One of LA’s first inner-city charter schools celebrates 20 years — and is proud to keep ‘Watts’ in its name

Mike Szymanski | September 11, 2017

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

- Cynthia Clark’s class.

- Outside at the elementary school.

- Students of Watts Learning Center.

- Construction of the new building in spring 2017.

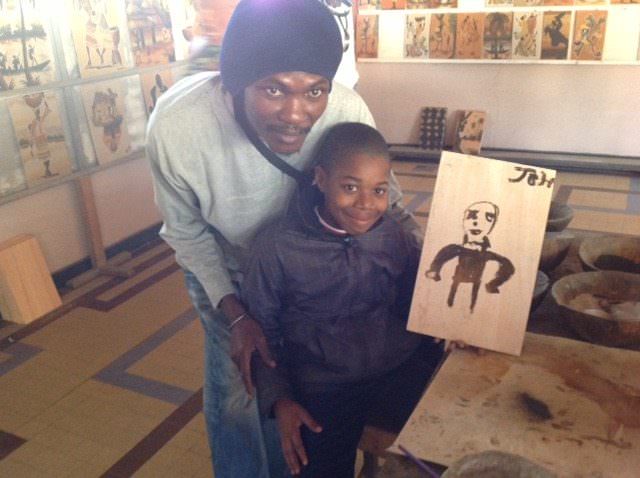

- A trip to Africa with the students.

- Sandra Fisher with students

- Teacher Cynthia Clark

- Ashley Person wanted to work at the school after interning.

- The Fishers take students to Kenya.

- The new building opens

- Students greet Sandra Fisher.

- The middle school campus at Dymally High.

- Sima Aleahmad holds a check-in with her students.

- Students outside at the elementary school

- Part of the school is a converted church.

*UPDATED

When Gene Fisher opened an independent public charter school in September 1997 in Watts, it shared a one-room bungalow in a housing project with the Urban League State Preschool.

Fisher quickly realized that recruiting kids from rival gangs was not going to happen.

So he moved his two kindergarten students and tiny staff, ending up in an abandoned church in the shadows of the 110 Freeway and the jets coming in low to LAX. This month, the school community celebrates its 20th anniversary expanding into a new two-story building — still in Watts, only a mile from where they began.

Watts Learning Center — LA Unified’s seventh independent charter elementary school and one of the first inner-city charters in Los Angeles — continues to be a model school in a neighborhood where just heading to school can be dangerous. More than a dozen other charter schools approved around the same time at LA Unified have since closed down or converted back to district schools.

It’s faced big struggles since the beginning. Watts opened a middle school in 2008 that LA Unified nearly shut down in 2013 after questioning whether it had a “sound educational program.” But the middle school is now on a new campus and thriving.

The elementary school became a California Distinguished School in 2004 and Charter School of the Year in 2007, and some of its graduates have gone on to full-ride scholarships at such universities as USC.

They did it by pulling together a team that believed they could bring quality education to one of the most disenfranchised communities in Los Angeles. And they insisted on keeping Watts in the name.

• Read more about how high-performing public charter schools got their start in California in The Founders by Richard Whitmire.

Fisher started with only three teachers, an office manager, a principal, and two kindergarten students. Watts Learning Center now has 53 teachers and instructional aides, 89 staff and foster grandparents listed on their staff rosters, and 780 students on two campuses. There are nearly 400 students in kindergarten through sixth-grade at Watts Learning Center Elementary School at 310 W. 95th St., and 380 at the Watts Learning Center Middle School on the campus of Dymally High School at 8800 S. San Pedro St.

The elementary school has 51 percent black students and 47 percent Latino students, and the middle school is 16 percent black and 83 percent Latino. All of the students are eligible for free lunch.

“Some educational institutions have said that it’s a challenge to educate black youth, particularly young men, but we don’t see it that way, we see it as an opportunity,” Fisher said. “We understand the community and the struggles these boys have in their everyday life and so we figure out how educational values fit into their lives and improve the community as a whole.”

Fisher acknowledged that the neighborhood has been tainted with a history of unrest, crime, and poverty, and said, “We never want to forget the community, so keeping Watts in the name of our school is important to us.”

“We chose the name Watts. It’s an under-resourced community, and people know it,” Fisher said. “Our charter school allows us to implement a belief system to change the narrative of the neighborhood’s reputation with the Watts riots and the Watts rebellion.”

‘WE CAN EMPHASIZE THE GOOD’

Walking through his lime green-painted campus with the children playing in the sun, Fisher said, “We are here with beautiful weather, good transportation, entertainment, fun, and beaches. People come to Southern California, but not to Watts. We can emphasize the good and change the narrative of our neighborhood.”

But there’s still a reputation that lingers. When the head of a teacher prep program at a Michigan college tells prospective teachers about internships in Watts, it sends a shiver through the students and their parents. Inevitably, they recall the 1992 riots that left 50 dead after the acquittal of four white police officers accused of beating a black motorist. Before that, it was the center of a rebellion after a black driver was pulled over by police in 1965. Thirty-four people died.

“When I tell the parents that the school is located in Watts, I can hear the phone fall out of their hands, and that reaction is across racial and ethnic groups,” said John A. Yelding, chair of the Education Department at Hope College, a small liberal arts Christian college in Holland, Michigan. “But after five years of coming to the school to train to become teachers, it is a much-sought-after program.”

For four weeks each spring, roughly 10 students from Hope work with the urban students in Watts. A few years ago, Ashley Person loved the school so much that she bugged Watts’ elementary school director until there was a teaching job open.

“She kept telling me she was coming back here to teach, she loved it so much,” Yelding said. “And now she is here.”

The school moved a few times after leaving that room in the projects and ended up in a church next to the 110 Freeway, in the landing path of LAX. This fall they’re opening a new two-story building that’s part of a $9 million construction project. In the center of the campus is a tower that projects lights over the community.

A chemistry major, Fisher had no experience in education when he started the school. But statewide focus groups showed that good schools were needed in low-income urban areas, and he wanted to help.

Fisher joined with Sandra Porter, a retired LA Unified principal, who helped run the school in the first few years. Today, she is his wife and the den mother of the school — and gets hugged by dozens of students whenever she visits.

The school adopted the abbreviation WLC, which also stands for “We Love Children,” but they had to recruit students when they first started.

“I was driving around in a big black car looking for 5-year-olds,” Fisher laughed. “I know it sounds creepy. But we were asking people to come to our school and learn math and reading, and they would be served breakfast and lunch and an after-school snack — all for free until 6 o’clock at night.”

The parents who brought their children to Watts were concerned they were not getting an adequate education at their local district school.

“We had no idea what we were doing at first, but we figured we could do it, and we did,” Fisher said. “If I knew how hard it was, I never would have started it. But if I knew it was this rewarding, I would have started it much earlier.”

- Gene Fisher and student with her mother.

- Gene Fisher greets a class.

- Teacher Alma Rubio with Sandra Fisher

- Students during lunch.

- Founders of WLC Sandra and Gene Fisher.

- Robin von der Lancken teaches at Watts.

- Kenya Edley teaches her class.

- Sandra Fisher visits a classroom.

- Teacher Michele Francis

- Ryan Porush, a documentarian is working on a story about the school.

- Mallory Johnson’s class.

- Fisher helps a student.

- Sharing space at Dymally High.

- The trophy case of the middle school.

- LA School Report’s Laura Greanias with Gene Fisher.

- Students making a presentation.

- Fisher speaks before the school board.

- Sima Aleahmad and her class.

- Fisher with John A. Yelding from Hope College.

- Watts Middle School is hoping to share the pool.

- Teacher Ana Sampson and Sandra Fisher

‘THE STUDENTS COULD LEARN’

“The Fishers came to education with a philosophy that the students could learn, and that they all have an enormous capacity for learning, even while surviving day to day. They knew that the low-income community could perform well and that high expectations really mattered,” said Jim Blew, one of the Fishers’ first advisers who later became the director of K-12 reform for the Walton Family Foundation, the nation’s largest funder of charter schools. He is now director of Student Success California, an educational advocacy organization.

Blew remembers sitting around a table with the Fishers and other board members dreaming up a new school.

“The charter school concept was still pretty new, but the group collecting around a Watts school thought it had a lot of promise for serving local students. We were surprised to learn that, of the 100 or so charters in the state at the time, fewer than 10 were located in low-income urban areas.”

He added, “Watts is distinct and home-grown. It comes from a unique vision that isn’t part of a larger network.”

Blew said the Fishers’ humbleness has played a big role. “They have a patience and tolerance that is necessary for education leadership.”

Having the autonomy of a charter school allows them freedom in choosing how to help students achieve. The philosophy of the school includes:

✦ Every child must be known, understood, and respected because children are at the center of the educational process.

✦ Parental involvement and volunteer services support and enhance the teaching and learning process.

✦ Children play an active role in the learning process.

✦ Educational experiences should enable students to communicate effectively, solve problems competently, think critically and creatively, and act responsibly.

Blew said Watts Learning Center “wrestled with various factions within the LAUSD bureaucracy,” but eventually the school proved itself and is on its way to “becoming a world-class academic institution.”

OBSTACLES

It hasn’t been easy, and Fisher is the first to acknowledge that they faced a great many obstacles getting their schools started. Former LA Unified Superintendent John Deasy didn’t want to renew their middle school charter when test scores didn’t improve. “We were co-located with another school and there was no place for kids to eat and they didn’t have a good place to go to the bathroom, and that affected the whole school,” Fisher said. When they moved, things improved.

The elementary school’s Academic Performance Index, a school achievement measure that was discontinued in 2013, rose steadily from 577 in 2000 to 852 by 2011 — far ahead of other schools in South Los Angeles, Fisher said. The API scores topped 800 for four years in a row, ranking the school 7 out of 10 in state test scores while most of the neighboring district schools ranked 1 or 2.

While Watts was above the 800-mark in the old API scores, the schools didn’t score as well under the new Common Core style of teaching and testing. Last year, Watts elementary students were slightly below the LA Unified average in English language arts, with 35 percent meeting or exceeding the state standard. In math, however, they scored 16 percentage points higher, with 44 percent of students meeting or exceeding the standard, compared to 28 percent at LA Unified.

“There was a downturn and that was a pilot year and we did not have a comparison, but we are hoping for a 10 percent increase from what we did last year,” said Kelly Baptiste, the elementary school director. The students weren’t used to taking the tests on Chromebooks, and now they are getting used to the computers.

The teachers are sometimes not ready for teaching in an urban area where children are being recruited into gangs or where parents battle substance abuse.

“We don’t expect our improvement to be a straight line,” Fisher said. “There will be jigs and jags along the way, as long as the trend is going to be upward.”

The school uses an innovative Singapore math program that focuses on teaching concepts and problem-solving skills, rather than on memorization. A board member for Yoga for Youth, Fisher wants to bring yoga to the classrooms too.

And they have seen loyalty to the school. Already there are second generations of children coming to the school, and their alumni have gone to major universities, including a recent one who is heading to USC on a football scholarship.

A ‘GOOD WORKING CHARTER SCHOOL’

Watts Learning Center’s modest improvements are being noticed. Board member Richard Vladovic has praised it as a prime example of a “good working charter school” in his district, which extends south to San Pedro. The school made improvements as they got renewed every five years by the school board, and he said this is an example of a school model that should be replicated. At one of their last renewals, Vladovic was concerned that they improve their reclassification of English learners. After seeing the school’s plan, he was satisfied.

“When I visit there, I go into the classrooms and I see that teachers are teaching and I am impressed,” Vladovic said. “They should keep doing what they’re doing.”

Board member George McKenna echoed the praise and said, “This school has been successful, and that’s something to see.”

And new board President Ref Rodriguez said, “Watching what they’ve been doing for two years that I’ve been here shows they are just getting better and better.”

The Fishers even have an independent movie crew following them around to document the uniqueness of the schools that are “set against the backdrop of a politically and socially divided nation,” filmmaker Ryan Porush said. The movie, “A School Grows in Watts,” plans to weave together the personal narratives of the students, teachers, and families involved with the “unconventional and overachieving charter school” with the “tragic history of South Los Angeles and the systematic barriers facing children in inner cities.”

Porush said, “It’s a story that should be told.”

When walking into any of the Watts Learning Center classrooms, it’s unlikely the students will be sitting at their desks. They may be on the floor in a circle like in Sima Aleahmad’s class, talking about what upset some students at recess, or taking turns presenting their work like in Kenya Edley’s class, or sitting in groups learning about the California Gold Rush, like Michele Frances’s fifth-graders.

The Watts Learning Center’s elementary school director, Kelly Baptiste, said that although the school district remains supportive of the school, her staff is inundated with forms and informational requests from LA Unified’s charter school division in order to keep their charter.

“The paperwork from the district is excessive every year,” Baptiste said. “We have to renew the petition every five years, but the paperwork is every year, and it is constant.”

Fisher said he doesn’t mind the level of oversight of the school. “When the boss tells you to do better, you go out and improve. Our scores were not what we wanted academically, and there were serious challenges posed by the district.”

The middle school started in 2009 and is co-located with two other charter schools on the campus of Dymally High in Watts. The school still has to work out some issues with the district school, as they seek to share lunch spaces, the air-conditioned library, the athletic grounds, and the swimming pool.

“The students feel low if they come to this school that is so beautiful and they are told you can’t use the pool,” said Fisher, giving a tour of the three-story middle school that they share at Dymally.

The middle school director, Gayle Windom, said there has been progress in getting a check-out system so her students can use the library, and that it took a bit of negotiating to have space for their children to eat lunch. The middle school can grow to a total of 420 students and now has about 380.

Eventually, Fisher wants to have a high school too. And they want to start education early with pre-K and transitional kindergarten classes.

“We know if their reading is not up to par by third grade, there is a 50 percent chance of them not graduating from high school,” Sandra Fisher said. “We work with the parents too, and try to get them involved in their child’s education.”

It’s not always easy to do that, and Sandra Fisher recalled that sometimes they have to remind mothers to pick up their children from school by 6 p.m. They deal with homelessness and undocumented issues as well.

‘WHAT WE STAND FOR: PERSEVERANCE’

The Fishers team up with companies to take the children out of Watts when they can. An annual trip gets them to Lake Hughes for a few days, and they have taken students to Senegal, South Africa, Togo, Egypt, and Brazil.

As she greeted students around the school, Sandra Fisher was still limping slightly from breaking her foot during a trip to the Amazon rainforest, chaperoning students to show them life in other parts of the world.

“I wouldn’t let it bother me, but when we got back they told me I had a fractured fibula,” Sandra Fisher said. “It just shows what we stand for: perseverance. That is the key to what makes us sustainable.”

Gene Fisher said, “We have been here for 20 years and nothing has stopped us.”

His wife added, “And believe me, we have had everything thrown at us.”

Despite police sirens blaring and helicopters buzzing overhead, the Fishers and their team continue to work to make their students feel safe at the Watts Learning Center.

Fisher sighed as he described the crime that still marks the neighborhood. But, he said, “I just tell the children, most people who join gangs are not intelligent people.”

*This article has been updated to add school demographics.