’ needs. The network selected AdmitHub as its nudge technology vendor, which uses “natural language processing,” Yusuf said. That allows the chatbot, named “KIPPer,” to offer more detailed and informative responses than just “yes” or “no.”

Yusuf added that AdmitHub has collaborated with other universities to develop a detailed “knowledge base” for the bot, so KIPPer is able to send out more college-specific reminders. KIPPer can, for example, tell students how to access their colleges’ unique email portals.

These college-specific answers are “giving some more details that maybe the alumni advisor might not be able to do immediately,” Yusuf said.

Of course, KIPPer won’t have all the answers. When the chatbot receives a request from a student that it cannot accurately answer, the question will get passed to a “human escalation inbox,” Yusuf explained. Each region’s alumni advisors will then assist students with counseling needs outside of the chatbot’s ability. These advisors are also familiar with the students, as they are the very ones who work with the teens from high school graduation through college.

Other schools across the country have found their own approaches to nudging that are most effective for their students. In 2016, Kalamazoo County, Michigan partnered with College and Career Action Network to launch a similar summer melt prevention campaign, in which high school counselors in local school districts nudged students throughout the summer. Although all students who were accepted to either Kalamazoo Valley Community College or Western Michigan University were allowed to participate, the pilot targeted students who were economically disadvantaged as well as first-generation college students.

“We really wanted to go after students that we felt were more vulnerable to summer melt,” said Evan Pauken, KVCC’s director of retention and completion. “We didn’t want to put in place a technology that was going to just remind all students of blanket information, we really wanted some personal touch.”

The planning team felt that high school counselors who had existing relationships with students were the best people to both motivate and guide students across the finish line. Counselors were advised to meet in-person with their students at least twice over the summer. They also communicated with the students regularly through email, Facebook messenger and otherwise. Some counselors were so invested in their students’ success that they drove the teens to the bank for financial deposits or test-rode bus routes with their students to ensure they knew how to make it to school in the fall.

Although the size of the study was small — just 66 students took part — Kalamazoo County found that students who participated in the summer melt prevention program were 1.25 times more likely than students who did not receive any interventions to complete at least one semester of classes at KVCC or WMU the year after their high school graduation.

“Above all else, the victims of summer melt are students that wanted to go to college,” Pauken said. ”And for whatever reason, something happens throughout the summer that prevented them [from] doing that.”

The work doesn’t end there

The KIPP Through College team is thinking long-term about how to support students who are most vulnerable to summer melt. Students who have second thoughts about their enrollment plans may need more counseling than the bot can provide. That’s why, in the fall, KIPP will be sending out a survey to two-year community college students to find out if they are fully enrolled or having any feelings of doubt.

“We’re going to be asking students, ‘How are you feeling about college? Press one if you’re super excited and already there, press two if you’re unsure and not fully committed,’” Yusuf said.

She added that her team will be able to download the survey results and follow up with students who answered that they are unsure or that they’re not attending college anymore. The KIPP Through College counselors will then be able to step in and help figure out where the students need more support — even if it’s something more long-term, such as promoting positive mental-health practices or cultivating a sense of belonging in college.

“The big idea here is that if we can get data from our students more quickly and efficiently through nudge— such as whether they’ve been able to purchase all of their required books, or whether they need help navigating FAFSA verification — we can intervene with those who need it much more quickly,” Yusuf said in an email.

For KIPP, the national nudge campaign is just another tool to help advisors and counselors support students most efficiently and effectively.

“Our advisors will spend less time trying to figure out who needs assistance, and more time actually providing assistance to those who need it, when they need it,” Yusuf said.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.