Q&A: Rocketship Schools’ co-founder reflects on 15 years of empowering parents and the growth of 13 campuses across California

Richard Whitmire | April 6, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

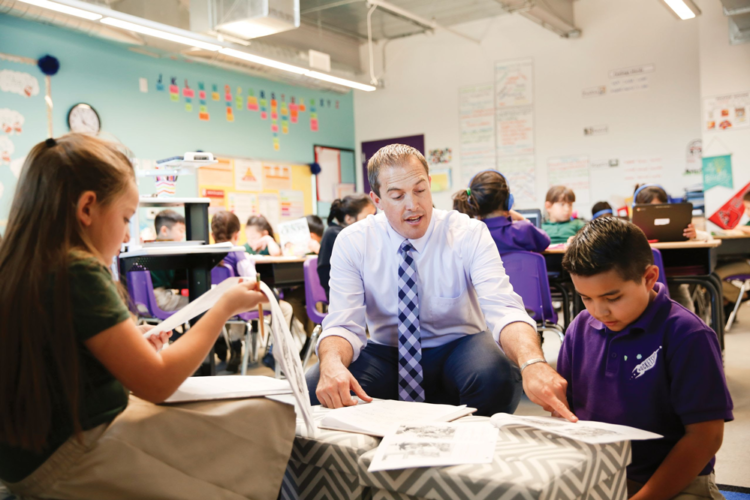

Preston Smith (Rocketship Public Schools)

In the fall of 2011, having hurriedly finished The Bee Eater, a book about Michelle Rhee’s tumultuous turn at the helm of D.C. Public Schools (hurriedly because Rhee got the ax when her protector-mayor got voted out of office) I was looking for a really, really fresh approach to public education, especially schools that serve poor kids.

If a fierce reformer such as Rhee couldn’t survive in a troubled urban district, then maybe charter schools were the answer. But which charter network to pick to profile?

I had never heard of tiny San Jose-based Rocketship charters, but several savvy charter school followers pointed in their direction. I flew out to San Jose, met with co-founders John Danner and Preston Smith, and they agreed to provide me complete access to their schools and expansion plans over the next year. Over the course of that year, I earned a lot of airline miles flying back and forth to California, and even more miles as they expanded to Milwaukee and Nashville. The result, On the Rocketship, was published in 2014. I then departed for other book projects.

Today, Rocketship Public Schools has turned 15 – celebrating its quinceañera, as long-time Rocketship leader Maricela Guerrero aptly put it, considering the network’s roots in educating low-income Latino students – with about 10,000 “Rocketeers” across the country, with 13 schools in California, two in Milwaukee, three in Nashville, three in Washington, D.C. and one in Fort Worth, Texas. Over its 15-year history, Rocketship has served 27,508 students.

This seemed like a good time to catch up with Smith, who today shares the title of co-founder and CEO. Back then, Smith and I spent many hours together on school tours and sitting across from one another with a digital recorder, so for me, this was a reunion of sorts.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

While I was researching the book you told me so many great stories about the early startup years, when you operated out of a tiny, unairconditioned space at St. Paul’s Methodist Church in San Jose. One of my favorites was about you having to move 40 traffic cones every morning and then move them again in the afternoon, to accommodate the parishioners. Your exact words during our interview when recalling those years: “I’ll never move a damn cone again for the rest of my life.” Do you have any better stories about that time?

You know, Richard, that is a great one. I’ll stick with that one. But once in a while, to help our school leaders during startup, I help out with moving cones. So, time heals all wounds.

Let me give you another story. In our church space we had different learning centers, a center with blocks, a center with enrichment, etc. There were all sorts of materials, carpets, tables. Every Friday the church group held a dance, so every Friday afternoon we had to clear out that space, moving everything. So it was like a huge fire drill. And then every Monday morning, we had to set it up again for the kids.

In some ways, Rocketship is a typical charter network, with an emphasis on academics and college readiness. But in other ways, you are very different, creating only elementary schools, putting parent empowerment as a top priority and keeping an eye on the biggest prize: social change around education.

Let’s first discuss your K-5 model. The biggest charter networks have gone to K-12 models, mostly on the assumption that to make their students truly college-ready they can’t send them off to traditional schools where academic gains might be lost. Why doesn’t Rocketship do that?

First is that it is unlikely that we, or anyone, can scale to the size of the challenge within public education, so we have to be innovative in how we think about sharing our model and impact with other kids, families and schools beyond directly enrolling more students. We do not want to be a parallel K-12 system, rarely interacting with other school systems. Rocketship does not believe that contributes to a larger ecosystem of impact.

Rather, by being K-5 it creates much larger catalytic effects for our kids, families and communities in regards to high-quality choices, district or charter. We believe that by creating a bunch of K-12 systems we would actually be undermining choice, which is a value we as a movement say that we value. That would encourage families to make the choice to opt into one K-12 network and then not make any further choices. Thus, the K-12 approach ironically undermines our value as a movement of choice.

Your theory of change has always been that Rocketship will take in low-income students, deliver a superior education, empower their parents and then send them to schools that will have to adapt to these students and their parents, who will demand better educations. And yet, at least in the early years, the traditional schools, especially the teachers unions, have fought you at every turn. Have traditional districts started to make changes as a result of your schools being in their district?

We’ve definitely seen it in each of our regions. What I’ve learned over time is this power of being only elementary, right? It starts with a great education, and then you couple that with parents who become super powerful through advocacy. From their years with children at Rocketship, they understand how to navigate and influence the system. They not only understand what a high-quality school is and what their Rocketeers deserve, but they also know how to navigate the political and leadership system and community. And that creates systemic change, community change. We’ve seen it in San Jose and every place we’re at.

Could you cite some examples?

Sure. Here in San Jose, where we have 10 schools, our kids are showing up in middle school a year ahead in academics, and those gaps actually grow in the subsequent years. They are going to be in really strong shape no matter what kind of school they choose. Several middle and high school charter schools have grown up here in San Jose and even the local traditional districts have innovated, opening up schools of choice, small autonomous schools, dual immersion schools [where English- and Spanish-speaking students learn together in both languages]. And if you look at the overall results of the surrounding districts, everyone is doing better. So I really think that has proven our theory of change.

In Milwaukee, where we now have two schools, what we saw is the district really wanted our Rocketeers, so they opened additional middle schools so they could serve our kids. Also, we used to partner with community organizing groups, but in 2015 we shifted, based on this theory of change, and made organizing part of who we are at Rocketship. Now, we have Rocketship employees who are education organizers who work with the families not just in our schools but with other district and charter schools to organize families to access power. That helps us drive this theory of change in a larger sort of community and ecosystem.

Most charter networks were launched with an end-goal of college readiness, which in more recent years expanded to college success – ensuring that students not only enroll in college but actually earn degrees, hopefully in four years. Now, suddenly, and partly as a response to the pandemic, an anti-college movement is afoot as seen in the rapidly declining enrollments. The belief that a college degree is necessary in life has begun to fade. Has that affected Rocketship?

I guess I’ll speak for our Rocketship community, that’s what I’m most familiar with, right? What we’ve seen is our parents are still all over college. They’re still very much motivated by that vision for their children. So, we do annual college visits in our schools, with the families. We’ve still got cohort names and college banners in our classrooms. This emphasis on getting a college education is something parents say is what really motivates them and what they appreciate about Rocketship.

That college focus is interesting for us because we have to wait, right? Our kids leave after fifth grade. And it’s years before that student gets to college. Now, we have our third class of college graduates, and we have Rocketeers who have graduated who come back to visit our schools. That has been super motivating to our families, to our team. So I’ll just say within our Rocketship community, college is what our families are still aspiring towards.

I’d like to ask the college question more broadly. Education is infamous for its ill-advised pendulum swings. Remember “whole language,” which got its start in California, swept the country and triggered years of reading instruction malpractice? Considering how fast the pendulum is swinging on college, is this another trend going too far?

I would say I deeply believe that in the United States of America we need a public education system that regardless of zip code, enables kids to have the opportunity to go to college. And if they choose not to do that, that’s fine. Right? That is their choice. But I am still deeply motivated and deeply inspired by a country that believes in public education. You should be able to attend a free school that’s high quality and gives you the opportunity to go to college.

My question here is whether this [anti-college movement] is more a reflection of the reality of how our current public system doesn’t provide that quality education to prepare students for college. If so, we still have work to do.

A few charter networks have figured out ways to enroll better prepared students from more motivated families. In short, gaming the pool of low-income families. Not surprisingly, their academic outcome data consistently looks outstanding when compared to their close-by neighborhood schools. I spent enough time in Rocketship schools to know that doesn’t happen there. If anything, you lean in the opposite direction. And yet, that gaming has to be tempting, right? Great headlines when the test scores come out.

No!

Our challenge is serving kids in socioeconomically disadvantaged zip codes, often Black and Latino kids, right? For me, that’s the challenge, giving all those kids in those zip codes a chance to go to college. That’s what we’re obsessed with at Rocketship. The more we get into learning how to do that, the more we have to share with other schools to influence the larger system, right?

We’re not interested in designing magnet schools [that attract the strongest students]. There’s a place for them in the United States, sure. But the massive need is designing true public schools that serve all kids.

In San Jose, Rocketship clearly showed that it could succeed with low-income Latino students in ways the local traditional public schools could not. You pretty much wrote the book on that, and you could have stuck with that student population, nationally. But you didn’t. That sense of mission led you to expand into cities such as Nashville and Washington, D.C., where you started to serve mostly Black students. A lot of people (OK, maybe me as well, considering my D.C. reporting for the Rhee book) thought you would stumble at that abrupt transition. I know it was rocky, but based on school outcome data in those cities, you appear to be succeeding now. Please talk about that.

Now, I feel so blessed and grateful for the opportunity to open schools that are so disparate. Opening in D.C. meant opening in a very different community, where a third of our students were homeless in our second year. We had never seen anything like this. The amount of trauma, and the counseling that was needed was new for us.

Think about that. Our school was the largest charter that ever opened in D.C. Our authorizers were skeptical. That was hard. We were learning how to do this. What do we do? How do we raise the bar, push the bar, for kids like we’ve never seen before? The beauty of that was reconsidering our Rocketship model. Oh, we need counselors. We need counselors who understand trauma. We need to better discern the scaffolding of our behavior management to get smarter, better and faster.

And now, that’s all in our model, and not just in D.C., right? You fast forward to San Jose, and now we have mental health professionals in every school. Everybody should do that. We learned that. So that has benefited all kids, not just in D.C. If we had just remained in San Jose, I don’t think our model would be as rich as it is now. Being in Milwaukee, Texas, D.C., Nashville, we’re seeing very different communities, very different needs, very different learning styles. That’s how we have elevated our overall model.

Here’s the other thing. We got launched in San Jose with English language learner models we developed. And then you go into districts such as D.C., where people tell us those teaching techniques aren’t needed, because these students aren’t learning English. And meanwhile, we know that English is a hard language to learn, right? It’s not a natural language. At a young age, everyone is learning English. That skill, teaching English, and that model of teaching it, was a super powerful thing to bring to D.C. At the root of this is Rocketship as a learning organization. Always innovating, reflecting, always pushing ourselves.

For most of your startup years with Rocketship, there’s been a rocky and adversarial relationship between charters and traditional districts, especially with the teachers unions. Now, post-pandemic we see steep enrollment declines in all schools, especially the district schools. In some parts of the country, that has intensified the animosity, with traditional districts arguing they can’t afford to lose students to charters. From your perspective, how has the pandemic changed the relationship between charters and traditional schools?

There were definitely years when charters and districts were not all in this together. During the lockdowns, however, we all started sharing our resources. Overall, now there’s a shared sense of just how intense this work is trying to deal with learning setbacks. I would say at least among educators, there’s more collaboration between charters and districts, after what we all went through.

It strikes me that there’s one Rocketship practice that should be at the top of the list to share with other schools, both traditional and charter, and that’s parent involvement. You were able to do that with Latino parents, who traditionally have shied away from dealing with the education establishment. How did you do that?

It starts with making sure they’re truly treated like their child’s first teachers, making them true partners. That’s why we continue to do home visits with our families. Also, we make sure they share power, such as asking them to name new schools and help select the staff. When we hold meetings in the evening we offer food and day care to make it more accessible to our parents. Once parents are engaged with the school they are more likely to become education advocates, community organizers. That’s why we brought our community organizing in-house.

Let me give you an example. During the pandemic we established Care Corps, which placed a Care Corps coordinator in each school to help parents find the help they needed. That help included partnering with Second Harvest to deal with food scarcity, distributing boxes of produce, eggs, milk and chicken to our families.The coordinators help parents navigate support systems and get the assistance they need by overcoming language barriers, red tape and lack of internet access to connect them to vital services that are too often cumbersome and complicated.

For us, having a broader impact doesn’t always mean enrolling more students. It involves trying to share practices such as Care Corps with other districts.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.