‘Wake-up calls’: New parent survey shows 9% enrollment drop in district schools

Linda Jacobson | September 26, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

With state data projecting at least 10% drops in student enrollment over the next decade in some California counties, superintendents are worried.

“Some of them are scratching their heads, saying ‘This is something we didn’t expect, and it is hard to know if this is our new enrollment trend,’” said Suzanne Speck, executive vice president of Sacramento-based School Services of California. Registrations are pouring in for a webinar the consultant group is holding next month on declining student enrollment. “So much has been on their plates for the last 30 months.”

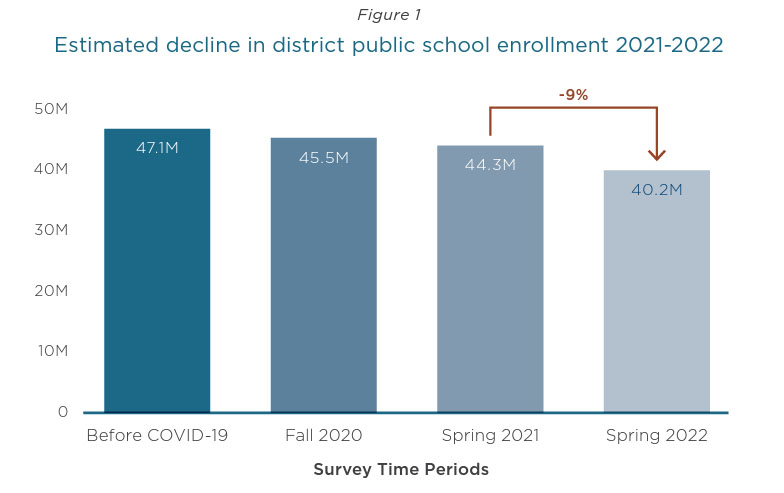

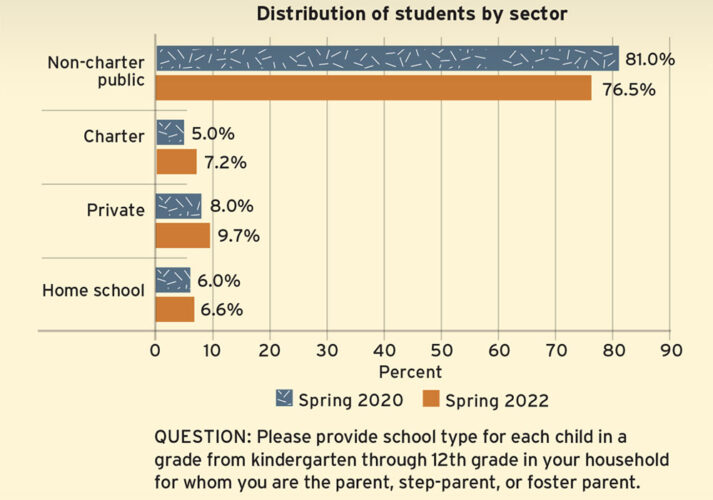

New data shared exclusively with The 74 suggests the challenges caused by a shrinking K-12 population won’t be ending anytime soon. Conducted by Tyton Partners, a consulting firm that examines pandemic-related shifts in education, the survey shows that between spring 2021 and spring 2022, there was a 9% drop in families saying their children are enrolled in traditional public schools — a plunge that translates into over 4 million students. Charters and private schools, meanwhile, saw increases in the survey, as did homeschooling.

The figures amount to a threefold increase over the drastic 3% decline K-12 schools saw two years ago. According to the U.S. Department of Education, that was the largest single-year drop since 1943.

Experts were quick to signal caution about Tyton’s numbers — parent surveys are not the same as official data — but said both are important for understanding the massive changes the K-12 system has weathered since March 2020.

“These are wakeup calls,” said Jenn Bell-Ellwanger, CEO of the Data Quality Campaign. “Is there something bigger happening here that we need to understand?”

The results, she said, should prompt district leaders to “interrogate” their own enrollment data, especially at key transition points like kindergarten and middle school. If families aren’t coming back, she said, officials should ask why.

States will begin posting official figures later this fall. A few, including Georgia, Louisiana and South Carolina, post enrollment more than once a year, but their spring 2022 counts show negligible changes — nowhere close to a 9% nosedive.

State figures don’t separate district and charter schools — all are public. But even when the Tyton researchers grouped both sectors together, there was still an 8% drop in parents saying their children were enrolled in a district school.

The researchers’ task “was to get a parent perspective as opposed to a policy perspective,” and to offer results that were more uniform across the country, said Nicholas Java, a director at Tyton.

Tyton works with organizations throughout the education sector, including nonprofits, corporations and major philanthropies like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation. Walton and Stand Together Trust, which support alternative models to traditional education, helped fund the parent survey. Tyton was also among the first to collect data on families’ use of pods and microschools.

Ultimately, most states are unlikely to see such dramatic declines. But trends in several large districts show that a nearly double-digit decrease over a short period of time isn’t far-fetched. Enrollment has fallen almost 10% in New York City schools since the beginning of the pandemic and dropped almost 6% in Los Angeles Unified last school year. The Chicago Public Schools is also expecting to lose more students and is on track to fall out of its spot as the nation’s third-largest district.

‘Data quality’

The Tyton survey of almost 3,100 K-12 parents reached a mixture of low-, middle- and high-income parents across the political spectrum. The results mirror recent trends in states like North Carolina, which has seen growth in homeschool and charter populations, and Arizona, where families are registering to take advantage of the state’s new universal voucher program.

Adam Newman, managing partner at Tyton, attributed most of the enrollment drop in the survey to “experiences parents had as a result of the pandemic, a desire or a sense that they needed to go someplace else.”

That’s the conclusion Deanna Sheaffer reached after watching her youngest son Rush fall behind — especially in language arts — during remote learning at Mark Twain Elementary School in Houston. Her experience reflects that of parents who responded to Tyton’s survey.

“Let me tell you what 10- and 11- year-olds do when they’re on Zoom — Grammarly,” Sheaffer said, referring to an app that corrects spelling and grammar. “He didn’t learn how to spell.”

The daughter of a former public school teacher, Sheaffer and her husband chose their neighborhood because of the quality of its public schools. But with three older boys, she knew Rush should have been getting a higher level of schoolwork in fourth and fifth grade. She didn’t want to take a chance with a district middle school and enrolled him this fall at Trafton Academy, a private school, for sixth grade.

It’s a trend districtwide, with enrollment this fall still well below pre-pandemic figures.

Thomas Dee, a Stanford University education professor who has been closely following enrollment trends, noted that Tyton’s sample of at least 3,000 “could give you nationally representative estimates.” But he warned that the survey’s design could introduce what researchers refer to as “noise” in the data.

He said, for example, that he’s “perennially surprised” by parents’ misunderstanding of charters, which could lead more to respond that their children are in private schools.

Confusion over remote learning could also impact some parents’ responses, added David Houston, a researcher at George Mason University in Virginia.

“At the height of the pandemic, what did homeschooling mean?” he asked.

Houston co-led Education Next’s recent parent survey, which also showed declines in parents saying their children attend district schools. But he said the authors downplayed those responses in their report because the enrollment question is “uniquely difficult to answer with surveys.”

Whatever discrepancies exist between survey results and more official enrollment data, no one questions that the K-12 system continues to confront an unprecedented loss of students — one that is forcing leaders to make tough decisions about staffing and class sizes. Speck, with School Services, said some California districts probably should have downsized years ago, but most aren’t talking about it.

“While districts know that they will need to contemplate staffing reductions and school closures now or in the future, the larger community is quick to focus on ‘How are we going to get kids back?’ Their constituents don’t want to talk about letting staff go and closing schools,” she said. “Under this kind of community pressure, it is difficult for district leaders and [school] boards to think about the long-term impacts of declining enrollment.”

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust supported the School Disrupted 2022 project at Tyton Partners and provide financial support to LA School Report’s parent company, The 74.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.