Slowdown in health care expenses is saving school districts billions

Chad Aldeman | March 27, 2024

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Thirteen years ago this month, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA), otherwise known as Obamacare.

In theory, the ACA shouldn’t have affected public school districts all that much. Most already offered health care plans that met the ACA’s requirements to at least cover 10 “essential benefits,” and a “Cadillac Tax” on high-cost plans that had been included in the original bill was delayed and then eventually repealed.

Teachers were and remain more likely than other workers to have access to health care benefits. They also are more likely than private-sector professionals to receive ancillary benefits, like coverage for dental, vision and prescription drugs, and continued benefits after retirement.

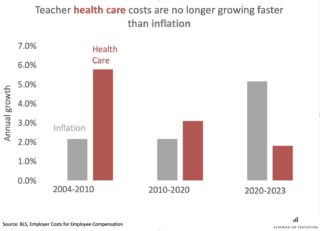

But at the time ACA passed, school district health care costs were growing rapidly. According to a survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics called the Employer Costs for Employee Compensation, the price tag for teacher health insurance benefits was rising at a rate of nearly 6% per year. In contrast, inflation was growing at just over 2% a year.

Observing these patterns in the broader economy, ACA champions talked about “bending the cost curve” and reducing the rate at which health care expenses would grow over time.

It worked. Within public education, district health care costs immediately began to slow. And, in the last three years, the relationship has flipped entirely, with teacher health care costs growing considerably more slowly than inflation.

It’s not just happening in education. Private-sector employers are seeing similar improvements, as are other government-provided health programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid.

One explanation for the slower rates of growth for employers might be that they have simply shifted more of the costs onto the backs of employees. Within education, for example, the share of medical care premiums for a typical individual health care plan picked up by employers has fallen from 89% in 2010 to 85% in 2023. The comparable rate for family plans has also dipped, from 69 to 65%.

In other words, school districts are asking teachers to pick up a slightly higher share of their health care benefits. By my rough calculations, that has cut the average educator’s take-home pay by a little more than $300 per year for those covered by individual plans and almost $900 for those using family plans.

It’s also possible that the plans themselves have changed and shifted more costs onto workers through higher deductibles and co-pays and other out-of-pocket expenses. That’s hard to prove for teachers specifically, but per-person out-of-pocket expenses nationally have risen by about $175 since 2010, in real terms.

That’s not nothing. But it pales in comparison to the savings on the employer side. According to the bureau’s data mentioned above, districts are saving a little over 9% of each teacher’s salary thanks to the slowdown in health care costs post-ACA. That works out to an average saving of more than $6,000 per teacher, or roughly $25 billion nationwide.

Of course, districts haven’t passed all those health care savings on to teachers, at least partly because districts have chosen to stretch their budgets over more employees.

Moreover, while districts may have seen their health care costs slow down, employee benefit costs overall continue to rise, thanks to large increases on the retirement side. As I noted in a piece for Bellwether last summer, teacher pension costs are rising about 8% every year, and they have shown no signs of slowing down.

In other words, district budget officials have gotten a measure of relief from the slowdown in health care expenses. But the average school employee may not be seeing or enjoying the benefits of these trends.