‘The bottom has dropped out’: Study confirms fears of growing learning gaps

Beth Hawkins | November 17, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

In the earliest weeks of the pandemic, researchers associated with NWEA made two jaw-dropping predictions. The first — that school closures would lead to lower math and reading scores — has been borne out over and over since then.

The second — that the already broad range of academic levels within classrooms would yawn wider — has now been confirmed.

Before the pandemic, the average fifth-grade class had students whose learning spanned seven grade levels. But in May 2020, NWEA, the nonprofit behind the widely used MAP Growth assessment, predicted that this variation would grow as the lowest-scoring students would fall two years behind. Because the exams are not given before third grade, the researchers warned then that their findings might not reflect students whose levels of understanding are even lower.

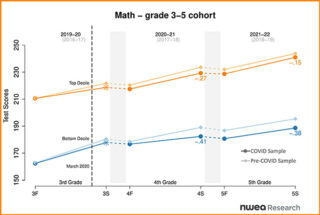

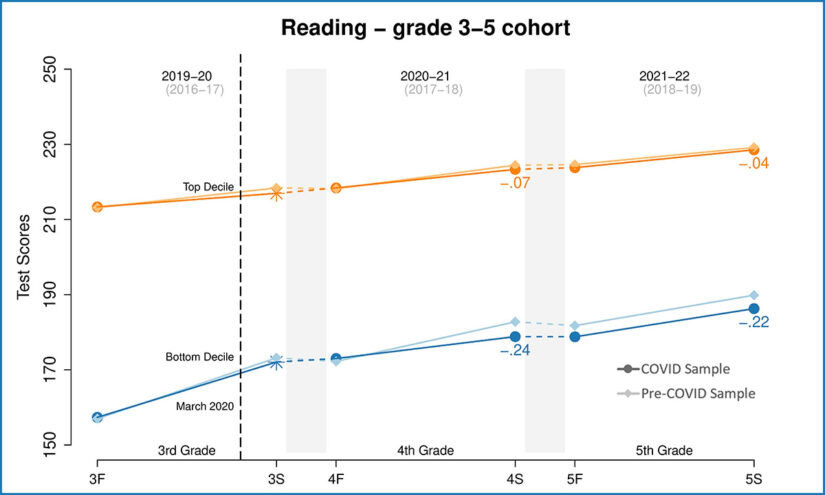

New NWEA research finds this range has increased by 5% to 10%, with the losses disproportionately affecting low-performing students. While all pupils made less progress than they would have without COVID-19’s interruptions to instruction, children who were already struggling academically have fallen much further behind.

The findings mirror the recently released dismal results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which showed that, collectively, U.S. students lost two decades of academic growth. That exam, too, showed widening gaps between affluent, advantaged students and low-income children, those learning English and students with disabilities.

Because the MAP is administered at least twice a year, researchers were also able to more precisely identify when learning stalled, and how quickly — and for whom — it rebounded. Across the board, drops in math and reading occurred during the 2020-21 school year, with high achievers losing less ground than their struggling peers.

In 2021-22, those who already performed in the highest 10% of students made more progress toward academic mastery than would have been expected absent COVID, while the lowest performers have languished.

“If we think of the range of test scores, we see that the ceiling has remained stable,” says Karyn Lewis, director of NWEA’s Center for School and Progress. “But the bottom has dropped out.”

Note: Average test scores for top decile students are shown in orange and bottom decile students are shown in blue. The lighter shade represents the pre-COVID sample and the darker shade represents the COVID sample. Decile group is determined by starting achievement status. The top decile includes students who scored at the 90th percentile or above and the bottom decile includes students who scored in the 10th percentile or below. Percentiles are calculated based on the 2020 MAP Growth norms (Thum & Kuhfeld, 2020). Spring 2020 means are asterisked because they are based on approximately 5% of the students relative to other terms due to testing interruptions during COVID school closures. Standardized mean differences between the COVID and the pre-COVID sample within achievement decile are shown below the COVID sample lines, with negative values indicating that the COVID sample scored lower than the pre-COVID sample. (NWEA)

To arrive at the findings, researchers crunched two sets of numbers. They compared scores from 8 million students in grades 3 to 8 from 2019 through 2022 with those of students who were tested in the three academic years before the pandemic. They also examined data on 1 million students who, pre-pandemic, scored in the top and the bottom 10%.

A secondary concern surfaced by the data is that the already inequitable process of identifying which students receive gifted and talented services and access to other higher-rigor academic opportunities will skew further in favor of affluent and white children, who backslid the least in the pandemic.

The widening array of mastery levels has profound implications for teachers. Pre-pandemic, most struggled to reach students at varying grade levels. As it became clear that NWEA’s first “COVID slide” warnings were, if anything, understated, debate arose about whether to continue grade-level instruction or drop back and remediate students who were far behind. Some researchers favor a strategy known as acceleration — teaching all students age-appropriate material while using data to identify specific missing skills.

To reach all children in a single class effectively, their teachers now must understand not just the academic standards for their grade, the researchers suggest, but the material for one to two grade levels above and below.

“I do think it begs the question of what do we expect each individual teacher to be able to do,” says Lewis. “I think we have to be honest that there’s a limit to teachers’ ability to be all things to all students.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.