Steep drop in student history scores leaves officials ‘very, very concerned’

Kevin Mahnken | May 3, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

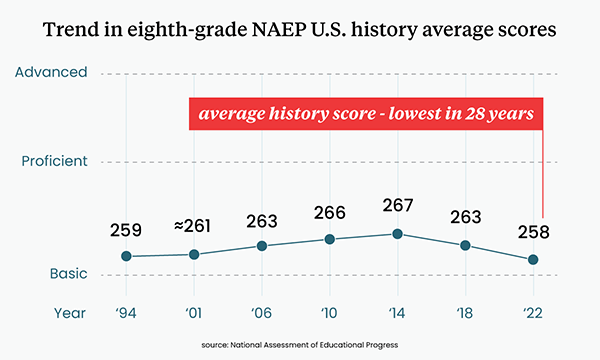

Eighth graders’ knowledge of both history and civics fell significantly between 2018 and 2022, according to the latest scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Federal officials called the decline an ominous sign for America’s civic culture, with U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona criticizing some states for “banning history books and censoring educators.”

Posted this morning, results from last year’s administration of the nationally representative test — sometimes referred to as the “Nation’s Report Card” — showed history scores dropping by an average of five points on a 500-point scale. Average civics scores fell by two points on a 300-point scale, the first-ever decline in the 25-year history of the test. After modest increases over the last few decades, performance in both subjects has fallen back to levels measured in the 1990s, when the subjects were first tested.

Taken together, the scores provide only the latest evidence of declining U.S. academic performance across a range of disciplines. Just last fall, the release of math and English scores showed severe damage inflicted during the pandemic, with years’ worth of academic growth similarly erased or massively reduced.

Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, told reporters that the unprecedented reversal in civics was “alarming,” though not of the same magnitude as last year’s release. More disquieting were the history results, she added, which began their slide nearly a decade ago and are now nine points lower than in the 2014 iteration of NAEP.

“For U.S. history, I was very, very concerned,” Carr said. “It’s a decline that started in 2014, long before we even thought about COVID. This is a decline that’s been [going] down for a while.”

Beyond the headline figures, the test also measured lower performance across all four of the sub-themes included on the NAEP U.S. history test, including changes in American democracy (minus-five points), interactions of peoples and cultures (minus-five), economic and technological development (minus-five), and America’s evolving role in the world (minus-three).

Equally noteworthy, Carr observed, was a phenomenon that has been consistent across multiple rounds of NAEP stretching back over the better part of a decade: Scores for the most successful test takers (those at 90th percentile in U.S. history and both the 75th and 90th percentile in civics) are statistically unchanged since 2018, while relatively lower-performing students did significantly worse.

Those diverging trends were reflected in the numbers of participants scoring at NAEP’s different achievement thresholds. The percentage of eighth graders scoring below NAEP’s lowest benchmark of “basic” in U.S. history (defined as only partial mastery of the requisite skills and knowledge in a given subject) grew from 29 percent in 2014 to an incredible 40 percent in 2022. In civics, the proportion of students scoring below the basic level rose to 31 percent from 27 percent in 2018.

By contrast, just 13 percent of test takers managed to score at or above NAEP’s “proficient” benchmark in U.S. history (defined as being able to read, interpret, and draw conclusions from primary and secondary sources) — the lowest proportion of eighth-grade students reaching that level out of any subject tested by NAEP. Only about one-fifth of students met or exceeded the proficient level in civics, the second-lowest proportion for any subject.

Patrick Kelly, a 12th-grade teacher of AP U.S. government in suburban Columbia, South Carolina, said that the results, while disappointing, could hardly be called a surprise. In spite of their importance to the country’s social fabric, he continued, requisite attention and precedence has not been granted to either history or civics.

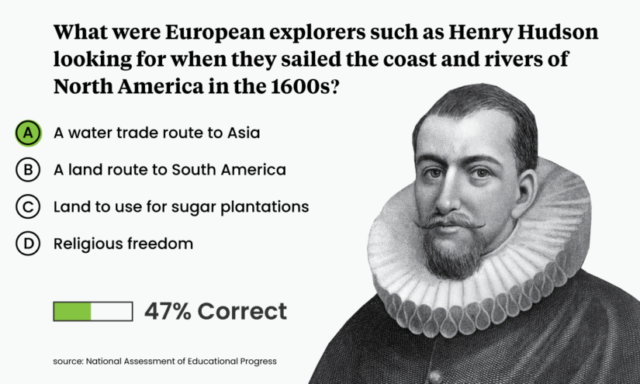

Sample question (NAEP/The 74)

“When it comes to social studies instruction, we’ve marginalized it for quite a while nationally,” said Kelly, who also serves as a member of the National Assessments Governing Board, which oversees the construction and administration of NAEP. “You get out of something what you put into it, and we haven’t been putting enough in to get anything other than the results we’re seeing.”

A ‘neglected sphere of learning’

The new scores arrive at a period of contention around social studies, when both policymakers and members of the public allege partisan interference in classroom instruction.

Conservatives, including a swell of newly emergent parent groups, have spent much of the past few years complaining that teachers and school district leaders are indoctrinating children through ideological instruction on topics like race, gender and sexuality. Progressives counter that Republican-led moves to narrow topics of classroom discussion and remove controversial books from school libraries constitute a more pernicious form of political meddling.

In a statement, Secretary Cardona echoed some of the latter claims, arguing that the lower NAEP scores reflect the disruptive effects of COVID-19. Restricting the autonomy of teachers “does our students a disservice and will move America in the wrong direction,” he said.

“The latest data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress further affirms the profound impact the pandemic had on student learning in subjects beyond math and reading,” Cardona wrote, adding that it is “not the time…to limit what students learn in U.S. history and civics classes.”

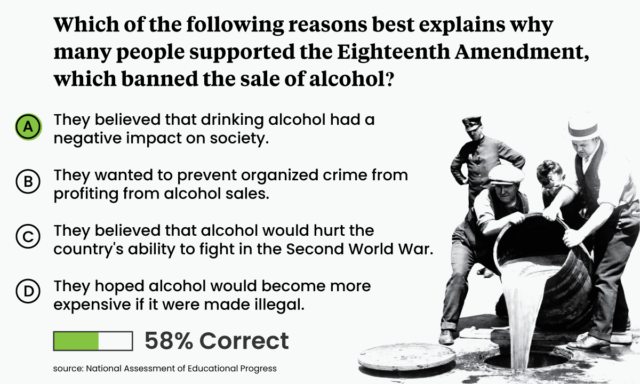

Sample question (NAEP/The 74)

But whatever the impact of recent disputes over lengthy school closures or district-led equity initiatives, the drop in history knowledge can be traced back to 2014. It was around that time that a new federal education law, the Every Student Succeeds Act, replaced No Child Left Behind — a development that many hoped would reduce classroom focus on the core subjects of math and English and make more room in the school day for instruction in science, social studies, and the arts.

If that shift occurred, it can’t be detected in the latest NAEP results. Edward Ayers, a renowned historian who serves as both a humanities professor and president emeritus of the University of Richmond, said that history education still languishes as “a neglected, de-emphasized sphere of learning” within the K–12 world.

The downward-trending performance “reflects 30 years of disinvestment in the teaching of social studies,” reflected Ayers, who recently launched an online hub called New American History to provide free learning resources to K–12 teachers. “It reflects the diminished amount of testing devoted to those subjects. We have emphasized STEM and reading and sacrificed this kind of learning in schools across the country.”

Recent findings from nationally prominent research and advocacy groups have sounded a similar note. A recent and wide-ranging survey of the elementary social studies landscape was conducted by the RAND Corporation, warning of a “missing infrastructure” for the teaching of civics and history in elementary schools. Few states require regular assessment of social studies knowledge, the study found, and many rely on low-quality standards. While 98 percent of elementary principals reported evaluating their teachers on math and reading instruction, just 67 percent said the same of social studies. A sizable majority of teachers said that the task of selecting curricular materials for social studies lessons fell to them, and just 16 percent said they worked from a textbook.

Survey responses from eighth graders who took the exam dovetailed somewhat with those findings. Between 2018 and 2022, the proportion of students who said they were enrolled in a dedicated U.S. history course declined from 72 percent to 68 percent. Just 55 percent said they had a teacher whose “primary responsibility” was teaching U.S. history, compared with 62 percent four years prior.

Ayers said that the “diminished” focus on history endangered the development of civic skills and inclinations. Only a renewed push for more and better instruction in social studies could reverse that, he said.

“I care about people living in public, living with one another. And there’s nothing like getting outside of yourself — that’s kind of what the humanities do generally. To step outside your own perspective and imagine another time, another place, another gender, another skin, is the best way to foster a sense of common purpose.”

- Read more: Commentary: Teachers are on the front lines of preserving democracy. They can’t do it alone

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter