Teachers find coaching helpful but most don’t get enough of it, survey says

Mikhail Zinshteyn, CalMatters | February 24, 2020

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

School staff who coach teachers to become better at their craft can be one approach to improving student outcomes, but few coaches have the time and administrative support to do their jobs effectively, a new survey finds.

School staff who coach teachers to become better at their craft can be one approach to improving student outcomes, but few coaches have the time and administrative support to do their jobs effectively, a new survey finds.

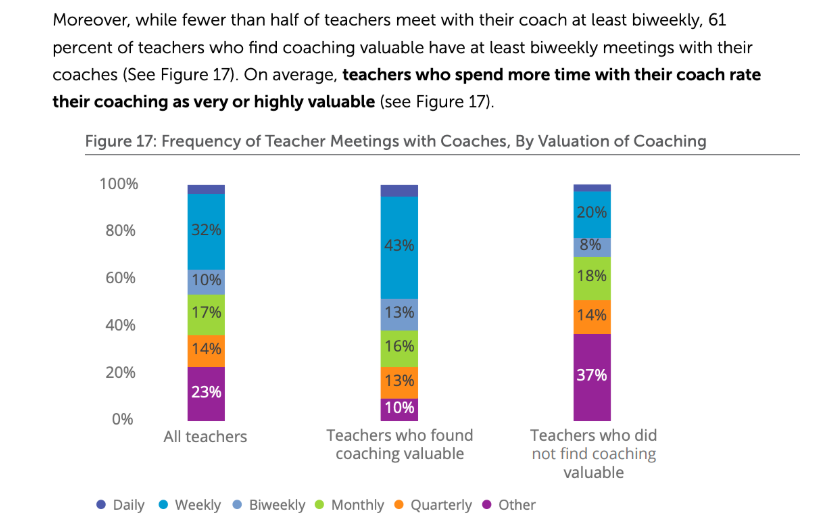

A large number of teacher coaches surveyed say they oversee at least 16 teachers, more than the recommended 10 teachers per coach. And while teachers report finding value in receiving biweekly coaching, most see their coaches less frequently and in shorter durations than teachers would like.

The results are from a survey of more than 1,000 active coaches by Digital Promise, a nonprofit that promotes digital tools in education, and Learning Forward, an educator professional development nonprofit. Google for Education also took part in the survey’s release.

Digital Promise and Google for Education previously worked together to place coaches in schools and monitor the impact extra training had on student learning. After two years of observation, teachers with regular access to coaches felt more confident and had their students collaborate more through technology, a 2019 report said. Teachers trained by coaches also reported increased engagement from their students. Those coaches each supervised the progress of an average of nine teachers over eight-week periods.

Academic evidence exists that says coaching — a broadly defined term that involves coaches observing teachers and providing feedback — can lead to teacher improvement. A 2018 meta-analysis of several dozen studies published since 2006 shows that the benefits of coaching are some of the most significant among all types of school-based interventions and are “larger than differences in measures of instructional quality between novice and veteran teachers.” Most of the studies focused on early grades due to federal support for improving student reading levels. A majority of the studies also evaluated coaching that was paired with some other professional development service, such as training for an instructional approach. But few of the studies looked at the effect coaching had after the support ended.

Teacher coaches wear multiple hats at schools and districts. According to the just-released survey, which collected responses last October, 40 percent of school-based coaches are also classroom teachers. Combined with seeing 16 or more teachers, “that’s a pretty heavy workload for coaches,” said Kasey Van Ostrand, project director of the Dynamic Learning Project at Digital Promise and an author of the survey report. She spoke during a webinar highlighting the report’s findings that also included perspectives from current teacher coaches.

Danielle Johnson, a teacher coach at a middle school near Dallas, said the report’s finding that coaches need their own coaches resonated with her. She had access to a mentor who checked in with her monthly via online chats.

“Teaching kids is hard. Teaching grown-ups is very hard, and I don’t know that I would have been emotionally supported as well had we not had that mentorship,” Johnson said. “I’m not a counselor, I’m not a psychologist, so I didn’t have training in that, but my mentor did.”

Johnson said a coach can offer an array of services to teachers, from acting as a sounding board for new instructional approaches to finding district policies on how to report data that teachers don’t have time to research themselves. Having coaches on campus whom teachers can visit at a moment’s notice is useful for those reasons, she added.

Another coach advised that schools and districts shouldn’t refer teachers to coaching as punishment. Teachers should be rewarded for wanting to improve their craft and consult with staff on the best ways to roll out a new teaching plan or strategy.

The survey report’s authors recommended several reforms to how coaching is coordinated and funded at schools and districts. Much of the funding for coaches comes from U.S. Department of Education Title II funds meant for teacher improvement. Most coaching positions, according to the survey, are funded on a year-to-year basis rather than receiving funding for multiple years. The report recommends dedicated funding from state or federal coffers for coaching.

The Trump administration this week proposed rolling Title II funding together with numerous other federal education programs as part of a $4.7 billion cut overall to those programs, according to Education Week. The budget is unlikely to persuade lawmakers, who in the past two years have funded education programs the Trump administration sought to downsize or remove.

Coaching costs have ranges of $3,300 to $5,200 per teacher, the meta-analysis said. Still, “Given the billions of dollars U.S. districts and others around the world currently spend on PD, coaching should not be seen as prohibitively expensive from a policy perspective,” the researchers wrote.

Other recommendations in the Digital Promise report include ensuring that teachers see their coaches for 30 minutes biweekly, keeping coaching workloads down and encouraging coaches to use digital technology for more regular check-ins with the teachers they mentor.

“Happy teachers means effective students, means lower turnover,” said Johnson, the coach. “It means fewer sick days or mental health days, and it means that teachers are more excited about what they’re doing in the classroom.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.