Stockton, California: What happens when a dysfunctional district gets $241 million

Linda Jacobson | February 14, 2023

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

When Congress approved $190 billion to combat the educational devastation wrought by the pandemic, the Stockton, California, school system was practically the poster child for a district in need.

Nearly 80% of students in the Central Valley district live in poverty. High COVID infection rates were shutting down packing plants where many of their parents work, and when schools reopened, more than a third of students were chronically absent.

But almost three years after the first relief dollars began flowing to school districts, Stockton has spent only a fourth of the $241 million it received, overcome by dysfunction in its central office and deep mistrust among board members. The money it did spend has come under fire from two civil grand juries, who criticized the school board for approving at least two projects it later abandoned. And Tuesday, an independent auditor hired by the San Joaquin County Office of Education is expected to release the results of a long-awaited fraud investigation into the district’s finances.

Based on the grand jury reports — as well as documents LA School Report obtained from public records requests and numerous interviews — several questionable expenditures have emerged, including:

- $7.3 million in air filters designed to kill COVID from a firm that was not licensed at the time to do business in California — the bulk of which remain unused in a district warehouse.

- Over $2 million to cover the six-figure salaries of 14 district executives. One of them also runs a popular website that regularly targets political enemies, including student activists and teachers.

- $150,000 in startup costs to a program designed to help students make up for months of instruction lost during the pandemic. After five months of planning, the district pulled the plug after deciding it would cost too much.

“Stockton is a worst-case scenario,” said Jeffrey Henig, a political science and education professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, who studies school boards. The Biden administration, he said, distributed the relief funds as quickly as possible with “an expectation that districts would understand their needs and be able to use it intelligently.”

Instead, with seven superintendents in as many years — and the board of trustees now searching for another — the district’s recovery has stalled. It faces a $30 million deficit and risks losing control of its affairs to the county education office.

Losing patience, the community is demanding that leaders address how they plan to use the funds to benefit students.

“I hoped that class sizes would be smaller, that teachers would have some extra time to step back and help their students that are struggling,” said Michelle Munoz, who left her job in Stockton as an instructional coach last fall. She wanted the district to hire staff to find students who didn’t show up for online learning, but that didn’t happen.

Despite the relief funds, she said one school she worked at couldn’t get a carpet and other furnishings to open a “calming room” for students with behavior and trauma issues. At her most recent school, Wilson Elementary, she heard a secretary on the phone asking to buy rolls of laminate for classroom posters on credit because the board had yet to approve the district budget.

“I know it’s always been a problem, teachers having to buy their own supplies,” she said. “But now you have millions of dollars.”

A ‘crisis of self-image’

The district’s financial turmoil didn’t occur in isolation.

In 2012, Stockton became the largest city in the nation at the time to file for bankruptcy. During the housing boom, the city increased retirement benefits for its employees and financed new sports venues downtown along the San Joaquin River. But when the bubble burst, it was unable to pay its bills.

“Stockton has had — and this is reflected in the schools — really dicey economic times,” said Robert Benedetti, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of the Pacific, which has a campus in Stockton.

On top of that, he said, the city suffers from a “crisis of self-image” — labeled more than once by Forbes as America’s worst and “most miserable” city because of high unemployment and violent crime.

Before Stockton went bankrupt, the city spent millions to revitalize its downtown waterfront, including the construction of a new sports arena. (Linda Jacobson/LA School Report)

And it’s not just the city that has been singled out for such harsh critiques. “I think Stockton Unified might be the worst system in the country,” was the recent assessment of a prominent California school reformer, whose nonprofit issued a report last year decrying the district’s “inept governance.”

Even strong districts with stable leaders have struggled to spend their relief funds in the face of staff shortages and supply chain delays. By the time the money came Stockton’s way, however, the district had been beset by years of interpersonal feuding and economic malaise. Since 2017, enrollment has declined from about 44,000 to 36,000 students, contributing to anxiety in a community where over 3,000 people work for the district.

“People’s livelihoods are affected when programs shrink,” said John Ramirez Jr., who resigned as superintendent last June after just 13 months. “Of course there is going to be concern.”

‘What’s he trying to sell?’

The pandemic was another blow to the region’s economy. Then, just as schools were trying to recover, separate grand juries in 2021 and 2022 issued scathing reports that didn’t inspire confidence in the district’s ability to manage a huge federal windfall.

California impanels civil grand juries to serve as government watchdogs. In Stockton, the panels pointed to a district in disorder and a “vicious cycle” of superintendent turnover: Promising projects started under one leader would be abandoned when the next one took over.

Frequently, students paid the price.

“I know it’s always been a problem, teachers having to buy their own supplies. But now you have millions of dollars.”

—Michelle Munoz, former Stockton instructional coach

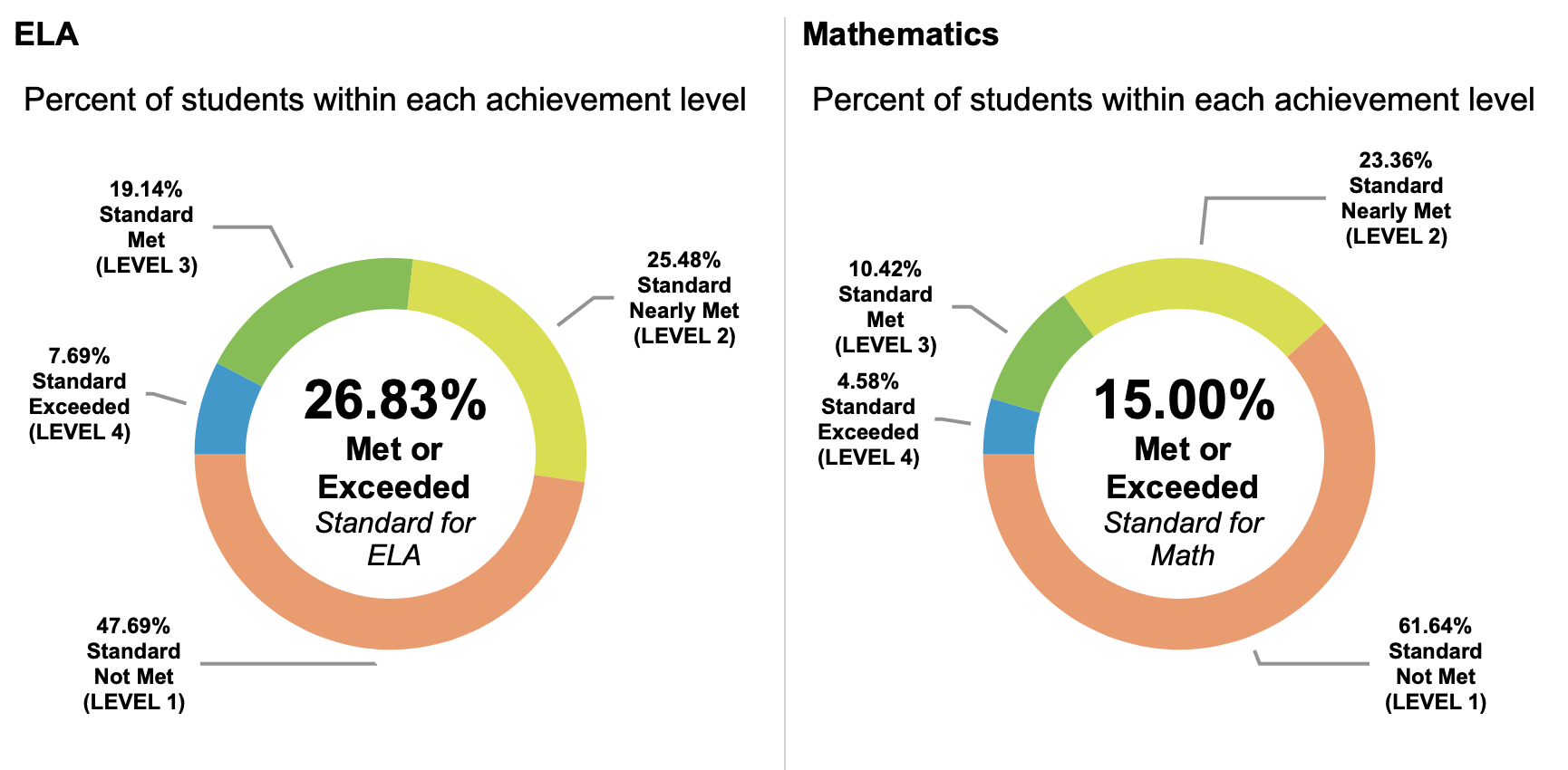

The district contracted with Educational Consulting Services Inc. of Huntington Beach to provide a Saturday program for students to make up for missed instruction — a sorely needed service in a district where 43% of students are chronically absent, 79% are not proficient in grade-level math and 73% are not proficient in grade-level reading.

But after paying $150,000 in federal relief funds for start-up costs and signing an agreement in January 2022 with the teachers union to provide instruction, efforts to launch the program ceased, according to the grand jury.

Marcus Battle, then the district’s chief business officer, called the program “a noble idea” that fell victim to poor planning. The district, he said, initially sought to roll out the program to less than 20 schools. But when leaders decided to expand it to serve thousands of students at a potential cost of “tens of millions” of dollars, he worried it would “spiral out of control” and withdrew his support.

A district spokesperson declined to discuss the episode.

Another relief-fund project that started only to be quickly abandoned was a $7.3 million investment in ultraviolet air filters designed to kill COVID. The firm hired to provide and install the filters, IAQ Distribution of San Diego, was not licensed at the time to do business in California, the grand jury found.

In part of a pattern the panel identified, the board approved the contract even though district staff rated IAQ’s proposal the lowest-quality bid out of five submitted.

IAQ installed 800 of its ultraviolet air filters in classrooms, but 1,400 sit unused in a district facility. (Courtesy of Silvia Cantu)

The district would not elaborate on why the work was left unfinished. Newly installed board President AngelAnn Flores, the lone member to vote against the contract in August of 2021, is pushing for an investigation into what she deems “misspent money.” She called the deal “bogus” and said the district is planning to sue IAQ to recoup $6.6 million.

Neither IAQ nor its parent company, Alliance Building Solutions Inc., responded to calls or emails seeking comment.

Ultimately, only 800 of the 2,200 filters the district paid for were installed. The rest are sitting in a district warehouse.

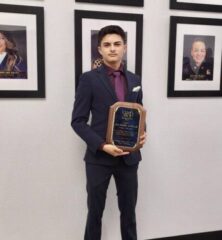

AngelAnn Flores was sworn in for a second term on the board in December. (Stockton Unified School District)

The example is one of several cited by the grand jury in which the board of trustees that oversees the school system made “crucial decisions with minimal data, knowledge and consideration.”

In the case of IAQ, the impetus for the deal appears to be a lifelong connection between a former board member and Anthony Silva, a former Stockton mayor with a long list of legal troubles.

“I heard about it through Anthony Silva,” Scot McBrian, a trustee at the time, told LA School Report. “My first thought was, ‘What’s he trying to sell?’ I asked him if he had any financial interest in it and he said no.”

McBrian said he’s known the former mayor since they played chess when Silva was a teenager. Aside from the tip from an old friend, he said the filters reminded him of an air purifier he used to sell in Texas and later installed in his home. After recommending that Alliance give a presentation on the devices, McBrian told the board that IAQ should be considered a potential vendor.

Without elaborating, the grand jury said, “The practice of a trustee recommending a vendor is unusual and may be considered or perceived as a conflict of interest.”

Oprah’s candidate vs. the ‘underdog’

Silva — and his successor as mayor, Michael Tubbs — play an outsize role in the psychic landscape of the city. Once a school board member who called himself the “people’s mayor,” Silva, a Republican, is a Stockton native who worked to rebuild the city’s police force and provide jobs for the homeless as it emerged from bankruptcy. He frequently warned of “outside forces” he said were trying to influence the city’s agenda.

“People see him as an underdog and he always seems to be advocating for the underdog. I think that sometimes resonates with this town,” said Jose Rodriguez, executive director of El Concilio, a nonprofit that runs preschool programs in district schools and opened a charter this school year.

“I think Stockton Unified might be the worst system in the country.”

—Don Shalvey, California charter school developer

A Stanford graduate, Tubbs leapt to national prominence when Oprah Winfrey donated $10,000 to boost his early political career. He sought support from outside donors, including those that embraced charter schools, and backed reformer John Deasy, who served as superintendent of the Los Angeles schools before running Stockton Unified from 2018 to 2020. Tubbs is best known for launching a guaranteed basic income program to help the city’s poorest residents and now advises Democratic California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“He was talking about programs that were of national interest,” said Benedetti, the University of the Pacific professor. “He was not seen as a local in any way, and there was nobody to tout him as one.”

Silva’s star dimmed following a series of arrests. In 2016, he pled guilty to a misdemeanor charge of providing alcohol to a minor in connection to a strip poker game at a camp he ran for low-income youth. The following year, he pled guilty to felony conflict of interest. Prosecutors said he transferred $5,000 from a mayor’s fund to the Stockton Kids Club, where he served as CEO, and used club donations for personal expenses, including trips and online dating.

In 2022, Silva, who now runs a family entertainment business called Indoor Adventures, successfully moved to have the conflict of interest charge reduced to a misdemeanor and got the conviction expunged from his record. Multiple attempts to reach him by phone and Facebook, and through two attorneys, were unsuccessful.

Though 2020 was the last time either man occupied City Hall, support for them remains a kind of district shorthand: Silva’s backers see themselves as defending the traditional school system from privatization, while Tubbs’s supporters say they want alternatives to a punishing status quo.

But if Silva disappeared from public life, it’s often hard to notice.

In 2021, three members of the board of trustees sued Flores, the current board president, in part because she accused them of being Silva’s associates. She countersued on First Amendment grounds, and even though the trio later dropped the case, a county judge ruled that they need to pay Flores over $19,000 in attorneys fees. Silva also sued her for defamation over comments she made at a March 2021 meeting regarding his conviction for serving alcohol to a minor. A hearing on that case is scheduled for March 21.

“I’m seen as controversial and uncontrollable,” Flores said.

In recent years, shouts of “Out of order!” have dominated board meetings. The grand jury condemned the board for its frequent use of complaints and censures against trustees in its voting minority, which at the time included Flores.

‘Reform politics’

The tensions in Stockton often arise from a sense of hopelessness in a city where achievement was stagnant even before the pandemic.

“Folks have not had results for a long time. If I’m a parent, I’m going to be concerned about that,” said Ramirez, the former superintendent. With “second-, third- and fourth-generation students in poverty, we’re not going to make a change in our community until they have an opportunity to succeed.”

Ramirez sidestepped questions about district controversies during his tenure, citing the terms of his severance agreement, which continued his $285,000 salary for an additional year. But did note that the persistent toxicity tends to overshadow even legitimate accomplishments.

A successful online tutoring program — now in more than 40 districts nationally — got its start in Stockton, and the graduation rate, he said, has increased from 79% to 83% since 2018. The district also plans to spend at least $9 million in relief funds to upgrade science labs and career education programs.

But many families aren’t waiting for the district to improve. More affluent parents among Stockton’s 320,000 residents tend to put their children in private schools or move to the neighboring Lincoln Unified district, which has a lower poverty rate and higher-performing schools. Roughly 6,000 Stockton students attend charter schools.

Trustee Ray Zulueta Jr. sees the grand jury and fraud investigations as proxy attacks by community members affiliated with “multiple groups donating millions of dollars to education reform politics in Stockton.”

Don Shalvey

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, for example, awarded $1.37 million in 2020 to the Community Foundation of San Joaquin to expand an “early college” model that allows students to earn college credit in high school. And the City Fund, which supports nonprofit organizations opening charters, donated $1.2 million last year to San Joaquin A+, led by Don Shalvey, the California charter school pioneer who released the damning report on Stockton schools and founded Aspire Public Schools. Shalvey spent 11 years at the Gates Foundation, and the Aspire network now has 10 sites in Stockton. (Both the Gates Foundation and City Fund provide financial support to LA School Report’s parent company, The 74; donors play no role in newsroom editorial decisions.)

To Zulueta, these are “liberal institutions … working hand in hand with big business entrepreneurs to control localities through takeovers of public education systems.” Campaign donations from local reformers, he said, have favored Democrats on the board who support “political movements like [Black Lives Matter] and defund [the] police.”

Aspire Public Schools has 10 locations in Stockton. (Aspire Public Schools)

209

In most districts riven by reform fights, the most formidable enemies of school choice are typically teachers unions.

But in Stockton, the two groups have found common cause. They mutually endorsed four members for school board, all of whom won in November. Along with Flores, who took over as president, they now hold the majority on the seven-member board.

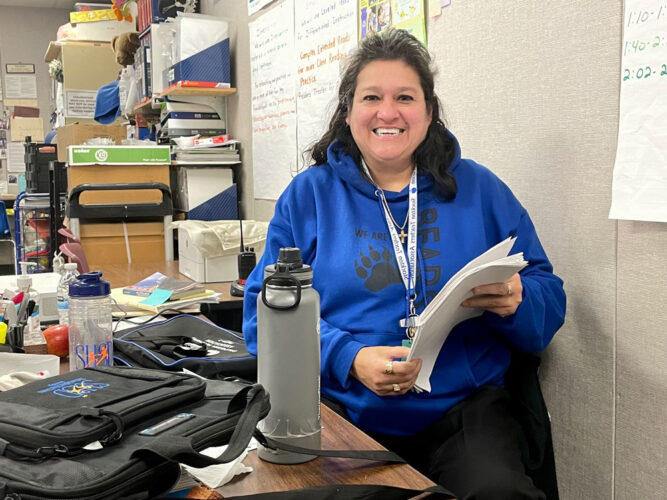

Silvia Cantu, a sixth-grade teacher at Washington Elementary School, has been a critic of the district’s use of relief funds. (Linda Jacobson/LA School Report)

Silvia Cantu, a sixth-grade teacher at Washington Elementary and a member of the Stockton Teachers Association, said she supported the candidates because she didn’t like the direction the district was going under the previous board.

“I did not want [Stockton Unified] taken over” by the county, she said. The former trustees, she added, “mostly spent millions of dollars on administration. [The money] won’t trickle down to the classroom.”

“Nothing you can do will save these devils. I have big plans for all of you.”

Motecúzoma Sanchez, founder, 209 Times

The success of these strange bedfellows put both groups in the crosshairs of Motecúzoma Sanchez. In a city full of brash personalities, there is perhaps none so aggressive as Sanchez, founder of the incendiary 209 Times, a popular website named for the region’s area code.

The website characterizes the candidates who now lead the board as pawns controlled by “greedy millionaires” and “outside corporate interests” set on luring Black and Hispanic families into charter schools. The site posts unflattering-as-possible photos of board members, teachers and even students who raise concerns about the district’s finances and portrays them as part of a larger plot to expand charters.

The seven-year-old site has grown as the local newspaper lost readers, from almost 60,000 20 years ago to about 33,000 today.

“I destroyed them and took over as the dominant media source for the region,” Sanchez boasted in an email to LA School Report.

During the 2022 election, the 209 Times accused teachers in the union, by name, of trying to “fool unsuspecting parents” into voting for the four candidates. In a typical example, it mocked a former Stockton Unified student — now 26 and a member of the advocacy group FixSUSD — by posting her photo next to Fiona’s, the ogre princess from the movie Shrek, with the caption, “Who wore it better?”

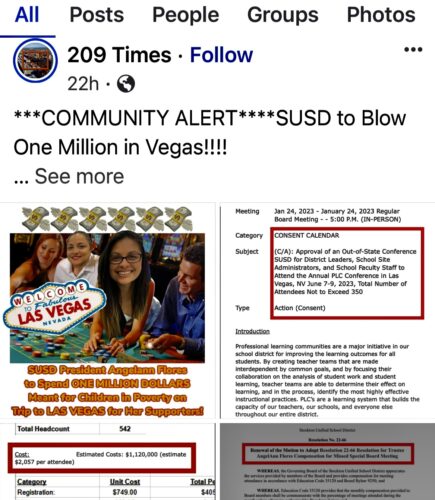

209 Times has accused the Board of Trustees and president AngelAnn Flores of wasting money for approving $1.1 million to send 540 teachers to Las Vegas this summer for a conference. The district is not using relief funds to pay for the trip. (Screenshot from 209 Times)

Out of fear of being shamed by the site, several district employees contacted by LA School Report asked to remain anonymous. The irony is not lost on them that the source of their fears is a colleague — one who serves as the face of the district’s efforts to welcome families and help those in crisis.

Since 2021, Sanchez has been director of the district’s family resource center. During his tenure at Stockton Unified, federal relief funds have been paying his yearly salary, now at $141,000.

Sanchez didn’t respond to questions about his salary or his treatment of political opponents. But in another email, he accused a 74 reporter of being “a paid shill” for charter developer Shalvey and “the national charter school movement.”

Motecúzoma Sanchez, director of the district’s family resource center, also runs a website that campaigned against the current school board majority. (Twitter)

“Nothing you can do will save these devils,” he wrote. “I have big plans for all of you.”

According to the district, Sanchez is just one of 21 current and former high-ranking central office employees who have been paid with relief funds.

Another is Armando Orozco, who earns $150,000 a year as director of facilities. In September, the district placed him on paid leave after he sent an email to current Interim Superintendent Traci Miller demanding $800,000 to stay silent about “corrupt and erroneous actions” in the district.

Orozco could not be reached for comment, and the district declined to make Miller available for an interview.

The head of the agency conducting the fraud investigation has already indicated that paying department directors out of relief funds is a sign of financial distress.

“If you’re going to have them in the central office, the implication is that they are there to stay,” said Michael Fine, CEO of the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team, “Why would you be using one-time funds?”

‘Personalities and vision’

After running on promises of greater transparency, the new board is under pressure to produce results.

On top of the projected budget shortfall, a fraud investigation and a long list of grand jury recommendations it has yet to implement, the district has just a year and a half to show it can responsibly spend its remaining $180 million before hitting a congressional deadline to obligate the funds.

“We didn’t get here overnight,” explained board president Flores, a 45-year-old substitute teacher and former afterschool program leader.

In one of its first official acts, the board in January devoted an entire meeting to informing the public on how relief funds have been spent. Staff, teachers and community members packed the board room of the district’s modern administration building, about a block from the waterfront.

From left, Trustees AngelAnn Flores, Kennetha Stevens, Alicia Rico, Ray Zulueta Jr, Cecilia Mendez (Linda Jacobson/LA School Report)

Flores, who asked many of the questions, seemed underwhelmed by a series of PowerPoint slides the district provided displaying lump sums for items like transportation, instruction and maintenance.

“I was expecting a little more detail,” she said, drawing applause from several observers. She later referenced “illegal” facility contracts, but offered no specifics.

Cecilia Mendez, the former board president — and among those who sued Flores — waved off any suggestions of financial mismanagement.

“This board has done nothing wrong,” she said.

Before the trustees took their seats, a district employee placed a small bamboo plant and a copy of The Giving Tree next to each name plate. She reminded them of the adage about money not growing on trees, stressing that the relief funds require “monitoring and care.” In the book, the tree gives everything to its ungrateful owner until there is nothing left but its stump.

For about a year and a half, Zachary Avelar sat in one of those seats. Despite losing in November, he does not seem sad to have left it all behind.

“I did not enjoy local politics,” said Avelar, who was just 22 when he joined the board. “Everyone says they’re about helping children, but we both know that’s not true. People here fight over personalities and vision.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.