The achievement gap has driven education reform for decades. Now some are calling it a racist idea

Kevin Mahnken | August 21, 2020

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

For decades, a coalition of educators, politicians and activists have fixed one goal above all others in their mission to promote equity in education: closing the racial achievement gap.

Its very existence — the stubborn divergence in standardized test scores between white students and students of color — belies the progressive dream of a color-blind classroom. Year after year, with each new release of the results from mandatory state exams or the National Assessment of Educational Progress, Americans are confronted with the reality that educational mastery in core subjects like math and reading is largely segregated on lines of race and class.

A generation of education policy has been shaped in part by an extended discussion around racial differences, and the lingua franca of that dialogue is testing data. Achievement gaps are at the heart of school improvement initiatives led by states, cities, universities and philanthropies, and civil rights groups like the NAACP and the Urban League have organized vigilantly around the exam performance of minority children.

- Related: San Francisco schools: NAACP urges ‘state of emergency’ over city’s stark racial achievement gap

But there is new reason to think that the persistent focus on testing and disparities may yield unintended ill effects. An experimental study conducted by David Quinn, a professor at the University of Southern California, found that media coverage of the achievement gap “may have increased viewers’ implicit stereotyping of Black students as less competent than [white] students.” The negative perceptions were formed in response to a television news segment just two minutes long.

The research comes at a time when prominent thinkers are re-examining the logic of the achievement gap and its starring role in education debates. While most believe that assessment should continue to inform school evaluations and accountability, some question whether the construction places responsibility for disappointing test scores on the heads of students themselves.

Others go even further, condemning standardized testing as a weapon of white supremacy. The historian Ibram X. Kendi, whose books on race have vaulted up the best-seller lists in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, has argued that the idea of an achievement gap is the residue of a “racial hierarchy” rooted in bigoted intelligence testing from the turn of the 20th century.

The issue has become a fault line cutting across the education world. Chris Stewart, CEO of the advocacy group brightbeam and an often sharp-tongued voice for reform, said in an interview that the instinct to discard testing is “powerfully misguided” and that educators must grapple with the uncomfortable fact that African-American and Latino students’ scores are lower on average than those of their white and Asian-American peers.

“I get the inclination to want to rephrase things because you have a political or sociological goal, but that’s not actually in keeping with reality,” Stewart said. “I’ve often joked that you could call it ‘dry cleaning’ if you wanted. But the phenomenon beneath what you’re calling it is the same, and the most truthful way to term that is an achievement gap.”

But Shavar Jeffries, head of the group Democrats for Education Reform, countered that the phrasing was bound to heighten racial stereotypes about student groups that cannot or will not “achieve.” While maintaining that student assessment is a necessary component in the fight for better schools, he said that policymakers would do better to highlight the “opportunity gap” — the distinctions in wealth, status and geography that unfairly exclude some populations from good schools. He said it was clear that this divide in circumstances, not innate ability or willingness to work, is responsible for differential outcomes.

“‘Achievement,’ at least the way I think about the word, means that the individual has achieved something, that they’ve performed in a certain type of way,” Jeffries said. “If we name this [disparity] an ‘achievement gap,’ particularly in a country that has a racist history, it reinforces a context where people are already predisposed to think that certain folks of color can’t achieve the same way as others. You can call it marketing if you want, but I think how we frame things matters.”

A ‘problematic’ narrative

The public has long been aware of the inequalities built into the nation’s patchwork agglomeration of state-based school systems. But the achievement gap as a phenomenon of political crusades and scientific study is a modern creation of the education reform era.

The proliferation of widespread, high-stakes standardized testing, accelerated by the 2002 passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, compelled school districts to assess and report the progress of various student racial groups toward academic proficiency. State and federal reforms launched since that time have in some cases reduced, but not eliminated, the importance of assessment and accountability.

Lynn Jennings has observed the long life of the achievement gap as both a former teacher and a senior staffer at the Education Trust. Although the concept held a rhetorical power at the dawn of the reform era, she believes its usefulness is “sunsetting.” Like Jeffries, Jennings said that it miscasts students as the sole agents in their own academic growth, ignoring structural factors like poverty and prejudice.

“I think for reform groups — and I put EdTrust in that category historically — the shift away is a good thing,” she remarked. “What we had to do 20-something years ago, to make that case and show numbers and charts and graphs, it has been made. Any kind of narrative that something is wrong with Black students and Black children is problematic.”

Some in the academy share those misgivings. Ron Ferguson, an acclaimed economist who has studied education and youth development his entire career, confessed that he worried about how coverage of racial differences in test scores could amplify negative generalizations about minority students. His concern is particularly striking given that Ferguson leads an influential research project at Harvard called the Achievement Gap Initiative.

In an email, Ferguson stressed the importance of boosting the prospects of disadvantaged students through improving instruction, curbing negative peer pressure and working with parents to foster a better learning environment at home. At the same time, he warned that the level of public attention paid to testing gaps could backfire.

“We can do these things with the goal of narrowing gaps … without dwelling on the gaps in the media. The latter contributes to stereotypes and also discourages the children of color who read those same media reports.”

In a working paper released in June, Quinn, the USC researcher, specifically examined the impact of that media coverage on the public’s assumptions about intelligence and academic attainment. Over three experiments, he showed participants one of several videos: a local news broadcast detailing racial achievement gaps in state test scores, a promotional clip for a Harlem charter school, or a control video with no references to race. Viewers were then told the national high school graduation rate for white students (86 percent) and asked to guess the corresponding rate for African Americans.

Quinn found that participants who were randomly assigned to view the achievement gap video subsequently underestimated the true rate (78 percent) by as much as 29 percentage points, roughly seven points more than those in the control group. The effects faded at a two-week follow-up assessment, but Quinn said that the study offered preliminary evidence of how “achievement gap discourse” could diminish people’s views of minority students.

“It’s not an argument that we need to stop talking about these inequalities,” he said. “It’s an argument that we need to think carefully about the way we talk about them, because the way in which we talk about them affects the way that people understand the issues.”

Shell game?

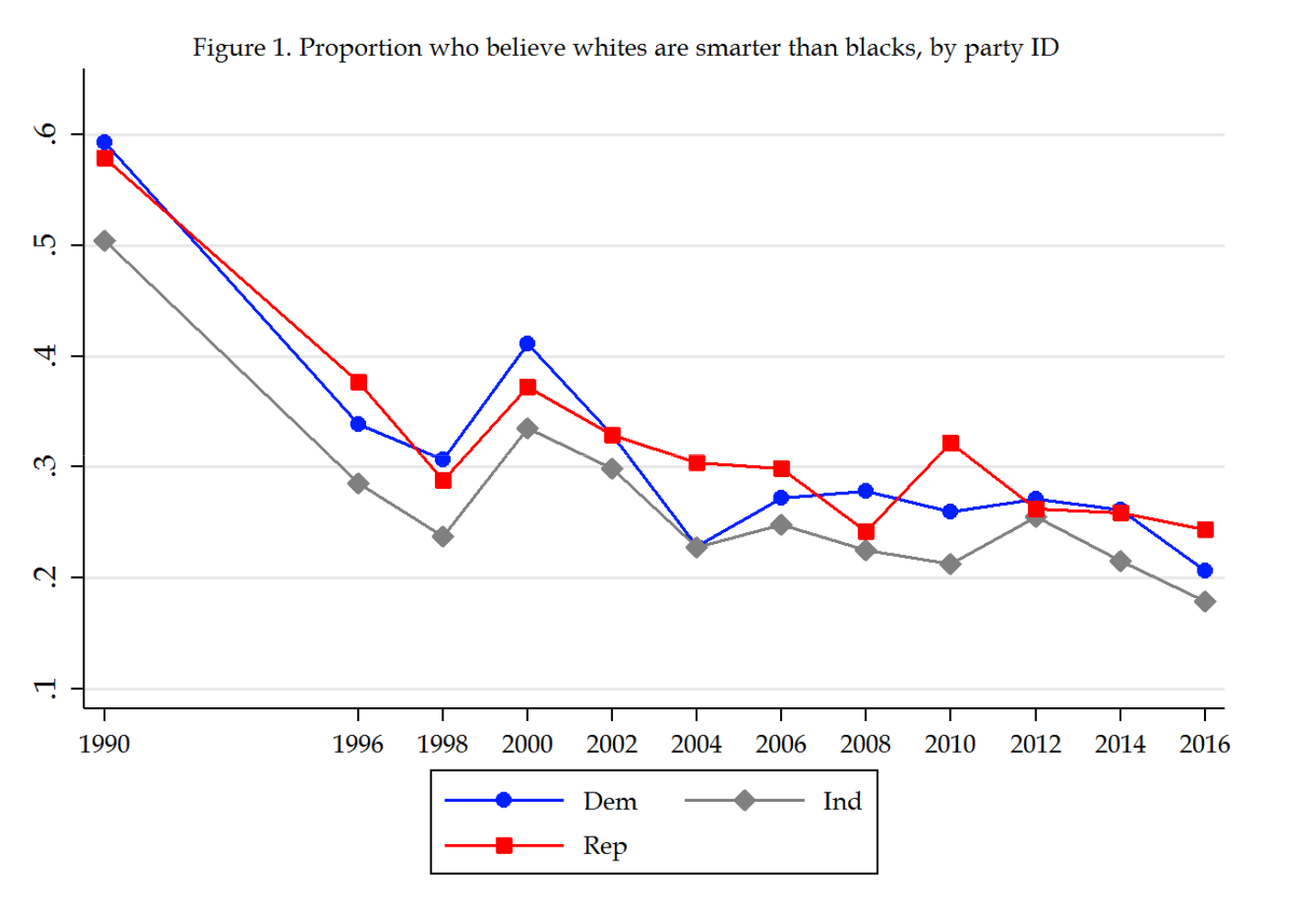

For most of the time that Americans have been exposed to news and analysis about the achievement gap, their beliefs have generally been moving in a more egalitarian direction with respect to race. The General Social Survey, a sociological poll funded by the National Science Foundation, has regularly asked respondents about their opinions on the relative intelligence of racial groups over the past three decades. Although 23 percent of white respondents still believe that African Americans are less intelligent, that portion has declined significantly since 1990, when over half held that view; 8 percent of white respondents said that African Americans were more intelligent than whites.

Jeffries’s personal acquaintance with the effects of stereotyping came early. A first-generation college student from a poor neighborhood in Newark, he placed near the top of his high school class but was initially encouraged to apply to colleges that were far less competitive than his grades warranted. When he enrolled at Duke University, his classmates sometimes assumed he had been recruited as an athlete.

“I was like, ‘I don’t play football, I actually have a full academic scholarship,’” he recalled. “But there was a certain stigma associated with my skin color.”

Jeffries doesn’t call for the abolition of testing and accountability regimes, but he is concerned that the intense focus on differential test scores could strengthen America’s existing tendency toward prejudice and low expectations. Those differences, he and others argue, merely reflect the ways in which minority and low-income students are denied access to critical learning resources, from preschool to experienced teachers to rigorous curricula.

“When you have the racial history that we have in this country … you don’t want to add on top of that some additional misleading classification that obscures the ways in which these underlying opportunities are not evenly distributed, whether it’s across race, class or other categories,” Jeffries said. “Every piece that reflects these underlying stereotypes is problematic; since it’s really an opportunity gap, why are we calling it an achievement gap?”

To brightbeam’s Stewart, that reasoning is a kind of shell game deflecting attention from outcomes to inputs. Both are important, he said, but achievement tests play a vital role in forcing schools to acknowledge and account for the underperformance of African-American kids.

In doing so, they often make an urgent case for school improvement to help those children succeed. For example, testing data are frequently marshaled by plaintiffs as evidence in school equity lawsuits (Michael Rebell, a veteran civil rights attorney who won a landmark case to reform New York’s school finance system, has said that No Child Left Behind was “enormously helpful to us from a litigation point of view”). Conversely, Stewart said, they can provide examples of minority-majority schools that actually succeed in transcending the achievement gap, including those in the charter sector.

“You can take any bit of information and use it to deflate public esteem for non-white people,” Stewart said. “The only thing that really beats that back is achievement. If there’s anything that I think is problematic about achievement gaps, it’s that it always focuses on the kids at the wrong end of the gap rather than those at the right end. We study failure more than success, and that gives the impression that there is no success.”

For the moment, many in the world of education advocacy appear to be migrating toward Jeffries’s position. Teach for America, which has often been a lightning rod within the reform community, announced two years ago that it would shift from discussing the achievement gap to the opportunity gap, saying that “it’s important to use language in a solutions-oriented way that promotes systemic reform and empowers communities to demand more.”

In the eyes of some critics, however, such changes don’t go nearly far enough. Jamaal Bowman, a Bronx teacher and principal headed to Congress after defeating a veteran Democratic incumbent, has promised to sponsor legislation that would end federal testing requirements, calling their existence a “test-and-punish regime that stigmatizes, labels, and ranks students.”

Bowman’s proposal wouldn’t stand much chance of passing, even if Democrats win unified control over Congress and the White House this November. But it echoes language in the Democratic Party platform from 2016, as well as the recommendations recently issued by an education advisory panel convened by Joe Biden’s presidential campaign. The latter document, which was heavily influenced by America’s two largest teachers unions, commits the party to ending high-stakes testing requirements and encouraging states to adopt “multiple and holistic measures that better represent student achievement.”

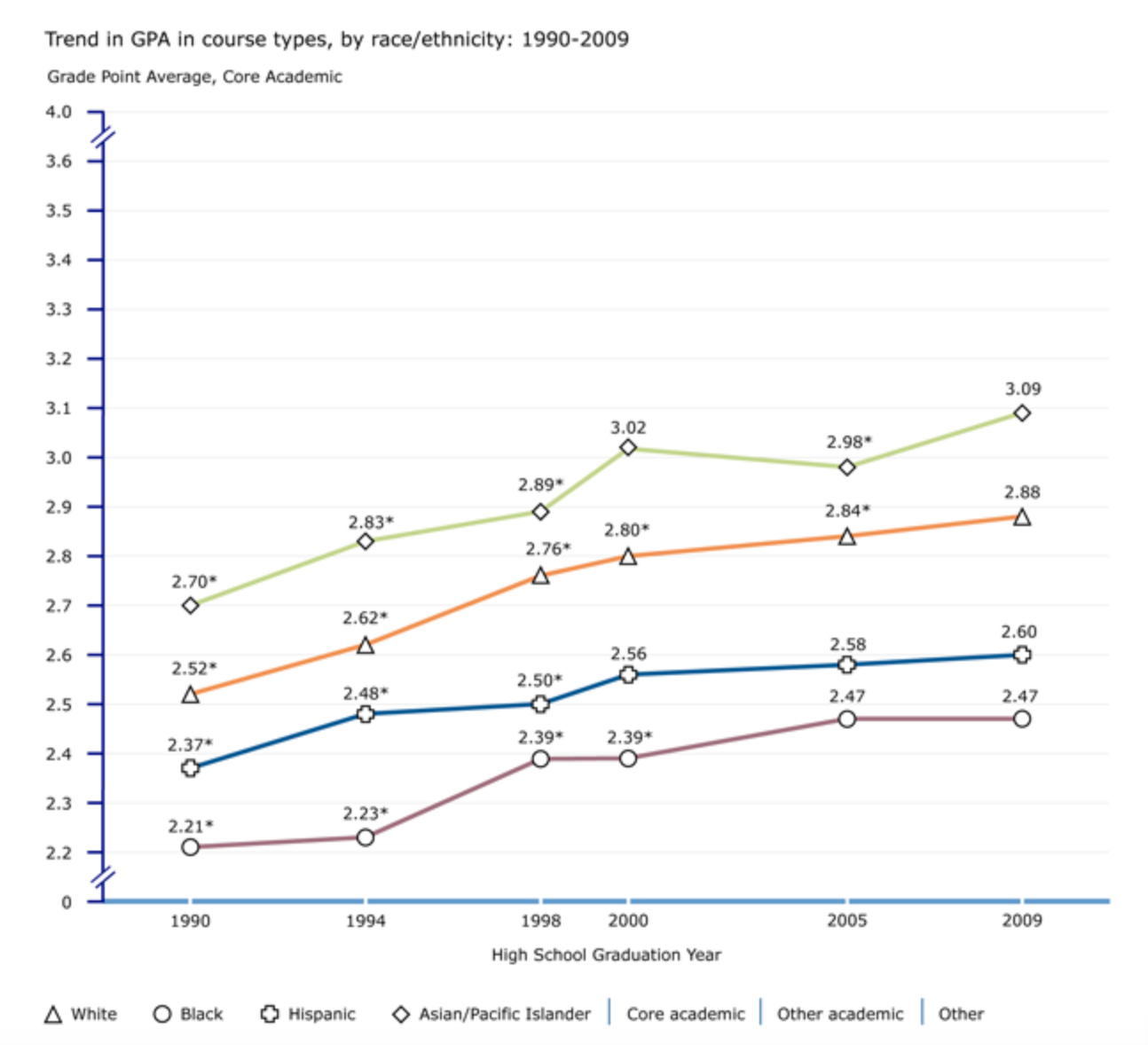

It is difficult to know what form those measures might take. Many have suggested that high school grade point average offers a more comprehensive picture of academic achievement and greater predictive insight into how students will perform in college. But a long-range study of high school transcripts conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics between 1990 and 2009 found that students’ GPA was also divided by race; in fact, over the years studied, racial gaps in core subjects like math and reading only grew.

Kendi — perhaps the most sought-after public intellectual of the moment — contends that a focus on achievement gaps, no matter how well-intended, is an inevitable handmaiden of racist thought. Rejecting the notion of a test-based standard to measure what individual students should learn from school, he has written that different learning environments produce “different kinds of achievement”; in a more recent interview with the New York Times, Kendi said that a truly multicultural America would have to make room for “multiple understandings of what achievement is and what qualifications are.”

That kind of reasoning makes the Education Trust’s Jennings uncomfortable. Decades after the emergence of the achievement gap as a fixture in policy discussions, she counseled educators and advocates to “be careful” in their language around testing and remember that “achievement is more than just a test given once a year.” But she also flinched at the idea of schools abandoning unitary standards of learning, saying that “there are certain things that you expect kids to get out of school and education. It’s a problem if you’re an eighth-grader and you’re reading on a second-grade level.”

“My mother’s from Alabama,” she concluded. “To hear her talk about her experience and what was expected of students in her segregated school versus the [white] schools, it would probably scare the mess out of her to hear that we might have different standards for different students.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.