What’s the right goal for student achievement? Is 50% proficiency enough? 63%?

David Wakelyn | May 15, 2024

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

New York City districts with above-average reading scores have asked for flexibility from Chancellor David Banks’s new literacy curriculum mandates. This raises an important question for school leaders nationwide: What’s the right goal for student achievement? Is 50% of students reading and writing proficiently good enough? Is 63%? What is the right number?

Edwin Locke and Gary Latham are two scholars who’ve spent nearly 50 years studying goal setting. In the most comprehensive summary of their research, they advise organizations to set goals that are meaningful and “difficult but attainable.”

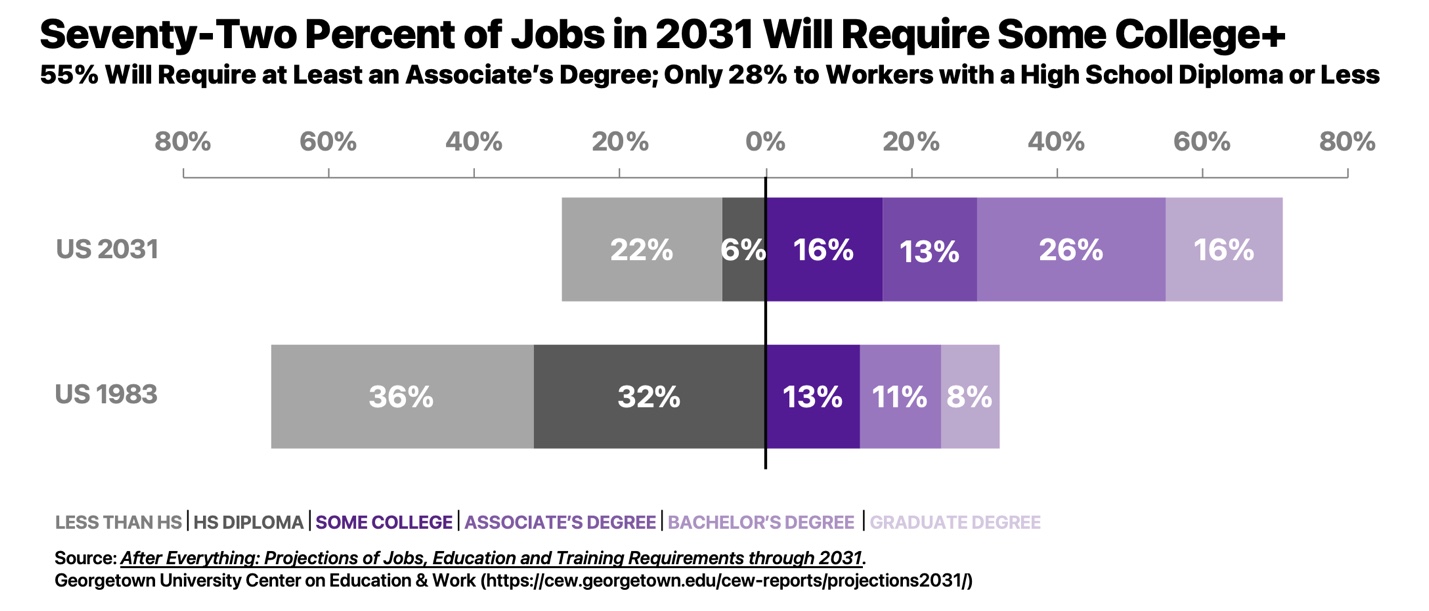

One meaningful purpose of schooling has been to prepare students for college and careers. Georgetown University economists project that by 2031, 72% of jobs in the United States will require at least some college, while 55% will seek applicants with an associate degree or more. This is the reverse of the educational requirements of 40 years ago, when 70% of jobs required a high school diploma or less.

New York’s Board of Regents has made multiple changes to standards and tests in the last decade, but there’s a general sense they remain aligned with college readiness expectations. State tests give parents and teachers a sense of whether students, all the way down to elementary school, are on track to being college-and career-ready.

With this system in place, it makes sense for New York City’s achievement goals to align with the proportion of students who will eventually need to be prepared to succeed in college over the next decade. In other words, the K-12 and higher education goals should match: Having 72% of K-12 students reading and writing proficiently, and a similar number on track to complete some college, is a meaningful goal for school leaders, teachers and parents.

One advantage is that this goal removes “we’re above average” as the aim, and it gives school districts a target that’s grounded in what the state’s future economy needs. It also applies the same goal for every group: low-income students, English learners, white students, etc. — all must reach 72% proficiency, the same high floor of excellence.

What might it take to get there?

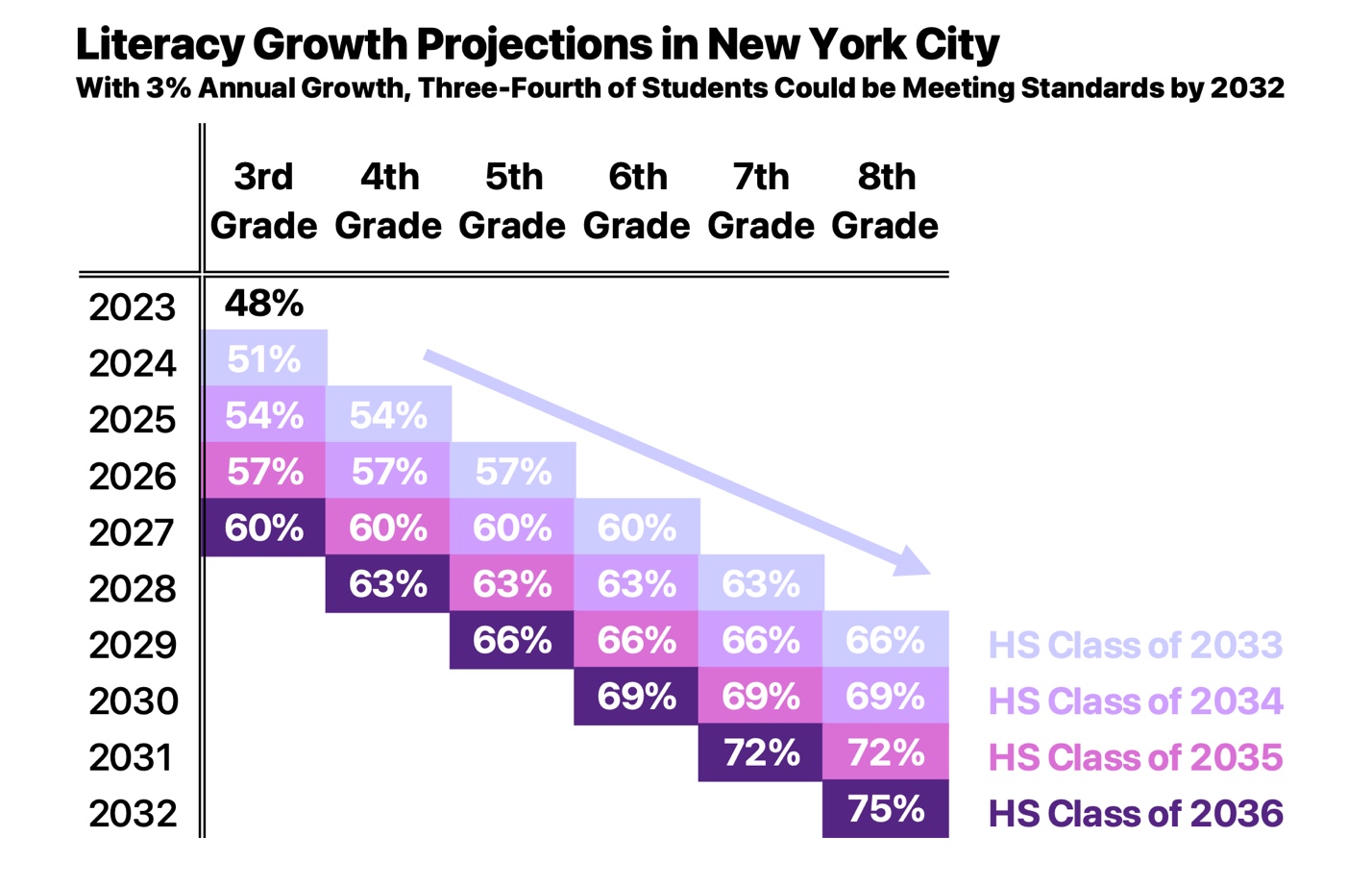

Last year, just 48% of New York City third-graders could read and write proficiently. Increasing that number by 3% a year, across each grade, could have 72% of eighth-graders meeting standards by 2031 and 75% by 2032.

Principals and teachers would need to follow classes of students as they move through school, something most reporting and accountability systems don’t currently do. The trajectory would look like this for each new class:

To reach that goal, each district would have to increase literacy achievement by 3% a year, not just among third-graders, but across every grade. Three percent fits the “difficult but attainable” criterion.

Why not set a goal of 100%? Isn’t it OK to be ambitious and aim high, even if districts miss?

No Child Left Behind famously asked schools to get 100% of students proficient by 2014. Not even the wealthiest districts in America managed to achieve the goal. Locke and Latham warn leaders that if a goal is set at a level no one can reach, it eventually undermines individual motivation and effort. People in an organization can easily become demoralized if they believe the goals set for them are unachievable. Better for district leaders to treat 72% as the floor for all and raise it once they have experience on what it takes to get there.

For districts whose communities insist on 100%, they might consider the approach the United Nations uses with its sustainability goals, which aim for Zero Hunger. In schools, this would mean getting to no students at “below standard” and all students scoring as “partially proficient” or higher.

Preparing students to be college and career ready is not the only goal of schooling, but it is one of the most important. As school leaders develop and refine their strategic plans, it’s crucial that they keep “meaningful and difficult but attainable” as the criterion.

Growing 3% a year feels do-able from classroom to classroom. It’s realistic, based on progress schools have made in the past. If New York City is consistent in its efforts, it will be one of the nation’s leaders in literacy achievement.

David Wakelyn is a partner at Upswing Labs. He was an education adviser to former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo.