Q&A: Harvard ruling will put spotlight on college elitism, Georgetown economist says

Kevin Mahnken | July 13, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

What now?

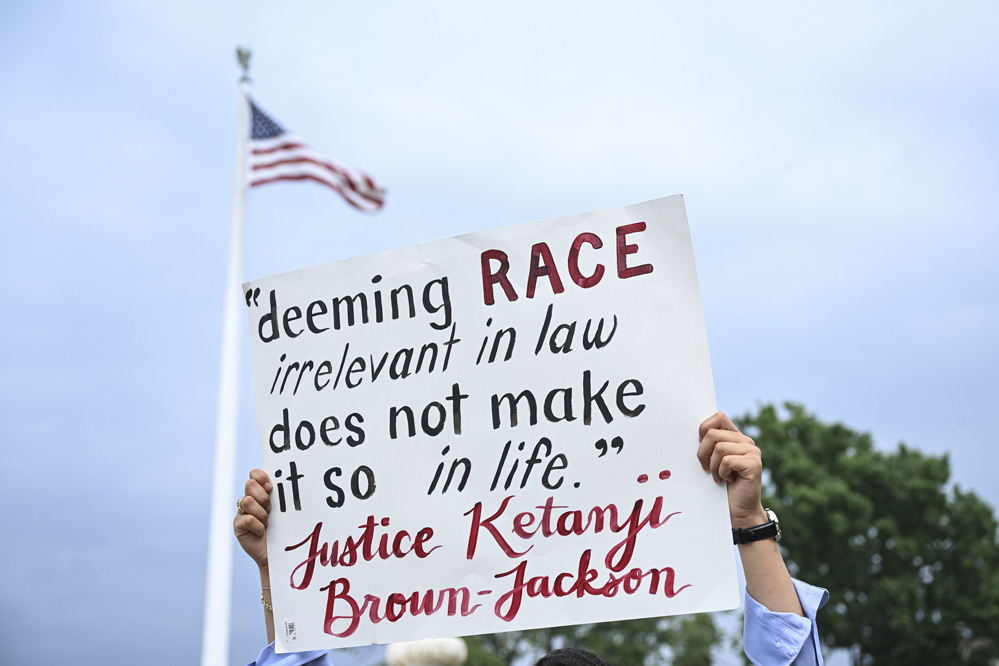

That’s the question confronting university administrators, faculty, applicants and their families in the wake of the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College. The 6-3 ruling by the Court’s conservative majority struck down race-conscious admissions policies at both Harvard and the University of North Carolina, overturning the decades-old model of affirmative action in higher education.

That system — blessed by an earlier version of the Court in the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case — allowed schools to include race as a consideration in offering university acceptance, but only as a means of cultivating the benefits of a diverse student body. But after a series of failed legal challenges over the past 20 years appealing to the bench’s increasingly rightward tilt, a group of Asian plaintiffs prevailed in arguing that they were unconstitutionally disadvantaged by affirmative action as currently practiced.

“Many universities have for too long wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the color of their skin. This Nation’s constitutional history does not tolerate that choice,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority opinion.

But if the status quo of college admissions has been cast aside, a replacement hasn’t yet been offered. According to Georgetown University’s Anthony Carnevale, the future remains murky.

Carnevale is the longtime director of Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW) and one of America’s most-cited economists on the intersection of schools and the labor market. A former member of multiple federal panels on employment and technology, and a passionate advocate for additional K–12 funding and policy experimentation, he has long pondered the question of what might follow an abrupt end to affirmative action.

His observations and proposals fill a 134-page CEW report published in June, which may help shape colleges’ and policymakers’ response to a new landscape of socioeconomic mobility. If elite schools can no longer act as an access point for historically disadvantaged groups to enter the middle and upper classes, he and his co-authors argue, the logic of broad-based education reform — including both dramatically boosted resources and an overhauled approach to college and career counseling — becomes inescapable.

In an interview with Kevin Mahnken, Carnevale discussed the legacy of the Bakke case and multiple generations of racial preferences; the plausibility of class-based selection metrics replacing the vanished system; and the future of a higher education sector that could increasingly come to be seen as elitist. While lamenting the end of affirmative action as we knew it, he argues that colleges should step up efforts to become truly egalitarian.

“One of the problems for elite colleges is that they’re going to become unpopular because everyone is going to see them as what they are: institutions that preserve elites,” he said. “If you’re an elite college president, that’s a problem you have to deal with.”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What’s your perspective on this ruling and the legacy of race-conscious admissions?

Basically, affirmative action has been a Band-Aid that’s been used by politicians and the rest of us, so that we have a little racial access to elite colleges. And it’s stopped us from truly reforming education. Now the Band-Aid has been ripped off, and race is a gushing wound in America.

In the end, what disgusts me most about this outcome is that they’re demanding that minority applicants humiliate themselves. The best way for a minority to get into Harvard now — it’s allowed in this opinion — is to write an essay about the hardship you’ve suffered; that your parents abused you, that your neighborhood abused you, that you got beaten up going to school every day, and that was good for your character. I find that humiliating, to turn on everyone you know and care about so that you can get into Harvard. Telling your story in this way is kind of like racial porn: “Let’s see who’s got the sorriest story to tell, and we’ll let them in!”

There are definitely going to be fewer African American, Latino, and Native American people on campus, no doubt about it. That’s what’s going to happen here. The question is, how does everybody respond?

How do you think they’ll respond? Are college admissions officers freaking out right now?

Anthony Carnevale: I’m not sure about “freaking out.” I go to meetings of college officials where this topic is the center of the discussion, and people basically don’t know what they’re going to do. In one of those meetings, a lawyer opened the conversation by saying, “The first question you have to answer is, do you want to get sued?” I thought, “Boy, that’s a good question.”

If you want to make your name in higher education, you can disobey this ruling and let them sue you. If you’re Harvard or Georgetown, and slaves helped build the buildings, maybe you should do that and make a point. But I don’t see any way out of this because the anti-preferences side is committed, and not all of them are racists — a lot of them are just idealists. They’re well-funded, they’re well-organized and they’re always three steps ahead. They’re already challenging changes to Gifted and Talented programs, and if anyone’s wondering whether they’ll persist [in those challenges], I think the answer is yes.

If I were as rich as Harvard, I might simply disobey the ruling. What are they going to do? They’re like the pope — they have no army. Maybe they’ll sue you.

Deliberately contravening a Supreme Court order seems incredibly risky, though. I wonder if universities are entering a particularly dangerous period with respect to the law and public opinion.

It is risky because people’s feelings are easily aroused on this issue. One of the things that will happen is that the ACE [the American Council on Education, a nonprofit advocacy group representing 1,700 institutions of higher education] will take a beating.

I think the College Transparency Act [legislation re-introduced this spring, which aims to modernize data collection from universities and give families a fuller picture of schools’ enrollment, completion, and post-completion earnings statistics] will pass when there’s an opening for it. It has strong, bipartisan support, and one of the things you can do to whack higher education is to make them more transparent in terms of their employment and earnings effects. There’s also a push for expanding funding for workforce training, so we’re going to get transparency on degrees and accountability on training. All of that stuff will move now.

I worked on the Hill a long time, and higher education annoys politicians because they think it’s arrogant and ungrateful. Higher education leadership tried to stop the GI Bill, and they lost. They tried to stop student aid because they wanted that money to go to institutions, and they lost again. They lose at every turn when it comes to issues going beyond higher education. Whacking the elites is a common American sport that appeals to both parties for different reasons.

So if I’m a lobbyist for higher education, I’m looking for another job.

What has been the final legacy of race-conscious standards of college admission since the Bakke case?

The importance of Bakke was that it saved race-conscious affirmative action just in time. There were questions even then about whether it could survive, and it’s never been popular.

If you ask the American public straight-up, “Do you agree that we should give racial preferences in admissions to selective colleges,” a majority will say no — and that includes a majority of African Americans, Latinos, etc. If you ask them, “Do you think there are fundamental problems in the American system that are racist and need attention,” they’ll say yes. But if you give them anything specific, they’ll reject it.

So Bakke saved the day by deferring to the expertise of educators, the notion being that educators understood higher education better than judges do. What has now happened is that the deference is over, and they’re no longer going to defer to American education institutions on race. The argument is that race is too much; even if diversity is a good thing, we can’t base admissions decisions on it because that would be racist.

Could there be any replacement measures for racial preferences?

The courts have been chipping away at preferences in admissions for a long time, and we’re now at the point where they’re saying it’s the end. But it’s not clear that it is. In many people’s judgment — lawyers and others — courts will begin to defer to class instead. Many decent people argue that the real issue of concern here, across all our diverse peoples, is class. We believe strongly in striving and Horatio Alger, and we want to reward that. The polls make clear that the public still believes that, and it’s part of our culture.

The classic story is Poor Kid Makes Good. Everybody likes that, you want to give that kid a break. But for some reason, we don’t recognize the connection of race to American history and the disadvantages that are still there. It’s a failure to deal with American racism, and it has been since Bakke. The hope among some people is that we’ll use class as a proxy for race, but class and race are not the same thing. They are two very different forces in disadvantaging people’s lives, though a lot of people notice that they often go together.

We’ve done a very long set of studies over the years and discovered that, no, you don’t also get race when you screen for class. You can claw back a bit of the racial diversity you had before affirmative action was banned, but not much of it.

Nevertheless, a lot of people are celebrating a potential switch to class-based affirmative action, saying, “Finally, going to Harvard isn’t just going to be for rich minority kids anymore.” The truth is, it never was. Most of the African Americans and Latinos who go to the top 193 schools are from the bottom half of the income distribution. A lot of them aren’t poor in the classic sense, but they’re not a bunch of rich kids.

The thing people don’t talk about when it comes to class-based admissions is this: A basic problem for people who are poor is, obviously, that they don’t have money. And with the exception of places that are filthy rich, like Harvard and Yale — they can do whatever they want, and their concern is prestige rather than money — colleges just can’t afford class-conscious affirmative action. There have been efforts, but what people forget about colleges, whether they’re selective or not, is that they’re businesses. What they’re always trying to do is find as many kids who can pay full tuition as possible, and if they’re lucky, more than 50 percent of your families will do that.

There’s a bargaining process that every middle-class family is familiar with, where families visit eight colleges and strike the best bargain they can within their kids’ preferences. The colleges will give them “merit aid,” but what it is is a bargain. You get all the full-pay parents you can get, and you haggle with the parents you have to haggle with. Then, whatever you’ve got left over, you can use it for athletes, legacies, the trombone player you need in the band. But you really don’t have room for many poor kids.

You might say to these schools, “You’ve got an endowment of something like $2 billion. How the hell can you not afford it?” Well, if a college president takes money out of the endowment, the alumni are going to get him fired.

How did this whole focus on diversity get started?

As a practical matter, this has always been about white kids. James Conant, who was the president of Harvard after World War II, determined that we needed 5 percent of kids to go to college. He therefore decided that we should build a certain kind of high school nationwide, the “comprehensive” high school. It was comprehensive because it offered a college pathway to a small share of the kids; it offered vocational education, mostly for boys; and it offered home economics and typing for women.

But one of the big moments in the history of education came in 1983. After A Nation at Risk, we decided to do away with the comprehensive high school and provide every American child a full academic education through high school. And the real political reason behind that reform was the civil rights movement, the women’s liberation movement, the disability movement. Basically, anti-tracking sentiment killed the comprehensive high school and, in the end, created an academic curriculum that assumed everyone would go to college. Since Obama, the battle cry has been to make every kid college- and career-ready, but of course, high schools don’t. A lot more kids are graduating high school and going to college, a lot of them are dropping out, and a lot of the kids who don’t make it are the ones you’d figure wouldn’t make it.

Underneath all this, there’s a fundamental shift in the relationship between education and the economy. We needed an elite to run our military, our businesses, every institution in American life, and most of these people were going to be white males. We realized that if you’re going to run a diverse economy and be the global leader in a diverse world, you need to have some understanding of demographic diversity. The reason we did affirmative action was for them — they needed it! If you’re going to run a company in America, you need to have a diverse workforce, or Reverend Al’s going to show up.

The way this will work out is that employers will need to have diversity in their leadership. They’ve got to “look like America,” as Bill Clinton used to say. So irrespective of what the court’s done, they’ll go to UMass instead of Harvard to recruit, and they’ll find plenty of talented minorities there. They’re serious about this, and they have no choice — you can’t run a company with an all-white leadership team.

What about the political consequences?

It will be hell for the Democratic Party. The Supreme Court has effectively put a Band-Aid on racism for years, and now we’re ripping it off. If minorities are a core part of your coalition, you’ve got to come up with something for them.

Joe Biden’s answer is: We’re going to go back and do what we should have done in the first place. We’re going to have preschool for everyone, we’re going to increase spending for Title I, we’re going to increase funding for low-income schools, and we’re going to make community college free. In other words, now that you can’t just mess around with the elite schools, you’ve got to focus on the whole damn system. That’s not very satisfying because you’re talking about 40 years of work. There’s going to be much more focus on making the education system produce minority elites who aren’t from rich families.

The landmark case was brought by Asian American plaintiffs who argued that Harvard’s admissions policies discriminated against them. (Getty Images)

This changes the conversation on education reform, which has run out of gas at the K–12 level. That discussion is about to get revived because there’s nothing else to do except go back to the beginning and get it right.

That sounds refreshing, but also potentially impossible.

In the end, K–12 has caused this problem, so we’ve got to go back to court cases in the states. There have been a lot of those, and they’ve been reasonably successful over the last few decades. But it’s a big, big deal. Politically, it’s going to be awful because what you’re talking about, in part, is screwing around with the local control of schools.

The education system is now the primary pathway to a good job in America. That wasn’t true back when I was young. If you had an uncle working at Chrysler, he could get you in.

You didn’t need to go to college; truthfully, you should drop out of high school instead of waiting. But in all the research — OECD [the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] was the first organization to start saying this, in the ’90s — the education system is now the primary institution that ensures the reproduction of advantage from one generation to the next. It’s a machine where you go to a good grade school, a good high school, a good college, and you get work-based learning and internships. Then you marry a college graduate, move to a neighborhood with good schools and the whole thing starts right over again.

The thing is, it’s hard to argue with. And if we weren’t a diverse nation, it would be an ideal system. But we are a diverse nation, and diversity clearly matters in terms of who wins. Both Republicans and Democrats have tried to reform the K–12 system, and they did good things, but it wasn’t nearly enough.

What I’m hearing is that this change to college admissions is occurring in an economy with an increasingly ossified relationship between higher education and success in life.

The endgame now is much clearer than it used to be. According to our projections, which run out to 2031, we’re going to have 171 million jobs. Forty percent will require a B.A. or more, and about three-quarters of those jobs will be good jobs. Meanwhile, 30 percent of all jobs will be middle-skilled, and maybe 40 percent of those jobs will be high-paying and secure. And then there’ll be jobs for high schoolers, only about 20 percent of which will be good jobs — largely because of the infrastructure bill.

That said, there’s still quite a bit of variability. That’s why, in the United States, 40 percent of people with B.A.s make more than people with graduate degrees, and 30 percent of people with A.A.s make more than people with B.A.s. It’s a system, more and more, where what you study really matters. If you go to a community college and learn about HVAC, you’re going to get a good job. There’s movement here.

Why wasn’t affirmative action ever popular? You mentioned the fact that polling around it is terrible, but it was also striking that a ballot measure to bring back race-conscious admissions failed — in California, of all places — a few years back.

Think about it: Every family has that guy — in my family, it’s a couple of immigrants — who came over and worked hard with a pick and shovel, and by the third generation, we all went to college. Everybody’s got that story about themselves and their families, and we’re almost neurotically tied to hard work and individual success. The idea that somebody who worked less hard or was less qualified could get the job over my grandfather, which they did, was anathema. The striving, the upward mobility, is what we reward.

Now, if you recognize racism in America, you ought to question that perspective somewhat. That is, in America, there were people who weren’t allowed to strive. But it’s a tough American problem because it creates the cultural contradiction of rewarding people based on the color of their skin. You put that to the average guy in a bar, he’ll say, “Hell no! Whoever works the hardest and does his homework should get the job.” To my mind, it’s a very superficial understanding of the United States and its history, but we are who we are.

If I’m a Republican, I’m standing up to make a righteous speech about how the people who deserve advantages are now going to get them. Even if you look at Democrats, they tend to agree with that, so you’ve got to find a Plan B. I’ve worked for a lot of politicians, and boy were they happy that the Supreme Court handled abortion and affirmative action. Now it’s falling into their laps.

If you’re a Democrat, the abortion ruling last year was very advantageous. On affirmative action, not so great.

Is it possible that colleges will effectively ignore this ruling? They can just jettison the use of admissions exams, which were a big part of the evidence in this case, and admit whomever they like, right?

If you look at the data, test-optional [admissions] has increased the recruitment of high-income kids. White kids. If you take the test away, colleges and universities can admit more legacies, the quantity of whom is growing all the time. After this decision, they can admit anyone — except African Americans and Latinos.

In an ideal world, if you’re talking to a student who wants to go to your college, you should be talking about the whole kid, not just their grades. There’s something to holistic admissions. But it also frees up colleges to do whatever they want, and what they want is not to admit poor kids. The flip side is that in American politics, elitism is not a good look. Americans don’t like elites, even if they themselves are elites. There are already bills in Congress that would prevent colleges from admitting legacies. That won’t go anywhere, but we’ll get transparency on legacies; they’re going to have to report to the Department of Education how many legacies and donor kids are in their freshman classes. You can call it grievance, or revenge politics, but it’s going to happen.

Harvard grad student Viet Nguyen started a grassroots organization determined to end the practice of legacy admissions at colleges. (Getty Images)

One of the problems for elite colleges is that they’re going to become unpopular because everyone is going to see them as what they are: institutions that preserve elites. If you’re an elite college president, that’s a problem you have to deal with. If you don’t have any African American or Latino students on campus, people aren’t going to like it. Resentment politics might become stronger in higher education because the class differences and race differences will get even more real.

Class has always been real — elite colleges have always done better with race than with class. If you walk around on a college campus, you can’t tell what a poor kid looks like. But you’ve got a much better chance of bumping into an African American or Latino kid than a poor kid on an elite college campus. They just don’t go there.

Combined with the decision to overturn the Biden administration’s student debt forgiveness program, we’ve now seen big reversals for universities as engines of social and racial equality. It seems like higher education will increasingly come under some skepticism from the political realm.

Yeah. We’re going to get a big emphasis on training and career education because it’s a program that can reach the working class in a way that Harvard and a lot of four-year schools never could. The Democrats need it to shore up their working-class voters, and the Republicans need it to retain white working-class voters as well.

So higher education is going to get some competition from training. That’s good for two-year institutions, but not four-year institutions. More than 20 states now allow you to get bachelor’s degrees at community colleges. Higher education is being rebuilt, in other words. Pretty soon we’ll have a mandate to force higher education institutions to tell their applicants what happened to all the other students who took the program they’re in, whether they got a job, and how much money they made. The data is there for that.

Transparency and accountability is about to come to higher education. You can’t stop it now.

Is it possible this judgment will affect a school like Harvard much more than one like UNC? My guess would be that the types of students who are currently benefiting from racial preferences at the most selective institutions will just apply, and gain acceptance to, slightly less selective institutions. But the more elite the institution, the more challenging it could be to find top nonwhite students.

Yeah, it’s not a choice for these kids between Yale and jail. It’s a choice between Yale and Dartmouth, or Colby, or Bates. But it should change the demographics at the top, say, 40 institutions, and people will be pissed off about it. The newspapers will write headlines about the shrinking number of minorities enrolled at their local colleges, and that will get noticed politically. The decline in the number and shares of minorities at elite colleges will be a constant topic. The people who fund me already want me to get in and start tracking this.

Did affirmative action save America from racism? No, that’s pretty clear. But it allowed elites to operate in a way that made them seem like they were progressive and honoring America’s racial history. So the reputational effects are real. Parents are going to want their kids to go to diverse schools, and there might not be many.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.